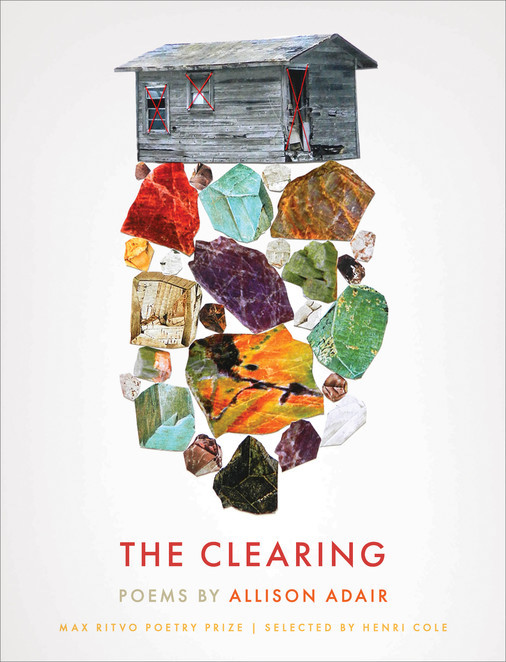

THE CLEARING

Allison Adair

Milkweed Editions, 2020

79 pages. $22, hardcover.

Allison Adair’s The Clearing opens with two words that haunt the book: “What if.” The title poem, which initiates the collection, imagines, through familiar fairy tale imagery, that our lives unfold as stories wrought with these what ifs.

What if this time instead of crumbs the girl drops

teeth, her own, what else does she have, and the prince

or woodcutter or brother or man musty with beard and

thick in the pants collects the teeth with a wide rustic hand…

The pieces are recognizable—pursued girl leaving a trail, some man of ill intent pursuing her: “we’ve got ourselves a familiar victim.” Some parts of the story can change, hence the “what if this time.” Some parts of the story are cemented:

It is written: the world’s fluids shall rush into a single birch

tree and there’s the girl, lying in a clearing we’ve never seen

but know is ours.

“We’ll write this story again and again,” Adair writes, and she does; so many poems of The Clearing testify to women who flee, who are pursued, haunted, lonely, regretful, or victim. The most significant tension threading this collection together is the tension of this first poem—how much of this narrative is pliable? Can we merely change out the scenery along the way, knowing we’ll end with the girl pecked clean in the clearing no matter what? Or is the narrative pliable enough for us to arrive somewhere else? Some of the poems lean toward a bleaker determinism; some toward the hope of the “what if.”

A handful of poems take place in Silverton, Colorado, a mining town nestled in the mountains. The town itself becomes a kind of “clearing” from the opening poem, an entrapment, a dead end. From “Silverton”:

It doesn’t matter who answers

the phone, it’s the same forecast:

snow following snow,

road closed followed by Jessie

returning to John, wrist healed

and you can hardly tell anything

went wrong, until she waves hello.

The “same forecast” on the other end of the phone, the glossed-over domestic violence, sounds the bleak note of the fixed narrative, the same story of the victimized woman, simply retold with a change of scenery. But it also suggests that we persuade ourselves into a kind of amnesia about the things we can’t face or change: “We forget why / we came—but look at that mountain. / Was anything ever so new?”

“As I Near Forty I Think of You Then” is a moving poem that picks up the wistful note of “what if.” In many of the poems the use of the second person point of view is reflexive, or if not reflexive, then the “you” is unspecified, but here it is the speaker’s mother. “And if your face were younger I’d buy you / the house you’ve always wanted,” Adair writes. The poem proceeds to list these desiderata, desires realized too late, and thus unmet—and in a moment of beautiful candor, the speaker says simply,

I’m sorry for what’s next. You, stranded

at a gas station in Ohio. Infant surgery and

the cast that followed. Years my father spent

quoting the Bible as you swept and stewed, saved,

let out hems. While we kicked and bickered

your thirties away. If I could go back to the dark

farming soil, I’d rip out the hyacinths and plant you

a lifetime of hydrangeas.

Adair’s gift for musical lines shines here: notice the alliterative “swept,” “stewed,” “saved,” not to mention the clever double use of the verb “stew” there, and “hems” suggesting the ghost of “hymns”; the internal rhyme of “kicked and bickered”; and her suggestive use of the line break in the last three lines. “If I could go back to the dark” hints a return to the womb—original dark—but the hope would be to “plant you”—to establish the mother anew, elsewhere, where she might grow and flourish into something wholly other.

Conceptually, “As I Near Forty” reminds me of “Angelus,” a persona poem that likewise picks up the notion of erasure, but through an art historical example. From the point of view of the woman in the painting, the poem tells of Jean-Francois Millet’s painting The Angelus, which was long presumed to show a couple praying over the coming harvest, their heads bent reverently over a basket at their feet in the field. But Salvador Dali insisted they were mourning the loss of a child, and as the epigraph to the poem tells us, “an x-ray revealed Millet had first painted a child’s coffin, then covered it over with a basket.” It would be easy, I think, to overwrite such a poem, or for the poem to fall short of the facts inspiring it, but Adair makes the brilliant choice to write it from the point of view of the painted woman, who addresses her dead child. In this way, it fits in with the cast of characters threaded through the collection, these two becoming another retelling of the fable. The poem opens:

Little mud shadow, hidden root,

only some of us know you were

here, ever a motion at all, a wave

before an arm, a seed just splitting

for the sprout.

Adair’s opening lines are so acute, especially the metaphorical use of “root” and “seed just splitting.” They show a way that both interpretations of the painting are right: the couple does pray over a harvest, so to speak, but it is a harvest of their bodies, and one they’ve already lost. In a surprising turn, the mother-speaker references the painter—“the painter understood / how to obscure”— collapsing the artificial wall that would separate “art” from life. I think the mother’s knowledge of the painter, and then of “Salvador, the man who bent time,” unites with the idea introduced in the title poem that narratives are not simply told by us or to us; we participate in their telling, even if we can’t wrench the outcome toward some other place. The mother in this poem is not just the painter’s subject; she is not passive. She is collaborative.

The poems of The Clearing form an intricate, compelling whole, sensual and musical, haunted (one poem literally featuring a ghost), and committed to focusing on what is often too blurry to see: the conflation of “longing” and “lure” for instance, and the difficulty of wresting forms of love from forms of violence. The collection closes with “Bear Fight in Rockaway,” a way of reversing the landscape of the opening poem. In “The Clearing,” the girl runs from house out into the wild, and in “Bear Fight,” the wild brings its danger right up to the house: “Then suddenly, bears: at the mailbox, / at the door.” But the occupants “are glad // to see them, old friends,” because their “patient combat” is familiar—

The way the bears’ bodies linger before they strike, mouths

open, slack—we remember something of that, from before

all the fences, the stairs and the cars, from a similar injury or kiss.

The final words—“injury or kiss”—do such justice to the obsessions of the collection. “The Clearing” is a wonderful, exhilarating debut, a book for any who want to live for a while in the realm of the inarticulable.