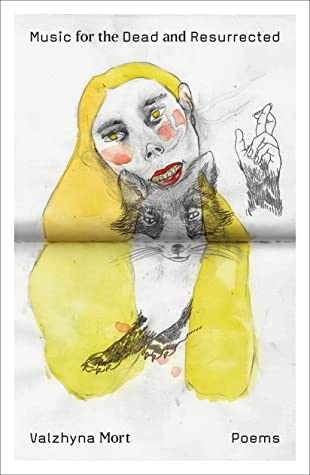

Valzhyna Mort

Music for the Dead and Resurrected.

2020. Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux.

$25, hardcover. 95 pages.

Reviewed by Chelsea Wagenaar.

Valzhyna Mort’s Music for the Dead and Resurrected is unlike anything else I can remember reading for a long time. The poems are at times quick and barbed, and at others achingly patient. They are rooted in Belarus, a beleaguered country shattered by WWII, Soviet control, and the Chernobyl fallout, and they voice those narratives, lives, and deeply haunted questions of identity. Mort’s images are startling, especially for the ways she combines the conventionally beautiful with the unaesthetic, even the gruesome, and the images recur in shape-shifting ways, looped through the poems in a manner true to the book’s organizing theme, music. Mort incorporates music in overt and covert ways. The titles announce musical forms—the book’s title and several individual poems, too: “Little Song,” “New Year in Vishnyowka (a lullaby),” “Psalm 18,” “Singer,” and “Music Practice,” to list a few. In my favorite near-title example, Mort includes tempo instructions as a kind of epigraph to the opening poem, “To Antigone, a Dispatch”:

allegro for shooing off the police

adagio for washing the body

scherzo for soft laughter and tears

rondo for covering the body with good earth

Many of the poems use music in details (an accordion player appears in several, and images like “piano-key coffins”) and in form, functioning like rondos, with phrases, images, and words repeating and altering throughout.

In “To Antigone, a Dispatch,” of the aforementioned tempo instructions, the speaker entreats Antigone, “pick me for a sister,” becoming an alternative to Ismene, the sister whom, in Sophocles’ play, Antigone sharply, swiftly renounces for not joining her in the forbidden work of burying their dead brother. Mort’s dark humor is on full display in the opening poem, as well as the defiant vitality of her voice.

I, too, love a proper funeral.

Drag, Dig and Sisters’ Pop-Up Burial.

Landlady,

I make the rounds of graves

keeping up

my family’s

top-notch properties.

The speaker has experience; she’s reciting her qualifications, her resume of burying the dead, which, in this Belarusian landscape, is practically an industry. But it’s an industry in which she takes great pride: “You can spot my graves from afar, / marble like newborn skin,” the simile suggesting this is her true mothering work, to lay the dead in their cradle of earth. Burial becomes an individual expression, a strange agency, and she has no time for the usual frills of domestic life, bickering “with husbands about dishes”—for there are “mountains of skulls to shine.”

The diction ranges in tone, moving from bluntness to eloquence in a line or two:

My guts have been emptied

like bellows

for the best sound.

Such an image would be made feeble by a word like “belly” or “body” in place of “guts.” “Guts” is the viscera, and the sonic brutality of the monosyllable is necessary to the credibility of the image. In the play Antigone, after Creon sentences Antigone to death and Ismene tries to accept the blame and punishment, too, Antigone fiercely rejects her: “I do not want love / from anyone who loves with speeches” (trans. Richard Emil Braun). Mort’s rewritten Ismene wouldn’t dare:

Pick me for a sister, Antigone.

In this suspicious land

I have a bright shovel of a face.

One of the most important poems in the book is “An Attempt at Genealogy.” The poem is in twelve numbered sections, and they proceed by asking, over and over, “Where am I from?” But their logical procession is not linear: it’s circular, as the sections loop back, pick up previous images, and reuse and revise them. Formally, this seems to render a truth about inheritance: that all inheritance, biological, cultural, linguistic, is by necessity an act of repetition rendered new each time. The speaker interrogates all manner of her origins, beginning with the theological, and section one introduces an image of religious iconography that is central to the poem:

In black basilicas

dragged incessantly

down a cross

is a man

who here resembles

a dress

snatched from a hanger

In section two, the image becomes

Yes, a man

resembles

a dress

snatched from a hanger.

Inside black

alphabet

dragged incessantly down

each letter

is a man.

In section four, it’s a parenthetical: “(again a man / resembles / a dress snatched from a hanger).” The phrasing of the image erases all agency—who snatched it? For what purpose? To be taken where? The image is simply of an aftermath. By beginning with the problem of religious identity, the poem suggests a lack of a satisfactory systematic theology, and this morphs into lack of any systematic sense of selfhood at all. Other images that repeat throughout the poem are a rotary phone (“A rotary phone is my gene pool…Blood is talking!”); household objects with faces (“the face of a clock, / the face of a radio on the wall—”); and, finally, graves and snow (“Under the moth-eaten snow / my motherland has good bones.”). The assortment of objects and images that coalesce to answer the question “where am I from?” may seem motley at first, but they represent some of the basic ways we orient ourselves: through connection and interaction with others who help constitute our sense of being, through heirlooms and objects that offer a continuous familial narrative, and through place. “An Attempt at Genealogy” is a poem in which all possible narratives of identity have been obliterated through a variety of political and ideological crises.

The poem ends at the grave, and I think this is the closest to an answer can come. Where am I from?

Braid your bones bravely.

Finger-comb your bones

into neat braids

in our woods, ravines, fields, swamps.

I am from the dead, the poem seems to say, which is also a way of saying, I cannot know where I am from. Satisfactory genealogical answers to the question are buried, and the image is one of mass graves. It renders the speaker herself as a ghost, haunted and haunting rather than living, bereft of the collective memory that would define her.