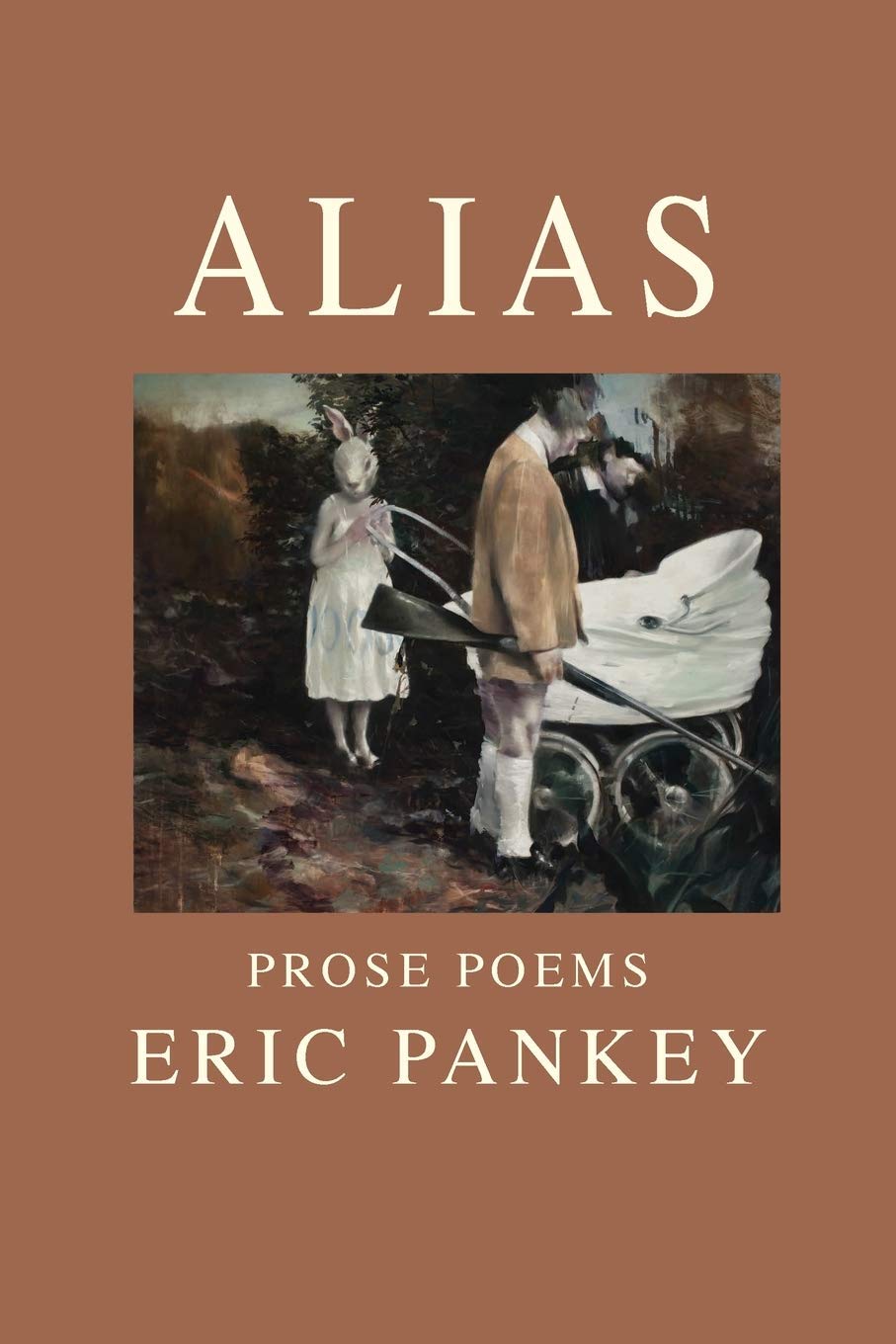

Alias

Eric Pankey

Free Verse Editions, Parlor Press

2020

Not to be confused with the television show of the same name, starring Jennifer Garner and beloved by Dwight Schrute, Alias is the second book of prose poems Eric Pankey has published with Free Verse Editions, by Parlor Press. One of the most crucial questions when reading such a volume is, what is a prose poem? And since that question has been nearly beaten to death, I’m going to skip it, in favor of what might be a more useful one: what is the prose poem allowing this poet to do? I’ve been reading Pankey now for over a decade—I’ve been haunted by his “My Mother Amid the Shades,” from Oracle Figures, among many of his other poems, all this time—and I think, compared to his last collections, the answer is room. It feels like there’s more room in this book—and by that I mean tonal range, but also more room for play, for whimsy, for delight, for memory, and for strangeness. There are still vestiges and themes of what we might call classic Pankey—the desire to identify patterns in the ordinary, to discover the divine, the need to consult the oracle bones, to throw the I-Ching hexagrams—and is there a poet alive, perhaps aside from Charles Wright—with a keener nose for the metaphysical?

These latter poems have, at times, been so spare, and sometimes so opaque, that I’ve felt locked outside them, even with multiple re-reads—though, to be fair, I’m probably a shallow thinker, as Wright also claimed to be once in a poem. And there are certainly poems like these in the book, such as “The Surveyor’s Map,” and “Et in Arcadia Ego.” And yet, after that decade of reading him, I don’t believe that there is any cleverness for the sake of cleverness—no cheap tricks, no showing off. Pankey is often a poet of the ardent, a seeker of truth, by turns a believer and a doubter, but his poems are never mere exercises in vanity. On the other hand, the room that I mentioned allows for poems like “Exercise in Intuition,” a poem I grappled with for a different reason: the extreme ranginess of its half dozen paragraphs. It seems to be a poem held together almost solely by the title—and perhaps by the idea that the epigraph introduces as well (“To render Time sensible is itself the task.”). The poem ranges from the past—apparently “archived on some obsolete technology”—to Delacroix, to Leonardo, to a question about nostalgia, to verdigris, to different names for Osage oranges. And perhaps the movement of this poem broke ground in the book for “By Another Route,” a long, multi-page poem at the heart of the collection, a heaven-haunted (or perhaps “next life-haunted” would be more accurate), time- & eternity-dogged poem, a penumbra where the uncanny and God meet, a spiritual pilgrimage wherein “One subtracts everything that is not God and finds a minus sign,” a poem dazzling in its historical twists and allusive turns: “Subtracted from the inventory: three thousand hand-carved ivory beads in a Cro-Magnon grave, a sieve to separate out prime numbers, the parabolic path of Holofernes’ blood splatter away from Judith’s blade, Heisenberg’s formal description of the relations among perceptions…”

But I’m glad to be challenged, as a reader and a poet, and the range and the room I mentioned earlier also allows for poems like “The Hyenas,” in which a pair of well-dressed hyenas show up at the door like missionaries…and proceed to speculate about the nature of art, and writing, ranging from Cage to Char to Bachelard, to Horace. The poem’s unusual narrative situation is funny in itself, but the way the hyenas leap from thought to thought is delightful—I hadn’t quite taken note, prior to this book, of Pankey’s Buñuel-like knack for the surreal, though there are small flourishes across the book, such as in “The Unexpected Return:” “Night spread wide across the island until a dispersing agent spilled from a crop duster. Then it was morning again with unexpected media coverage and roadwork ahead.” “Outtakes from The Newlywed Game” actually had me laughing out loud: “Regarding making whoopie, she compares it to an algorithm that collapses into randomness. He compares it to the water’s surface: fugitive, ethereal, a depth without reflection. She shakes her head no and says, you mean it is like a fog illumined from within, aglow yet opaque. Yeah, he says. What she said.” The lush lyricism and slightly absurd metaphors for lovemaking finish with a deadpan punchline that thumps the poem closed. “The Butcher” has undercurrent of this humor as well—it might fall under an “American Gothic” kind of portrait, one of a butcher who is married to a vegetarian and daydreams of an indoor swimming pool in Nebraska.

“Onlookers at the Scene” is another poem that has the feel of flash fiction, though in a more meditative voice, with a series of tangential thoughts from a plural first person POV that punctuate the scene—viewers watching a film, which Pankey uses to refract the narrative scene. These brooding ruminations on the nature of attention, and on the nature of perspective itself, is a mirror held up to the form of this prose poem, one that includes the extra dimensions of this nameless, mysterious film, within this scene: “We might as well be extras, onlookers at the scene, or mourners in Rogier van der Weyden’s “Descent from the Cross,” where the collapsed perspective engenders a feeling of unease. The space—illogical, cramped—holds more than it ought…” This might well be an ars poetica on the prose poem itself! I think it points as well to the slipperiness of subjective perception as well, which several poems are haunted by, such as “Not Good With Faces,” the title poem, and “About His Past Lives.”

It was also enjoyable to see some of Pankey’s influences at work in the collection. “The Late Shift” is dedicated to Mark Strand, and like some Strand poems, bears the fingerprints and loneliness of twilight into the world, and “A Story Coalescing,” a poem about a party, would not be out of place in Strand’s collection “A Blizzard of One,” in its offhand delivery, charming and speculative dialogue, and gentle humor. “Speed Dating,” too, has a funny and anticlimactic punchline from one character that follows a line of speculation from another character (“…what I am actually sensing in my peripheral vision is the gravity of interstellar gasses as they flare and contract…” // “Fair enough,” she says, “you’re a sensitive guy. But this genre usually begins with a question and not a confession.”)—a kind of “Sir this is a Wendy’s drive-thru” type of punchline—but one that reminded me of “I Will Love the Twenty-first Century.” “The Other Story About José” has the epigraph “after Carlos Drummond de Andrade,” and readers familiar with Strand will recall that several of his poems bore the same epigraph. This particular poem—with characters and narrative, and charged with what might be called A Curb Your Enthusiasm kind of humor (a senior manager at the “Office of Equity and Diversity Services” receives a complaint from a woman, and becomes infatuated with the complainant)—might well cross into flash fiction as well, depending on your definition of these genres. And that is certainly one of the pleasures of the collection—watching Pankey’s imagination stray across genres, or perhaps blur whatever boundaries one cares to draw to separate them.

I admired a number of other qualities in this book, but this little note at the end charmed me: “Many thanks to the graduate students over the years whose surprising writing prompts in my prose poetry seminar were the starting place for these poems.” A bit startling, isn’t it, for a poet of Pankey’s stature to admit—and certainly humbling for the rest of us. “Minor Arcana” and “Core Samples” could well be writing prompts in a creative writing class—not to mention “Outtakes” (e.g. have students come up with a list of events and/or cultural phenomena, then have them invent “Outtakes” for one or more)—along with “Catalogue Raisonné,” “The Mystery of the Ordinary,” and so many others—prose poem prompts that might follow or begin with the thematic or conceptual theme of each poem.

I often feel like I get to the end of a review without even scratching the surface of the book. I’ve not even mentioned the poems that begin in Greek mythology, the Biblical turns, the other turns into memory and strangeness—this book has many rooms! By turns meditative, philosophical, startling, moving, and funny, Alias is a luminous menagerie of strange and wonderful animals.