The Poetics of War: Three New Books on Armed Conflict and Armed Service

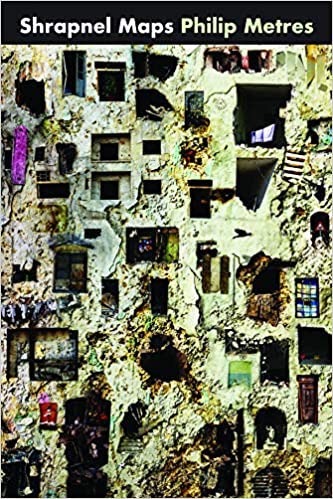

Shrapnel Maps

Philip Metres

Copper Canyon Press

2020

At the heart of Philip Metres’ new book, Shrapnel Maps, is a series of wide-ranging sequences, “A Concordance of Leaves,” “Theater of Operations,” “Poster (“Visit”) / Unto a Land I Will Show Thee,” and “Returning to Jaffa (for Nahida Halaby),” each of which grapples with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, in a wide-ranging series of forms and media, including ghazals, odes, sonnets and almost-sonnets/not-sonnets (ten to fourteen line poems and sections that feel like they’re kin to a sonnet), erasures, maps, postcards, guidebooks, quotes and allusions from holy books, photographs, even a “PowerPoint,” (“The Palestinian Refugee’s PowerPoint”), and a facsimile of a 1946 edict, “Instructions to the Arab Population,” from the British authorities. Metres, an Arab-American poet, offers a many-sided examination of a war that has now spanned generations, and though the concept of “witness” has become, for some, a loaded word, these are poems that bear testament—sometimes in almost a docu-poetic fashion— to the countless griefs this conflict, and the people therein, have inflicted and suffered. As the poet states in the Afterword, “Shrapnel Maps is my journey to clarify the question of belonging in a land with so many different names that to try to speak them all is to become crowded with history…”

Many of the poems take place in two locations simultaneously (one, “Three Books,” happens in three times and places at the same time—Metres calls it “A Simultaneity”), and to his credit, Metres refuses to simplify this conflict. In fact, one sequence, “Theater of Operations,” is stitched from twenty-one different first-person POVs, including a couple mourning their son, a suicide bomber, and one who feels called to clean it up: “Because someone has to pick up the pieces / of G-d. We get the call, & don neon vests // to sort the flesh from flesh.” As haunting as the details he includes, how much more so are the internal- and end rhymes and iambic pentameter—the poet imposing order and composing ironic music in the midst of chaos: “Here is a wedding hall. / Now scrape the bride & groom gently from the walls.” His locale (in Ohio) provides convenient symbols for the divide, including a tulip tree, and the offer of a ride from a stranger, in a poem that teleports from Ohio to a bus on Jerusalem, onto which a young Palestinian climbs, before being searched and arrested by soldiers. He also searches out his own complicity, and his unflinching honesty is both bracing and often profound—for example, in a poem within the “Unto a Land I Will Show Thee,” he remembers canvassing for Kerry—“promising his dogged support for Israel, knowing it could mean a wall between Ummi and olive trees she worries over like children.”

His unrelenting scrutiny extends beyond himself, of course, to the world around us, and the structures of power and history that hold up the institutions we’re often either too familiar with or apathetic to inspect ourselves. “Kafr Yar/ Babi Qasim” holds up an artifact, a book wrapped in the skin of a Native American—at a School of Theology, at a college “bought by the sale of Africans,” while quoting a prime minister and tracing the changing of place names: another erasure, in a book that is often a record of erasures, of a people, of a nation, and of cities: “Ayn Hawd became Ein Hod. / Nahlal arose in the place of Mahlul. / Ashdod in the place of Isdoud / Jaffa became Yafo.”

A sequence of poems, “When It Rains in Gaza,” is particularly moving, and begins with—and plays with—surreality in a fashion unlike the rest of the book: “I’m not there or here / when she presses the book // to her chest, pauses to eye us, / then disappears inside the pages.” Two sections later, the reader finds Rahed Taysir al-Hom inside a bomb. Why the move to the surreal? It’s one way, I think, to process the often mind-numbing details in this first-hand depiction of a post-war landscape—no, a landscape of an ongoing war: The bombing of an ice-cream factory. Tunnels dug in the dark beneath a sky aswarm with surveillance drones. “Eighty-five percent of West Bank water is funneled into the settlements or into Israel.” The tenth section, “Future Anterior,” is a Q & A that asks a series of questions that are both basic and unanswerable (“What is a ruin?”), and traces language itself, its errors and evolution: “She slid / into a comma / she was driven // by ambulance / dashes to ashes / pupils to colons / the new revised standard // replacing the old revised standard / replacing the King’s version…” So what knows no walls? A bullet: “The lower the bullet hole in the water tank, the less the family can drink.” The sequence finishes with poems dedicated to the Israeli poet, Yehuda Amichai, and the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, followed by other poets, and in this way the book is also a bridge between the two peoples, one that seeks to cover the distance between them with the utterance of poems. And though there are poems with lines that sprawl across the page, and though there are allusions and quotes that give some pages of the book the look or feeling of a palimpsest or pentimento, Metres’ lines are often measured and spare, as in the twenty-six part “A Concordance of Leaves”—the Arabic word for “leaf” at the top of every page, in ten sometimes-rhymed couplets in rough iambic pentameter, tetrameter, and trimeter: “because there is a word for love in this tongue / that entwines two people as one…” But in both modes he is concerned with finding the humanity of each person, whether in Ohio or in the Middle East: “Yehuda, I want your clarity— / to love you, not close the gates // of my heart like a nation…”

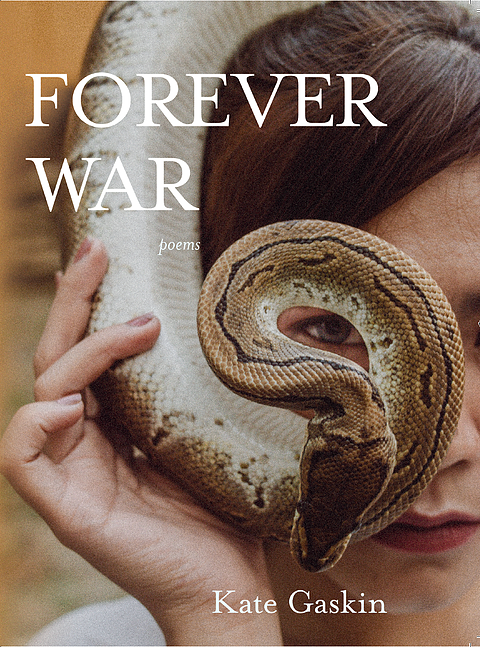

Forever War

Kate Gaskin

YesYes Books

2020

Forever War chronicles the experiences of a soldier’s wife across the months and years of repeated deployments, and the weight of the deployed spouse’s absence. It also marks out a lineage as well—the speaker’s father is a Vietnam War veteran, and the book moves, through four sections, from one deployment, into another, back into tracing the scars and trauma of the Vietnam War, and on into the final section, “Forever War.” The speaker and her family bear the brunt of America’s wars, while those around her seem largely oblivious to the sacrifices she and her family make. The first section, in particular, describes one of those sacrifices, that of rearing an infant by herself. In “Postpartum” the speaker dissolves an image of their son turning over into an image of the father at war: “He is rolling over / front to back, back to front, // as you crouch / in the desert and cradle / your phone.” The infant both magnifies the speaker’s aloneness, and has, of course, plenty of demands of his own. “Permanent Change of Station” also details this life as well, and Gaskin’s choice of form, a pantoum, is judicious here—a pantoum is a form in which two lines of one quatrain repeat themselves in the following quatrain, and its very structure enacts the cycle of her spouse’s departures.

Aside from examining the suffering—and guilt—that war causes, her poems share another kinship with Metres’: her poems are often split geographically between two places, the speaker’s Alabama landscape, and the foreign cities and countries where her husband is deployed. And as with Metres, she too does not shrink from her own complicity in the war—in “Forever War,” the speaker interrogates her own role, and believes that “I am no better / with no finger on a trigger / than any other colonizer,” while in “Delta, Echo, Alpha, Romeo,” she asks “Tell me / then, how you loaded / the bombs, how you parted / the air, how the ocean divides/ breath between us…Not once have I believed we’ll be spared.” The opening of the poem is characteristic, too, of her spare two to four beat lines, and the music she is capable of: “January, Omaha splitting / open like a wound, like a moan / hard with teeth, back when // we spoke on the phone delta, echo / alpha, romeo…” The long assonance of the o-sounds and the internal rhymes between Om, open, wound, moan, phone, skillfully deepen the wound she’s describing—which, if you’ve been in a Midwest city in the dead of January, you can probably still feel in your bones!—and the solitude of the speaker as well, and the military call signs further estrange the domestic sphere, and speak to both the geographic distance as well as the vocational distance between the couple.

That distance is characteristic of many of the poems in the book, yet Gaskin casts a wide net, and Forever War does not get repetitive. “Elegy with Whale Fluke and C-130s” mines an ecological vein, juxtaposing the speaker’s concern for her family with worry for the whales, even in a time of war: “and yet // I order my time by listing / all I have to lose: child, bread, water / and whales, which are dying again / warming oceans emptying // of everything good as C-130s split / the sky above…”, as does “Monarch Season,” in which the migration of monarchs becomes an extended metaphor for the movement of the speaker’s husband: “the air thick with their longing / to be anywhere but here.” Another elegy—there are half a dozen throughout the book, another thematic and structural thread—“Elegy with Citrus Greening and a 100-Year Flood” pairs an enjambed syntax with anaphora and a series of images from the natural world to explore mortality and beauty. “Ghazal for Alabama” offers a brief but troubling history of the state—though finishing on a hopeful note, the speaker being embraced by her beloved—while “Black Hawk” spells out the dangers of vertigo, and the sequence “Vietnam War”, while reporting the various manifestations of PTSD in a former soldier, also studies the natural world for hints into the future as well, a kind of divination that follows the appearance of what the speaker believes is a premonition, “A field shorn for winter, a hundred // fawn-colored bucks / throats slit and blackening the grass.” The sequence also asks a question that is central to the book: “Why are there only / two wars in this book / there is never not a war // somewhere the one / we were born into and / the legacy we’ll leave our son…”

“Fuck, Marry, Kill” is an absolute riot of a poem—a game in which a player chooses three people for the aforementioned fates—and the speaker, in an email to her husband, chooses Marlon Brando and Paul Newman for the first two, in lines that are strewn with lively rhymes. And yet the humor and the heat is placed alongside the speaker’s loneliness (“There are months when no one / touches me, months //of snow…”), the distance between the two, the sobering news of the day, and the speaker’s awareness—or best guess—of what’s happening in the theater of war: “On the news / another woman explodes // in a crowded marketplace. Snipers go panther- / still behind their scopes.” What a wide tonal spectrum! Humor, games—one more way of getting through the day. Unless you’re Cary Grant, unfortunately: “…I’m lonely and I’m young / and this version of Cary Grant is done / for. When you finally come home, the thaw slings up the tulips one by one.”

I have to admit I resisted the instances in which the heart is a winged thing, but Gaskin offers plenty of imaginative similes to estrange the aortic landscape, as in “Vietnam War,” in which it is “always tearing / away from itself / like a horse broken loose in a storm.” And in the aforementioned “Delta, Echo, Alpha, Romeo” she imagines “…all the tiny wicks / of dread curling their small // fires deep into my heart.” And there are many other examples of inventive figurative language that complicate her poems aside from the interior landscape, as in “The Exotics”: “What was it you said / when the throng of gulls / flocked to us like bed sheets // flung and pillowing…” Or “Pennies”: “where all that summer / we porch-sat and wished // on empties that glittered / the ditch across the street / as if they were pennies in a well.” I wanted to conclude with her use of figurative language, because comparing the heart to a variety of things is risky, and points, I believe, to a kind of courage and a kind of ambition, that of a poet who is willing to take a chance to move her readers emotionally—especially in an age in which so many poems feel like mere language games. “Forever War” is a remarkable debut book of poetry from a young poet with a bright future.

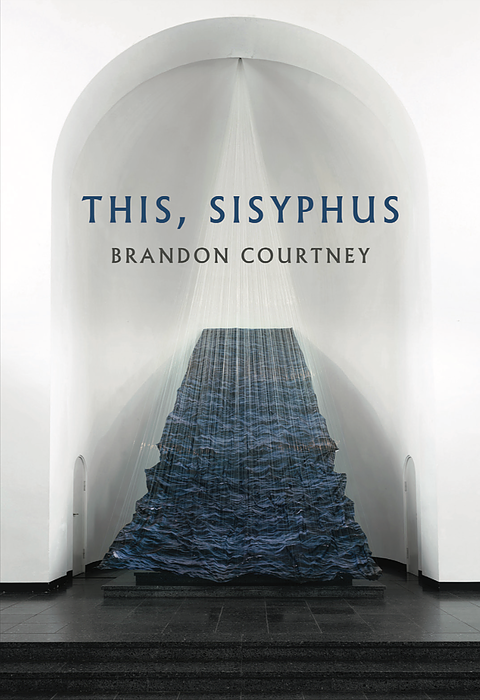

This, Sisyphus

Brandon Courtney

YesYes Books

2020

A familiar plot trope on TV and in films is the police sketch, where the face of a suspect slowly comes into view. One of the most haunting aspects of Brandon Courtney’s This, Sisyphus is a series of poems that directly address a “Ben”—and like a sketch or a developing photograph, the details of his life and death slowly become distinguished, but only little-by-little, and only after reading the poems addressed to him, which, because they appear at irregular intervals, knock the reader off-balance each time he or she encounters the address. Other poems use apostrophe as well, but in these other instances, it’s the speaker addressing the Lord—of whom, and to whom, the speaker sometimes confesses his doubt, even doubting His existence—and so the book sometimes has the spirit of Hopkins’ “terrible sonnets” (“Christ, like a season, you end where I begin: / make me harbor, so the ocean can erase me; / make what remains of my body a fist, a dust so small / even the thought of it might scatter me. Scatter me.”), or notes of the Psalmist in his lowest spirits, but in the passages that address or memorialize Ben, it was Tennyson’s “In Memoriam” that came to mind, in the way that Courtney also marries theological speculation with pronouncements upon life, alongside moments of Ben’s life and speculation about his death, and, finally, the details of his burial. Eventually, by “Comfort for the Infinite,” the reader comes to realize that the poet is elegizing a lover, and is searching the world, and everything in the world, to reckon with—and describe—the loss.

This search is relentless. In that poem, the speaker urges Ben to “Meet me where our love / first gathered, weightless / as a ring of hair spiraling / Jupiter: a sugar spun and sheer, / a bandage come undone.” These few lines are characteristic of Courtney’s work—a tight weaving of figurative language, imagery, and sound. I count a half dozen “r” rhymes, and a simile followed by two metaphors. The speaker often asks the impossible of his dead lover—“carve an hour from the empty air,” “Make it so you’re not a slouched / grotto of bones below / the frigid ground in Buffalo.” Courtney’s ear and his formal dexterity allow him to heighten music for ironic ends, as Metres and Gaskin do, and often times the full end- or internal rhymes close the poem with an audible click (sometimes even small thoughts or asides are closed this way, as Dickinson often did, or Kay Ryan, or A.E. Stallings: “Your love is an abode, / I know, an abacus / logic of yes or no.”)—yet there were times when the rhyme and consonance was so urgent, the figurative language so strange and dreamy, the speaker so needful, and yet the meter so precise, that the poem seemed to be simultaneously circling the world and zeroing in on grief—and sometimes it seemed like all the speaker could do was wring music from the loss, as if that were the only possible way to grieve.

And to do that without seeming melodramatic! I still don’t quite know how Courtney accomplishes it, aside from the craftsmanship of his forms, and the originality of his metaphors—his iambic trimeter and tetrameter in “Keel,” for example, seems effortless, and the speech so natural, that I found myself reading a section for the first time without grasping the form. Certainly the reader experiences this craft and invention in the received forms of some of these poems, as in the villanelle “Testimony,” or in “Wooden Star,” a haunting pantoum, or “Antichrist,” a triptyched triolet (with the order of the last two lines of each section inverted from the traditional form), but the poems are also rich in imagery along the way, and swell and recede in music, much like the (almost) ever-present sea. Yet beyond traditional forms, Courtney has an instinct for the movement of a poem, so that there aren’t poems that feel contrived—the sonnet that is a sonnet for no real reason, for example. On the other hand, the “Hexaemera” sequence uses, according to the end notes, “the structure of a traditional hexaemera, or the six days of creation (Greek 6 + hemera = day), first written by St. Basil in the 4th century AD.” In Courtney’s hands, the sequence moves like a sonnet crown, one in which the speaker converses with the Lord, while wandering through cosmological and eschatological questions.

With notable exceptions, this is a theologically impoverished period of American poetry. The end notes offer a window onto the pile beside Courtney’s reading chair: “Swedenborg, Bart Ehrman, Rudolf Otto, Old Testament pseudepigrapha [“pseude-what?”—poor Wagenaar thought at first that’s what Walter White used to make blue meth], Immanuel Kant, Alfred North Whitehead, Henri Bergson, St. Thomas Aquinas, and St. Augustine.” And yet the sophisticated observations, and the relentless questioning of the Lord, not to mention the eschatological speculation, leads me to conclude that Courtney wrestled with these texts with the same intensity as he grapples with the Angel of the Lord. “Drowning Stains the Ocean Gray” is both confession and accusation: “And I need / so badly to believe / that you’re my God and you reside / in everything: the multiverse and empty space, / down to every carapace, / parasites that nurse in dust… he did for me / what you never will, what you never can: he drowned, / which means he once was real; he touched / the gulf and every whitecap kneeled.” Section XI of “Keel” has the speaker ask the Lord: “Sing me, Lord, flutter, capo, / and strum. Not hush or salvo. Know me/ as the parasite I’ve become: host me / in heaven’s wool; let me slumber, rejoice / in puddles of your blood.” The pun on host is daring, I think, and “heaven’s wool” is funny, too, bringing to mind of course the Lamb of God, while offering some semblance of comfort—a rhyme-rich punning pleading with God that elbows blasphemy’s ribs, and feels authentic here, feels like a Courtney poem—this pleading, in music, with jokes, with a deity you sometimes don’t believe in and yet long to believe in—is certainly timely today for us living in an apocalypse, but when in human history has that pleading not been timely?