Danny Lawless’s generous invitation for a Romanian presence in Plume placed in an awful embarras de choix: there is so much wonderful poetry written today in Romanian, that I am obviously unfair to many other superlative Romanian poets with this narrow selection.

But then the reader is kindly asked to take this selection not as canon – but as a sample. I can assure her or him in all good heart that, for each poet found likable, there are at least other four just as good in Romania, waiting to be discovered on the Internet. This is a teaser of Romanian poetry – and should work as such.

I have selected a few of the best poets who have started writing (or at least publishing) immediately after 2000; I wanted them to be all very good (which they are) & completely individuated and differentiated (and indeed no two of them write alike). Andrei Codrescu, whom we all admire, is the guest star – I think both American and Romanian literatures are lucky to boast such a guest star, as a matter of fact.

As for the general characterization of contemporary Romanian poetry – in order to avoid any presumptuousness, I think it is better to leave somebody exterior to our Romanian culture to do it. And I find no better words than those of Ilya Kaminsky, taken from a review of Martin Woodside’a anthology of contemporary Romanian poetry (Of Gentle Wolves, 2011) – I’ll leave Kaminsky’s exact & insightful phrase to close this short intro:

“The Romanians included in this book are able to retain a sense of spiritual urgency in their work. This seems particularly relevant, I believe, for the North American reader. Today in the United States we seem to have no shortage of innovation–new styles are tried and re-tried by the day, even by the hour, and our poets prize highly the ability to do something else, ‘something new.’ But I wonder if we misunderstood Pound, and took his proposal to ‘make it new’ too narrowly. What one sees in North American poetry is a lot of ‘new’ material that is utterly boring, lifeless, much stylistic variation with very little soul involved, very little at stake. The ‘new’ Pound wanted us to deliver was ‘fresh.’ Much of what is delivered, however, is like engineering: curious structures, but no color, no senses. This does not have to be the case, and contemporary Romanian poets are an excellent example in how to avoid such a shortcoming.”

–Radu Vancu

Elena Vlădăreanu

(b. 1981; poet, prose writer, playwright, journalist. Founder of the Sofia Nădejde Prizes for Literature written by Women.)

from Bani. Muncă. Timp liber (Money. Work. Free Time), Nemira, 2017

I haven’t always weighed 62 kilos. But even when I weighed 48 I still

looked as if I weighed 60 or more.

Broad hips, large breasts, big bones. Drooping shoulders, like

my mom’s.

When I had barely got to know my present husband and I was very much

in love, he took a photo while I was making fries for him. I look like a housewife, I said, like an aunty. Delete it. I’m not deleting it. Isn’t that what you are? he answered.

I was.

But artists are not that. It didn’t go down well with me.

One day, a poet took his clothes off while he was reading his texts.

The thing went viral.

For a few hours, the favourite word on the net was:

Ding-a-ling.

Ding-a-ling!

Let’s say it together: Ding-a-ling!

Along with naked poetry.

A handsome young white heterosexual man. A pureblood artist.

But what if:

A not so young woman, with spare tires, sagging breasts, cellulite

Two children hanging onto her

Etc.

Etc.

performed naked poetry?

Oh, really?!

I like colourful clothes, artists dress in black. All black.

I don’t smoke, artists smoke. I don’t take drugs, I don’t drink.

Artists… well, never mind.

I’ve set my mind on losing weight. No more sweets and fat, start swimming,

jog in the park.

What if I also had a nose job?

Bought a back brace, back straight, shoulders up.

Radical wardrobe change.

I’m a raven.

Breast reduction surgery.

Artists are androgynous, I have REPRODUCTION written all over me.

The salvation of the species.

Housewife.

Mother.

Short, broad hips, fat thighs, spare tires, breasts, drooping shoulders.

Artists don’t reproduce.

Manole flies off the roof, his wife is walled up alive,

no offspring.

(trad. Andreea Hadâmbu)

Nu întotdeauna am avut 62 de kg. Dar şi când aveam 48 tot de şaizecişi arătam.

Lată în şolduri, sâni mari, oase mari. Umeri căzuţi, ca ai maică-mii.

Când abia îl cunoscusem pe actualul meu soţ şi eram foarte îndrăgostită, mi-a făcut într-o zi o poză în timp ce îi pregăteam cartofii prăjiţi. Arăt ca o gospodină, i-am spus, ca o tanti. Şterge-o. Nu o şterg. Ce, nu eşti? a răspuns el.

Eram.

Dar artiştii nu sunt. Şi nu mi-a picat deloc bine.

Într-o zi, un poet s-a dezbrăcat în timp ce-şi citea textele.

Gestul lui a devenit viral.

Pentru câteva ore, cuvântul preferat în reţea a fost:

Ştro-me-leag.

Ştro-me-leag!

Să silabisim împreună: ştro-me-leag!

alături de naked poetry.

Un bărbat alb, tânăr, frumos, heterosexual. Artist pur sânge.

Dar dacă:

Femeie nu chiar atât de tânără, burtă, sâni lăsaţi, celulită

doi copii atârnaţi de ea

Etc

Etc

practicând naked poetry?

Pe bune?!

Mie îmi plac hainele colorate, artiştii se îmbracă în negru. All black. Eu nu fumez, artiştii

fumează. Nu mă droghez, nu beau. Artiştii… în fine.

Mi-am propus să slăbesc. Scos dulciuri, grăsimi, început înot, alergat în parc.

Dacă aş încerca şi o rinoplastie?

Cumpărat o orteză, spate drept, umeri drepţi.

Schimbat radical garderoba.

Sunt un corb.

O operaţie de micşorare a sânilor.

Artiştii sunt androgini, pe mine scrie mare REPRODUCERE.

Salvarea speciei.

Gospodină.

Mamă.

Mică, şolduri mari, pulpe, colăcei, sâni, umeri lăsaţi.

Artiştii nu se reproduc.

Manole zboară de pe acoperiş, nevastă-sa-i zidită de vie, nici un urmaş.

Claudiu Komartin

(b. 1983; poet, translator, editor, and essayist. Editor-in-chief of Poesis internațional. Founder of the influential reading club The Blecher Institute. Runs the publishing house Max Blecher, specialized in poetry.)

19 martie 2022

Și ea care se pregătea să dea naștere copilului pe care și-l dorise ani întregi, cu ardoarea care numai mamelor li se dă, făcându-le să simtă în fiecare părticică a trupului greutatea luminii, grația ei posesivă și răbdătoare.

Și el care își strângea distrat partiturile înainte de a porni spre lecția de vinerea după-amiaza, iar micuțul Oleksiy îl aștepta cu un origami în formă de lebădă așezat pe tăblia pianului („singur am făcut-o, unchiule, așa e că azi mă vei învăța un cântec frumos pentru lebăda mea visătoare?”).

Și ei care se țineau în brațe când a căzut bomba.

Voiau doar lucruri simple, umane.

Voiau să trăiască, să cânte, să fie iubiți.

Cum poți privi în ochi întunericul fără să-nnebunești? Cum poți asculta sirenele de șase ori într-o zi fără să-ți smulgi auzul și să-l arunci cât colo ca pe o cărămidă? Cum să nu vrei în asemenea vremuri să aparții altei specii?

Ce caută grămăjoara asta de zdrențe însângerate pe marginea drumului și cum să accepți că e o mamă tânără târâtă dintre dărâmături, că aia este mâna micuțului Oleksyi, care-i adora pe Bowie și pe Chopin și care nu va mai face niciodată un origami?

Cum să explici distrugerea sistematică, îngenuncherea celui care încearcă să se emancipeze și să înalțe drapelul vieții peste toată abjecția și ura impenitentă?

În numai câteva zile.

Să numești oroarea poate că e cel mai dificil lucru, însă cât de monstruos e ca doar ea să-ți mai fi rămas?

March 19, 2022

And her who was preparing to give birth to the child she had waited for years, with the ardor that only mothers are given, making them feel in every part of the body the weight of light, its possessive and patient grace.

And him, too, who was amusedly gathering his scores before heading to Friday afternoon’s lesson, and little Oleksiy was waiting for him with a swan-shaped origami on the piano (“I did it myself, Uncle, so today will you teach me a beautiful song for my dreamy swan?”).

And them who were holding each other when the bomb fell.

They just wanted simple, human things.

They wanted to live, to play, to be loved.

How can you look into the dark without going crazy? How can you listen to the sirens six times a day without snatching your hearing and throwing it away like a brick? How can you not want to belong to another species in such times?

What is this pile of bloody rags on the side of the road, and how can you accept that it’s a young mother who was dragged from the rubble, that that’s the hand of little Oleksyi, who loves Bowie and Chopin and will never make an origami again?

How to explain the systematic destruction, the kneeling of the one who tries to emancipate himself and raises the flag of life over all the nonsense and unrepentant hatred?

In just a few days.

To name the horror may be the hardest burden to bear, but how monstrous can it be when this is the last thing that you still possess in this world?

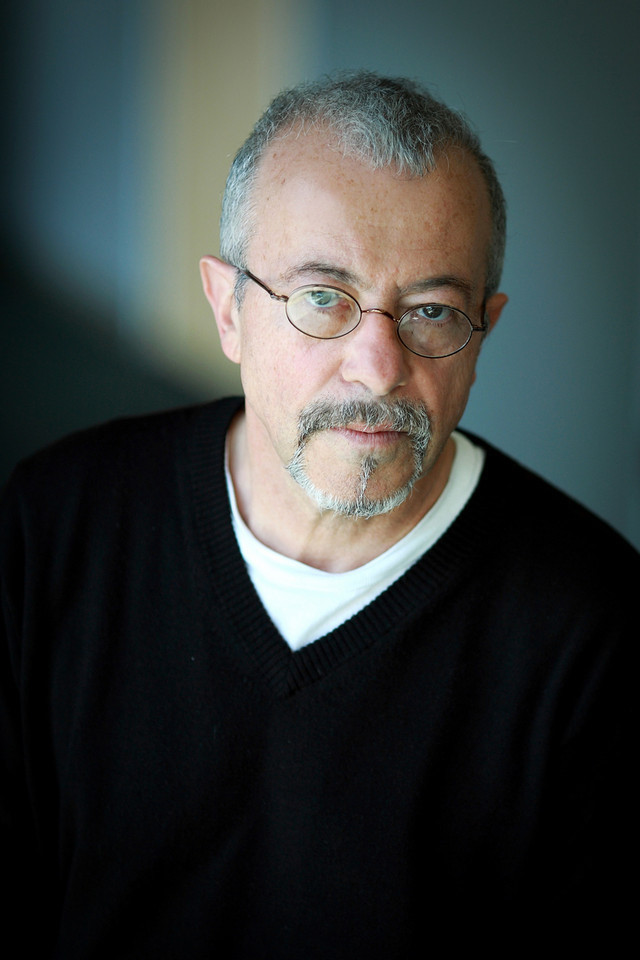

Andrei Codrescu

(b. 1946; Romanian-born American poet, novelist, essayist, screenwriter. His Romanian poems, written intermitently during a span of more than 50 years, have been collected recently in a massive volume called Visul diacritic.)

Căutăm Evreu

For Lidia Vianu

Pentru Lidia Vianu

I look deep

Mă uit în adânc

I look deep inside

Ma uit adânc în interior

I look sideways

Privesc împrejur

Mă uit departe la stânga

I look far to the left

Mă uit departe la dreapta

I look far to the right

within without all around

mă uit în mine afară peste tot

360 degrees around one mile within a thousand versts back to siberia

360 de grade un orizont de un kilometru o mie de verste până-n siberia

six inches to the topknot of the noose around my neck

șase centimetri de la nodul lanțului la gâtul meu

one third of an inch from the suppurating wound of my bunkmate

câțiva milimetri de la rana supurânda a tovarășului meu de pat

four inches from the laptop screeen

patru centimetri de la ecranul laptopului

five hundred miles to my cave

cinci sute de mile până la peștera mea

un milion de ani la atelierul paleolitic

a million years to the paleolithic studio

bizonul meu prinde contur

și constiința umană sare

un milion de ani către viitor

my bison is taking shape consciousness is taking

a leap a million years into the future

I look into the future until I’m tinier than nothing

Mă uit în viitor și-s mai mic decât nimic

I look into the distant past where I am nothing

Mă uit în trecutul îndepărtat și sunt încă mai nimic

and my mother and father are nothing

tata și mama sunt și ei tot nimic

and my grandmother and grandfather and my ancestors

iar bunica și bunicul și strămoșii mei

don’t exist yet for thousands of years

mai au mii de ani până să se nască

I look into the middle past where they still don’t exist

Ma uit în trecutul de mijloc și ei tot nu sunt

I look into the closer middlepast and still see nobody

Mă uit cinci mii de mile în adâncime

I look five thousand miles deep

La cinci mii de ani depărtare și văd

Nu văd nimic dar îmi închipui că-l văd

Pe don quijote pe catâr văd literatura

five thousand years distant and I see

I see nothing I am only imagining that I see something

I see don quixote on his mule I see literature

I see my bison in a museum

Îmi văd bizonul la muzeu

I drew that I say to the seventeen year-old girl

Eu l-am desenat îi spun fetei de șaptesprezece ani

Care era nimic când s-a ridicat muzeul acum cincizeci de ani

who was nothing when this museum was built fifty years ago

I look deep within and I see a seed

Mă uit adânc înăuntru văd o sămânță

E israel e evreul e sămânța de muștar

it’s israel it’s the jew I am israel a mustard seed

Am născocit totul de fapt nu e israel

I just made that up it’s not israel

it’s a dull round brown polished chestnut

e o castană rotundă cafenie și catifelată

or the button of a uniform

sau un nasture de la o uniformă

tot nu văd niciun evreu

I still don’t see any jewish person

Mă uit la distanța de trotsky la stânga

Mă uit la distanța de hitler la dreapta

I look trotsky-deep to the left

I look hitler-deep to the right

I look g-d high and joshua in the sky

Mă uit la înălțime de d-zeu și de iosua în cer

I still don’t see any jew where am I

Tot nu văd niciun evreu oare unde mă aflu

I don’t see any jew I don’t see me

Nu văd niciun evreu și nu mă văd nici pe mine

I look and look I feel something I see nothing

Mă uit și mă uit simt ceva dar nu văd nimic

it’s my mother calling me in for dinner

e mama mă cheamă la masă

I feel better thank you for asking

Mă simt mai bine mulțam de întrebare

28 aprilie, 2006

mid-air between New Orleans and Detroit on Northwest Airlines

în avion între New Orleans și Detroit cu Northwest Airlines

Read at the Sibiu Poetry Festival in May 2006

Citit la Festivalul de poezie Sibiu în mai 2006

Dan Coman

(b. 1975; poet, novelist, editor. Has also started collaborating recently with theatre directors. Organizer of the Poezia e la Bistrița Poetry Festival.)

NOILE DIMINEȚI

de cîteva ori pe săptămînă sunt nişte dimineţi noi

dimineţi care seamănă bine de tot cu oricare altele

doar că nu depăşesc un metru înălţime

un fel de cuburi educative pentru copiii de pînă la un an

aici nu mai încape cafeaua

tutunul nu mai iese din gură iar

dragostea noastră stă ca o vacă-ntre noi

şi ne umple de păr

pe aici se plimbă fiică-mea

şi pe aici plimbă ea tot soiul de corpuleţe

pentru care aerul e doar o jucărie de băgat iute-iute în nas

acestea sunt dimineţile noi

şi de-a lungul lor se rostogoleşte laptele praf

şi de-a latul lor ticăie neîncetat soarele chicco

acestea sunt dimineţile noi

la un metru deasupra lor

trupurile noastre mari plutesc deja cu burţile-n sus

THE NEW MORNINGS

several times a week there are new mornings

mornings that seem as good as any other

if they don’t quite reach a meter’s height

some educational cubes for children under one

coffee no longer fits in

tobacco no longer leaves the mouth and

our love sits close between us like a cow

shedding its hair

my little daughter walks here

walks all sorts of small bodies

for whom the air is just a toy

to push quickly-quickly in the nose

these are new mornings

powdered milk rolls all over the length of them

a chicco sun ticks endlessy over their width

these are new mornings

a meter above them

our large bodies float already belly-up.

Translated by Martin Woodside and Ioana Ieronim

Domnica Drumea

(b. 1979; poet and translator. Former member of the first significant post-2000 poetry movement in Romania, Fracturi.)

Creatură hibridă

lucrurile frumoase mă distrug

sunt mult mai bătrână decât tine

creatura hibridă căreia îi e mereu foame

am lăsat în urmă o casă sub asediu

nevoia mea de a mă crucifica

de a atinge orice mână întinsă

îţi cerşesc mila

deşi între noi nu există milă

doar un glob fosforescent care ne luminează

pe dinăuntru

în lumina zilei mă dezintegrez

creatură hibridă fără inimă

şi fără sex

am o soră geamănă

ea râde şi pentru mine

Hybrid creature

beautiful things destroy me

I am much older than you

hybrid creature always hungry

I’ve left behind a house under siege

my need to crucify myself

to touch any hand that reaches out

I beg for your mercy

though there is no mercy between us

only a phosphorescent globe shedding light

inside us

in the light of day I disintegrate

hybrid creature without heart

and without sex

I have a twin sister

she laughs my share of laughs too

Translated by Anca Bărbulescu

Ruxandra Novac

(b. 1980; poet. Former member of the first significant post-2000 poetry movement in Romania, Fracturi.)

from Alwarda (2020)

2 bucharestromania

I am in the capital city of the world, of my heart, at the end of three days of subdued restlessness. This is not my place. My friends will die, it will be as if we had never existed at all. They are in pain already, I know that by and large we are talking here about mechanisms of functional adaptation only in part, the wrong part, the one which lends a gasoline taste to the mouth. This I studied for seven years, between 1999 and 2006, day in, day out, attentively. Deviated mechanisms, small genetic cracks, plus lately physical pain and a small absence somewhere in the back, small, but everlasting. The physical pain helps. I have learnt that you must bring about pain in one place to be able to numb it in another. Like a sort of black paint trickling from one dot to another. From within the temples to the collar bone, to the ischium, and then again, systematically, to the thirteen facial bones. These are in fact the dots which you can see from skyborne planes, taking over the map. Then I go back. The room is white, the breath mists up the window and causes it to explode. You must bring about pain. The room is all white, it floats above the city, suspended ever since the june of 2006, above the city. I fall asleep, I wake up, I fall back asleep.

2 bucureștiromania

Sînt în capitala lumii, a inimii mele, după trei zile de agitație tăcută. Nu e locul meu aici. Prietenii mei vor muri, va fi ca și cum n am fi existat vreodată. Suferă deja, știu că în mare măsură e vorba de mecanisme ale adaptării funcționale doar pe jumătate, jumătatea greșită, cea care dă un gust de benzină în gură. Am studiat asta timp de șapte ani, între 1999 si 2006, zi de zi, cu atenție. Mecanisme deviate, mici fisuri genetice, plus mai nou durerea fizică și o mică absență undeva în spate, mică, dar pentru totdeauna. Durerea fizică ajută. Am învățat că trebuie să provoci durerea undeva ca să o anulezi în altă parte. Ca un fel de vopsea neagră care se scurge dintr un punct în altul. Din tîmple la claviculă, la ischium, apoi din nou, metodic, la cele treisprezece oase ale feței. Sînt punctele care se văd din avioane de fapt, invadînd harta. Apoi mă întorc. Camera e albă, fereastra se aburește de la respirație, explodează de la respirație. Trebuie să provoci durerea. Camera e albă, plutește deasupra orașului, suspendată din iunie 2006, deasupra orașului. Adorm, mă trezesc, adorm din nou.

(traducere: Rareș Călugăr)

Ștefan Manasia

(b. 1977; poet, prose writer, essayist. Founder of the influential reading club Thoreau’s Nephew. Editor of the Tribuna magazine.)

SO/NN/ET

În lunca suferinței vieții mele

arinii și răchitele-s argint topit;

sacii de pempărși stivuiți sub stele

păzesc ovalul pond azi otrăvit.

Cuirasele țestoaselor s-au risipit:

sînt molecule sidefate, grele,

în damful roz de după pod ivit,

balon gigant al pubertății mele.

Și fesele bombate ale Deliei au zîmbit

cînd ploaia ne-a udat pînă la piele.

În vara aceea am domesticit

oxizii violet din ochii fetei rele.

Și cînd dăruiește femelei albina prigoria –

mi-amintesc din vis doar atît – frumusețea este memoria.

SO/NN/ET

In the meadow of my life’s scars,

alders and wickers are molten gray

sacks of diapers stacked under stars

watch the septic oval pond of today.

The heavy armor of the turtles’ gone:

the hefty, nacred molecules stood

in rosy scent from the bridge pylon,

a giant balloon of my boyhood.

And Delia’s round buttocks smiled

when rain soaked us to the skin.

That summer we managed to unwild

the violet oxides of the girl’s seein’.

And when the robin gives its mate the bee

All I remember of my dream is this – beauty is memory.

Din volumul Cerul senin, 2015. Traducere în engleză de Clara Burghelea.

Radu Vancu

(b. 1978; poet, novelist, translator. Organizer of the Poets in Transylvania Poetry Festival. President of PEN Romania.)

[from the volume Psalms, Casa de editură Max Blecher, 2019]

Master of children’s small fingers

& of the indestructible hair of girls

& of the transparent shields of the gendarmes –

today I saw videos of children with broken heads

& fingers broken, I saw girls dragged by their shiny

& indestructible hair by gendarmes with shields transparent

as your indestructible light, I saw

indestructible teeth broken, indestructible bodies

shattered, I saw the blood made by you

splattering in the world made by you

& there was still so much beauty in it

& it is exactly this that mashes me.

Any amount of beauty mashes me.

An indestructible beauty in a world blown into pieces –

your cynicism is divine, indeed.

I saw a dog licking the bleeding face

of his mistress, collapsed under the boots of the gendarmes,

careless to their blows which also crushed his ribs.

He wagged so happily his tail

when she raised her grazed hand & patted him,

there was so much indestructible light around him,

for him the evil only passed accidentally through the world.

A cop with a high visor, a blond & pure child,

came running & hit her again.

Master, I sometimes tell myself you only passed accidentally

through the history of the world you made, just as we pass

only accidentally through the poems we write.

And that it is of your indestructible & luminous beauty

that the hardest transparent shields are made.

And that the happiest of us are wagging our tails,

licking the bleeding faces of our loved ones. Mashed

under the boots of the seraphim rapid intervention units.

Terrorized by the anti-terrorist units of the angels.

Who to endure so much beauty

– and until when

– and why.

You unbelievably gentle master, if I wouldn’t feel sometimes

your harsh tongue licking my bleeding brain,

if I wouldn’t see your furry tail sometimes

wagging happily – everything would be easier

& more unbearable. Don’t worry, we’re talking here

between indestructibles.

Meștere al degețelelor de copii

& al părului indestructibil al fetelor

& al scuturilor transparente ale jandarmilor –

Am văzut azi filmulețe cu copii cu capete sparte

& degete rupte, am văzut fete târâte de părul strălucitor

& indestructibil de jandarmi cu scuturi transparente

precum lumina Ta indestructibilă, am văzut

dinți indestructibili sparți, trupuri indestructibile

sfârtecate, am văzut sângele făcut de tine

țâșnind în lumea făcută de Tine

& era încă atâta frumusețe în ea

& abia asta mă terciuiește.

Orice cantitate de frumusețe mă terciuiește.

O frumusețe indestructibilă într-o lume făcută țăndări –

cinismul Tău e divin, într-adevăr.

Am văzut un câine lingându-și pe fața însângerată

stăpâna prăbușită sub cizmele jandarmilor,

nepăsător la șuturile lor care-i striveau și lui coastele.

A dat atât de bucuros din coadă

când ea și-a ridicat mâna zdrelită & l-a mângâiat,

era atâta lumină indestructibilă în jurul lui,

pentru el răul trecuse absolut întâmplător prin lume.

Un jandarm cu viziera ridicată, un copil blond & pur,

s-a apropiat în fugă & a lovit-o iar.

Meștere, uneori îmi spun că ai trecut întâmplător prin

istoria lumii pe care ai făcut-o, cum trecem noi

întâmplător prin poemele pe care le scriem.

Și că din frumusețea Ta indestructibilă & luminoasă

se fac cele mai dure scuturi transparente.

Și că cei mai fericiți dintre noi dăm din coadă,

lingând fețele însângerate ale celor dragi. Terciuiți

sub bocancii unităților de intervenție rapidă ale serafimilor.

Terorizați de unitățile anti-teroriste ale îngerilor.

Cine să îndure atâta frumusețe

– și până când

– și de ce.

Meștere necruțător de blând, dacă n-aș simți uneori

limba ta aspră lingându-mi creierul însângerat,

dacă n-aș vedea uneori coada ta blănoasă

bâțâindu-se fericită – totul ar fi mai ușor

& mai insuportabil. Nu te teme, vorbim

ca între indestructibili.

![[from the volume 4 A.M. Domestic Cantos, Casa de editură Max Blecher, 2015]](https://plumepoetry.com/wp-content/themes/cardinal/images/default-thumb.png)