Survivor’s Notebook

Dan O’Brien

Acre Books, 2023

In the Theater of the Prose Poem: Dan O’Brien’s Survivor’s Notebook Makes Melody and Meaning From Pain

by Amanda Newell

It would be easy enough to call Dan O’Brien’s latest collection, Survivor’s Notebook, a prose-poem sequence—it’s what the book calls itself. Drawing on elements of collage and memoir for this hybrid work, O’Brien offers a deeply compelling portrait of life as a cancer survivor. Yet, to call Survivor’s Notebook a hybrid or a prose-poem sequence doesn’t fully capture everything that this book is, or everything that O’Brien manages to accomplish with it.

Hybrid works by definition defy categorization. That’s part of their beauty. Still, even after reading Survivor’s Notebook numerous times and interviewing O’Brien about it for another publication, I found myself struggling to describe why the texture of it feels so different to me.

As I reread the book in preparation for this review, I kept this question at the forefront of my mind: What does make Survivor’s Notebook so different from the vast number of other contemporary hybrid poetry collections? The answer, I discovered, has much to do with O’Brien’s sensibility as a playwright.

~

O’Brien has always been comfortable toggling between plays and poetry, often writing in both genres about the same subjects—consider, for example, two of his award-winning works: his play, The Body of an American, first produced in 2012, and his poetry collection War Reporter (2013). Both examine his unlikely friendship with Paul Watson, whose 1993 photo of the desecrated body of a U.S. soldier in Mogadishu shocked the public and exposed the government’s unwillingness to acknowledge its military failures in Somalia. That photo would win Watson a Pulitzer for his reporting, but it came with a heavy psychological cost for him, in large part because of what O’Brien has called the transgressive nature of Watson’s decision to take the photo in the first place.

Watson was in many ways a natural subject for O’Brien, who has written and spoken extensively about his own traumas—the abuse he suffered as a child, witnessing an older brother’s (failed) suicide attempt, and then later being disowned by his family. The play is less about war, per se, than it is about the bond that develops between these two men as they struggle to come to terms with their respective traumas, which are, of course, entirely different kinds of wars.

How does one live in the wake of trauma? How do we remake ourselves after trauma? These are the questions that interest O’Brien. It’s this same compulsion to interrogate, to bear witness, and to interrogate what it means to bear witness that animates Survivor’s Notebook. For O’Brien, finding meaning is less about “the answer” than it is about asking the right kinds of questions.

~

The shadow of another, very real war lurks in the background of Survivor’s Notebook, which is appropriately divided into five sections that cycle through different seasons of recovery, starting with “Spring,” then moving to “Summer,” “Fall,” “Winter,” and finally, “Spring, Again.”

“Fish Market” appears in the first “Spring” and provides necessary context. O’Brien writes of living in New York City in the early 2000s and waking up with his girlfriend, who is now his wife, on the morning of September 11, 2001, “to the sirens and the Tower on fire, and the next Tower hit as I dawdled on the street gawping. The stench in the air we took into our lungs was ash, glass, cinders, flesh, bone—what would one day give us cancer.” Fourteen years later, O’Brien’s wife was diagnosed with cancer, and his own diagnosis followed not long thereafter. By then, they were living in California and raising their daughter, who was too young to understand she was facing the prospect of losing both her parents to cancer.

In Our Cancers (Acre Books, 2021), O’Brien conveys the weight of their grief, anger, and worry in sparse, highly lyrical, fragmented sequences. Survivor’s Notebook is equally beautiful in its sonic richness. And while it does retain some structural elements of fragmentation with its single prose poem blocks of varying length, which suggests mutability and impermanence, O’Brien’s tone is decidedly different in this collection. He has found, or at least rediscovered, his voice, and he’s ready to talk about everything from his “unspeakable almost cellular sense of humiliation” after his family “severed ties” with him to the indignities of being washed post-operation by a nurse, who, he says, “was the only one with enough—what, callousness?—to acknowledge the squalor of my sex, and in particular the glans the catheter tube split so obscenely.” He talks about his reawakening desire. In “Lazarus in Remission,” he wonders, “Can he go back to having sex? Can any woman bear the touch of where he’s been? Or does he always look a little off, what with his earthen skin and his beard of white lichens?”

~

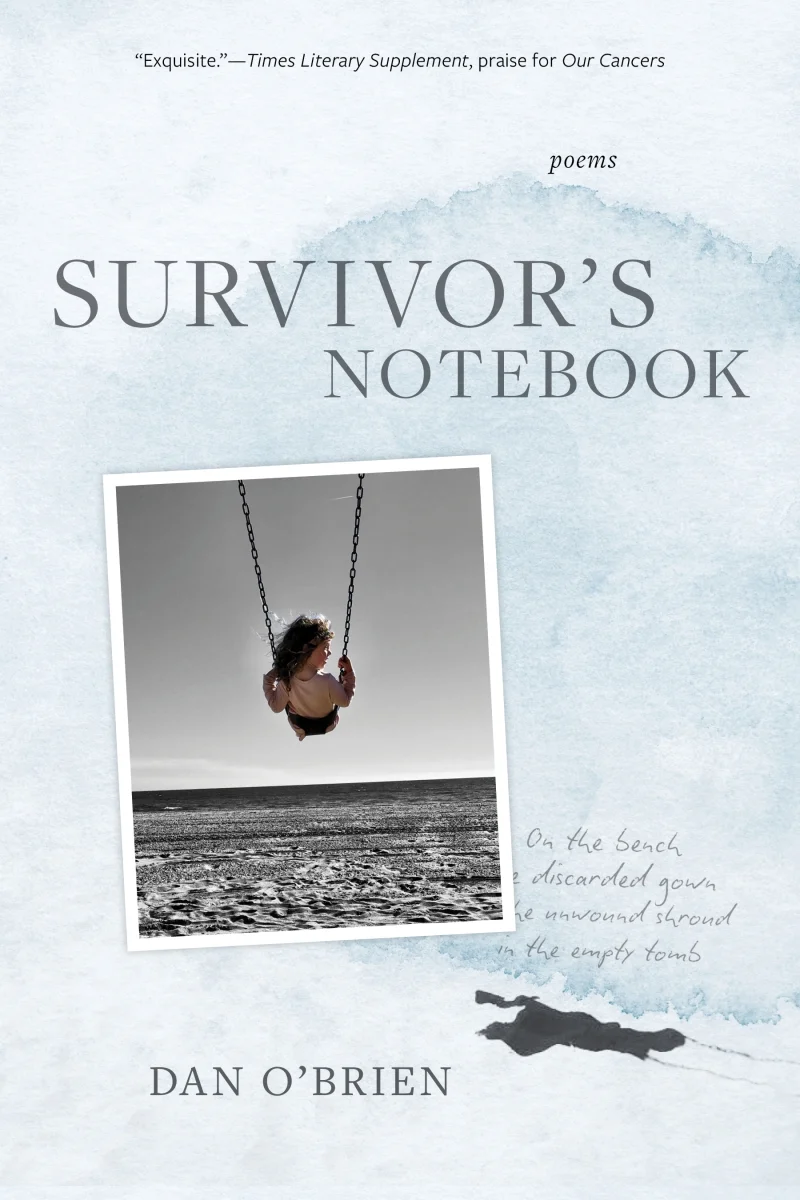

This is a highly “peopled” collection, which makes sense. As O’Brien’s recovery progresses, there is more of that precious commodity—time—for him to reflect upon relationships past and present; there is time again to consider the possible as “[t]he future contains and uncages itself.” Interspersed throughout the collection are many of his own personal photos, a number of which feature his daughter, who emerges as a central and restorative figure, even as the possibility of recurrence is never far away.

In fact, cancer does recur—so frequently and in so many other people O’Brien knows or knew—that it becomes darkly comical:

Everybody has cancer, everybody has had cancer, everybody will

survive. Everybody will die of it; or something. Everybody requires

consolation or advice, guidance or silence. It’s common.

Cancer, in other words, is part of life. If O’Brien can’t control that fact, he can at least control the narrative. This is most evident in the shorthand he often uses when speaking about the recently diagnosed or those who have succumbed to cancer—the war poet’s wife who “died of breast,” the poet who “passed away of lung,” or his wife’s coworker who “survived stage 4 throat.” We understand what he means. He doesn’t have to say the word. But its erasure is powerful because it replicates textually what we know to be true in life: whether we have it or not, cancer is there, even if it’s not—everybody has it, everybody has had it, everyone will survive, everybody will die of it. Understanding this, as O’Brien teaches us, is ultimately a Keatsian exercise in negative capability.

~

Over and over again, I found myself scribbling the words, “the urgency and immediacy of presence,” in the margins of Survivor’s Notebook. The collapsing of the fictional distance between the speaker of the poems and O’Brien himself contributes to this sense of urgency and immediacy, as does the compression the prose box exerts on monologue. But what happens when you couple this approach with an attentiveness to presentation? You get the kind of intimacy that exists, say, between the audience and the actors in the best kind of play: the one from which we cannot look away.

There are two important points to make about O’Brien’s presentation. The first has to do with how the poems look on the page. Each poem carries a title, and because they are sequenced, they don’t appear on separate pages, as they would in a more traditional collection. In a typical prose-poem sequence, the poems might be numbered, or there might be white space or punctuation between each poem—I tend to think of each prose block as a car in a long train. But in Survivor’s Notebook, the poems sit differently on the page. The result is that it feels more like we’re being ushered from room to room, each with a different set. Which brings me to my second, and final point: this helps foreground O’Brien as the speaker inviting us to bear witness to his survival—and by extension, our own.

~

O’Brien has said that he’s a “playwright moonlighting as a poet,” but I don’t think that’s really true. These distinctions don’t ultimately matter. As a playwright, he well knows the ‘Old Masters’ wrote their plays in verse. And like the Old Masters, he understands how our human songs are “made melodic with pain.”