In “Done With Desire Forever, Color Music Poems From The Eighteenth Century,” Rosalind Holmes Duffy revisits Louis-Bertrand Castel’s 18th century invention, the ocular harpsicord, a prismatic instrument that invited its audiences “to consider the instrument as a technical and scientific marvel—enumerating parts, describing the machine—in order to imagine feeling the amazement and transformative multi-sensory high of color music.” Duffy illuminates a fissure in The Age of Reason by recounting the passionate but fatuous celebration that the ocular harpsicord initially enjoyed by scientists, including Sir Isaac Newton, and poets alike. In so doing, Duffy documents a historical example of the seductive sway of intuition, supposition, and tendentious human need for people to believe in the casuistry of an idea if it is poetic and logical-sounding enough.

–Chard DeNiord

Done With Desire Forever

By Rosalind Holmes Duffy

Regardless of how much eighteenth-century French poetry you read, you may be unfamiliar with the miniscule canon of verse about color music. It can be understood as a subgenre of poems celebrating the arrival of science, heralded by Newton’s discovery of universal constants like gravity. It also involves some colorful characters that you will certainly not have heard about before and offers an exquisite, vivid insight into the preoccupations of an age undergoing transformative change.

Among Isaac Newton’s many contributions to his time, the discovery that white light is a composition of all the colors rather than a homogenous absence of color was celebrated as a special sign of things to come. Science, that brave new way of looking at the world and understanding it, was both a means of grasping the rational structures of existence and an opportunity to experience awe. As Alexander Pope put it in a famous epitaph: “Nature and nature’s laws lay hid in night; God said, ‘Let Newton be’ and all was light.”

When he published his optical research, Newton falsely claimed that the colors of the spectrum followed the same proportions as the string divisions that make up an octave. The history and context of this claim are too complex to capture here, but it made Newton’s spectrum research feel more intuitive and convincing than it would otherwise have done, which conferred a reputation and credibility upon Newton himself at a time when nobody yet knew or cared what he was doing. This lie was both persuasive and effective, and before they realized that it was wrong, people spent a lot of time trying to get their minds around what it meant. In 1725 Paris, Newton’s optics inspired the invention of the ocular harpsichord, an instrument that proposed to arrange the colors of the spectrum into a scale so that they could be played as “color music”. In a series of articles published in a popular magazine, the Mercure de France, an eccentric Jesuit scientist and journalist, Louis-Bertrand Castel, proposed to attach each key on a harpsichord to a box that would emit a concentrated beam of light in that note’s corresponding color. While this laser-like effect could not be achieved until the advent of electric lighting, there were multiple prototypes and projects to construct this instrument throughout the eighteenth century, most of them attempts by Castel himself. The ocular harpsichord became a widespread object of fascination and a cultural phenomenon, of a piece with its era’s signature blend of rational precision and entertained astonishment. An invitingly accessible writing prompt, color music lingered in the public imagination up until the revolution.

The earliest verse reaction to the concept is an anonymous comic and satirical poem, wherein the poet imagines a connection between color music and a once-in-a-lifetime appearance in Paris of the aurora borealis, which took place on October 19, 1726:

That night, there was such a commotion!

The Earth trembled under our feet

and from the North-Eastern horizon,

a beam rose, our gazes to meet.

Rays without number in ravishing color

Were seen and then heard to make occult sounds.

This divine clarity was, in a nutshell,

the stunning machine of Father Castel

and it stayed in our sights till it finally fell

in the shade of the sun and the moonlight, as well.

La nuit venant l’Olympe se troubla

Et sous nos pieds la terre s’ébranla :

Puis apparût clarté des plus brillantes

Vers Aquilon: innombrables rayons,

Diapasonnez de couleurs ravissantes

Se firent voir, rendant occultes sons.

Bref de Castel l’étonnante Machine

L’on reconnût, et la clarté divine

Ne disparût, et du tout s’éclipsa

Que quand Phèbé, dans son sein l’absorba.

The poet also imagines Castel as infuriated by the mockery and criticism the ocular harpsichord has invited. In an indignant pique, Castel flies his machine to the moon, a glittering northern-lights tail of color music trailing in its wake. This poem shares its celestial theme with the other poems, which also invoke outer space, the sky, sunsets, sunrises, clouds, rays of sunlight, and rainbows. Cosmic imagery enabled writers to capture the dazzling ambition of the color-music spectacle, the overwhelming sense of awe it was expected to inspire, and its heroic insight into the structures of the universe. Forty-three years later, in 1769, another poet named Lemierre included a celestial passage on the ocular harpsichord in his three-part poem, La Peinture. This excerpt begins with a reference to Iris, the Greek goddess of the rainbow:

But that the day star in the wake of a long storm

far throughout steamy mists throws its visual form,

that it shows to our gazes so sweetly amazed,

upon Iris’ scarf, its divided rays,

this great arc that over heaven spans the size,

this pendant prism that embellishes the skies,

where with happy chords this color, gleaming,

holds the note just left, and the note ensuing,

where the effect of an art unseen and supreme

makes the tint both no more and the same, it would seem,

revealing, by lots of unconscious connections

the contrast in tones on the edges of sections.

Ocular harmony across the sky vistas

shows you the genius of concerts of colors.

Mais que l’astre du jour après un long orage

Dans d’humides vapeurs lance au loin son image,

Qu’il montre à nos regards si doucement surprise

Ses rayons divisés sur l’écharpe d’Iris,

Ce grand arc qui des cieux traverse l’étendue,

Ce prisme suspendu dont s’embellit la nue,

Où par d’heureux accords cette couleur qui luit

Tient du ton qu’elle quitte et du ton qui la suit,

Où par l’effet d’un art invisible et suprême

Cette teinte n’est plus et semble encore la même,

Où laissant voir partout d’insensibles rapports

Le contraste des tons ne parait qu’aux deux bords,

Aux campagnes du ciel oculaire harmonie

Du concert des couleurs te montre le génie.

The reference to Iris also appears in poetry about the instrument written by its inventor:

Messenger of the Gods, whose imbecile verve

consigns a vain song to vile couplets of verse,

Iris—whose return to the sun, up on high

disentangles the splendid and shiny device

from a grim vapor chaos, which lifts a great tide

of our sins from abysses a thousand voids wide—

plans to loose lightening on what’s left of man

but the bolts become rainbows, undone in her hand.

Messagère des Dieux, qu’une verve imbécile

Consacre aux vils couplets d’une chanson futile,

Iris dont le très haut au retour du soleil

démêlant le superbe et brillant appareil

dans ce chaos affreux de vapeurs, que nos crimes

soulevaient à grands flots de mille et mille abîmes,

prêt à lancer la foudre au dernier des humains,

la vit à ton aspect s’exhaler dans ses mains.

These lines, never published, come from the manuscript for Castel’s last book about the ocular harpsichord, where there are at least two other versions of the lines where the lightening Iris holds collapses into its constituent colors. All of these poems are didactic, but Castel’s verse in particular uses heavy rhetorical embellishment and formal constraints, creating the slightly plodding effect of being lectured to.

This didactic style was apt to some extent as color music was understood as a combination of Newton’s cutting-edge but obscure discoveries in physics, and ancient esoteric knowledge. Color music was related to the Pythagorean concept of the music of the spheres, the idea that the planets formed a scale whose music is inaccessible to human powers of perception, but yet somehow perceptible on an intellectual and aesthetic level because of our ability to understand proportion. Pope’s Essay on Man invoked optical tools like microscopes and telescopes and the music of the spheres to imagine a world in which the human senses are so exquisitely sensitive that the finer pleasures we are capable of now—the smell of a rose, the sound of the wind—are either drowned out by sensory noise or have become unbearably intense:

Why has not man a microscopic eye?

For this plain reason, man is not a fly.

Say what the use, were finer optics giv’n,

T’ inspect a mite, not comprehend the heav’n?

Or touch, if tremblingly alive all o’er,

To smart and agonize at ev’ry pore?

Or quick effluvia darting through the brain,

Die of a rose in aromatic pain?

If nature thunder’d in his op’ning ears,

And stunn’d him with the music of the spheres

How would he wish that Heav’n had left him still

The whisp’ring zephyr, and the purling rill?

Perhaps our senses have natural limitations because we’re only designed to experience a very thin slice of existence. And yet, how many sensations pass through us unremarked simply because nobody has taught us to expect them? Color music was an imaginary temple in which one could consider thorny questions and contemplate the brevity of life, the limits of the senses, the subjectivity of experience, the consequence of science, and the potential scope of knowledge. If every rainbow were also an octave scale, that would mean that harmony and pleasure were objective, fixed, and universal across all the senses. In that case, perhaps the senses could also be refined and taught to expand their range and sensitivity. Perhaps people who had lost senses could make up for them elsewhere, or even grow them back again.

For Castel, a Jesuit monk and teacher, the ramifications of this idea were explicitly religious. “Happy is he who believes without vision,” Castel wrote in a poem published to commemorate the completion of the first prototype, “the soul sees, so sensation is illusion.” Color music was not just a physical discovery, it was a divine revelation. It was a universal harmonic code that had overarched all pleasure since the dawn of time while hiding in plain sight, splashing its secrets in the sky whenever sun shines after rain.

While Castel saw himself and his machine as helping to usher in the future, his piety put him into conflict with readers who saw Newtonian science as dispelling the superstition and inequity of the old order instead of reinforcing it. Many of Castel’s contemporaries wanted the future to involve less power in faith and less faith in power. They wanted to celebrate color music’s championing of calculation and proof where before there had merely been myth. In this 1738 poem, the poet imagines an allegorical “fable” bursting into tears and retreating into the void upon hearing Newton’s voice. Once the fable leaves with all its gods in tow, it is replaced by “analysis” and “eternal laws”, whose product—color music—is more spectacular than myth could ever hope to be:

At his voice the sobbing fable

with its Gods to nothing flies;

a more empyrean marvel

sprawls us over other skies.

But a cloud is cracking open.

What glimmer chased the pastors?

The sun is set aglow and Newton

discovers light and colors

I hold a glass triangle.

I analyze, intent upon

eternal laws to disentangle

the rainbow phenomenon.

Oh, chords of rays! Amazed, I hear

their concert’s harmonies go by,

as what notes do in the ear

colors do within my eye.

A sa voix la Fable éplorée

Rentre au néant avec ses Dieux ;

Un plus merveilleux Empirée

Vient nous étaler d’autres Cieux.

Mais d’un nuage qui s’entr’ouvre

Quel éclat chasse les Pasteurs ?

Le Soleil luit, Newton découvre

Et la lumière et les couleurs.

Un verre en triangle, analyse

Les couleurs en l’ordre éternel;

Et ma main tien, range et divise

Les prodiges de l’Arc-en-ciel.

L’accord des rayons, ô merveille!

Forme un concert harmonieux.

Ce que les tons sont à l’oreille,

Les couleurs les sont à mes yeux.

The ocular harpsichord has a habit of emerging unexpectedly from 18th-century texts like a jack-in-the-box or a cuckoo clock or a trickster god. In prose texts, it sometimes has the air of showing up to the party uninvited; it is often unclear what the ocular harpsichord is doing there, as it is usually invoked to make or reinforce some kind of obscure and now forgotten argument. In poems, the intended effect is usually obvious. These poems invite readers to consider the instrument as a technical and scientific marvel—enumerating parts, describing the machine—in order to imagine feeling the amazement and transformative multi-sensory high of color music. Probably the best example of this is “Stances on the Ocular Harpsichord”, from 1739:

Indulge in a new kind of show,

Natives of limitless space,

A mortal stood up and said ‘no!’

To that which has kept you in place.

Under his powerful fists

Cowardly, raw prejudice,

Trembled, was beaten and fell.

As precise calculation disarms;

As sound offers color its charms,

Notes offer virtue, as well.

What torrent is flooding my soul

With ever more genuine pleasure!

On fire and out of control,

I am done with desire forever.

Jouissez d’un nouveau spectacle,

Habitants du vaste univers,

Un Mortel a levé l’obstacle

Qui tenait votre esprit aux fers.

Le préjugé vif et timide

Sous les coups du nouvel Alcide,

Frémit et succombe abattu ;

Un calcul exact le désarme

Du son la couleur prend le charme,

Et, des tons amis la vertu.

Quel torrent inonde mon âme

Des plus légitimes plaisirs !

Le transport excité, l’enflamme,

Je ne forme plus de désirs.

The author of these lines was Descazeaux, a poet and playwright whose literary career came to a dramatic halt a year later to the month. In April 1740, determined to get the powerful theatre troupe, the Comédie française, to perform his plays, Descazeaux wrote them two threatening and unhinged letters making outrageous claims about his talent, connections, and influence. He lived practically next door (between the local baker and the rotisserie shop) and it seems that the actors became concerned for their safety. Instead of caving into his demands, the troupe used its connections to the king to have the poet arrested and thrown into a lunatic asylum. His neighbors around the Comédie française (including the rotisseur, the baker, the jeweler, the hatter, the wigmaker, and the limonadier, or bartender) petitioned the Lieutenant General of the Police for his freedom. They had, they wrote, always known him as “a tidy young man of good life and morals, calm, and not at all afflicted by madness”.

Several weeks later, Descazeaux was free. However, he was banned from entering any café or public space, including the theatre. This meant that he was effectively exiled from public life, cancelled on the King’s authority. In the words of scholar Gregory S. Brown, “he found himself physically prevented from entering the public arena, a writer in no one’s consideration but his own.”

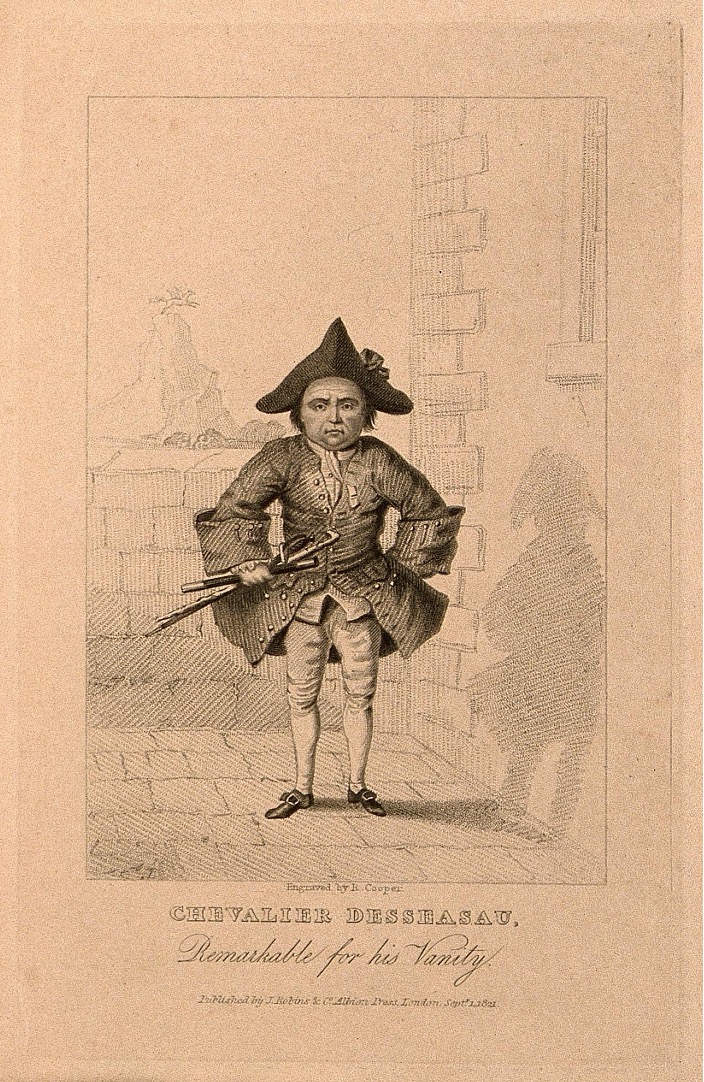

Yet it seems that this was not the end of Descazeaux’s career as a man of letters. Shortly after this episode, a narcissistic and unhinged French poet named Chevalier Descazeaux (or Descassau or Desseausau) moved to London and spent the rest of his life there. This individual came to England with a story about having deserted his commission in the Prussian army following a duel in which he nearly murdered his opponent. He then became a notable eccentric personality in literary circles. According to Wonderful Characters: Comprising memoirs and anecdotes of the most remarkable persons of every age and nation, Desseausau “either had, or fancied that he possessed a talent for poetry, and used to recite his compositions among his friends. On these occasions his vanity often got the better of his good sense and led him to make himself the hero of his story.” Descazeaux (or his double) imposed himself upon the London scene by striding around in unusual clothes, carrying two swords, and exuding a magnetic “ask-me-about-my-two-swords” energy:

He appeared in the streets in singular dress and accoutrements delineated in our engraving. His clothes were black, and their fashion had all the stiff formality of those of an ancient buck. In his hand he generally carried a gold-headed cane, a roll of his poetry, and a sword, or sometimes two. The reason for this singularity was, according to his own expression, that he might afford an opportunity to his antagonist, whom he wounded in the duel, to revenge his cause, should he again chance to meet with him. This trait would induce a belief that his misfortunes had occasioned a partial derangement of the chevalier’s intellects.

Descazeaux was incarcerated yet again in Fleet Prison after falling into debt, so his life had ups and downs. Yet he was well-known and liked and an impressive collection of compelling portrait prints of him survives in various archives. There is also a drawing of him in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery. He’s typically depicted as short and cross, holding the two swords, and being skewered for his vanity:

Descazeaux’s poem on the ocular harpsichord was published in the Mercure de France, a monthly magazine that was paperback-sized and a thousand pages long. The Mercure had a special relationship with Castel and his invention, having published the first articles introducing the idea. A varied and sophisticated account of current events, culture, and gossip, it was capable of announcing that 200,000 people had died on the other side of the world on one page, printing a comic sonnet on the next, and then, on the page after that, revealing that the wife of a baker on the rue du bac who gave birth to a girl three weeks before had unexpectedly given birth again, this time to a boy.

The editor of the Mercure was the urbane librettist and peg-legged art collector, Antoine de la Roque. The scion of an old Marseille family of merchants—his father was one of the traders who introduced coffee to France—Antoine de la Roque took over the Mercure with his brother as part of a plan to make back a lost family fortune (the leg was lost for good, however; blown off by a cannonball in Oudenaarde). It seems that Antoine inherited his father’s skill in networking and earning people’s trust, as according to one of his friends: “The decency, good manners, candor, and sincerity that shaped his character and was written all over his face attracted the esteem and veneration of everyone who met him.”

We can see this face ourselves in a 1718 portrait by rococo painter Watteau, now in Tokyo’s Fuji Museum. De la Roque lounges in the foreground with his cane, gesturing meaningfully towards his artificial leg, his hair and clothes in a casual but artful state of deshabille. To his right he has discarded a lyre, flute, and manuscript (a nod to the libretti) and a suit of armor (a recollection of his soldiering days). His face is the absolute picture of boredom, but it is the boredom of a person with too many delights to choose from, not too few.

Fig. 3 Watteau, Portrait of Antoine de La Roque (1718)

He is not the slightest bit curious about what is going on in the delightful grove behind him, where a group of nymphs and satyrs has apparently paused mid-orgy to have an intellectual discussion. In fact, they are concerned about him; one satyr shushes the rest of them so as not to interrupt Antoine’s exquisite melancholy. Ignoring his dog (who, with no idea he’s in a painting, wags while looking up at him) de la Roque gazes out at us, his attentive public, as though hoping that we might do something to relieve his great ennui. “Please do something new and interesting,” he moans, “Won’t somebody please respond?”

To his credit, the public did respond, and by the time he died in 1744, he had more than made back his fortune. The Mercure was a huge success, and one of the reasons for that is that it was an interactive forum. Many of its articles were penned by readers, who either saw something they thought would interest others and wrote in to break the news or had sent a letter to a friend that was so attractive and well-written that eventually someone said, “This should be in the Mercure!”

Perhaps this is what happened to Descazeaux when someone first read his poem on the ocular harpsichord, which he began by calling for the muses to awaken his genius and deliver it from chaos. Indeed, these poems share a preoccupation with chaos, nothingness, the void—ordering it, escaping it, pulling things out of it and banishing things into it. In combination with cosmic imagery, focus on chaos paints creation as a domain of absolutes: chaos and order, sound and silence, being and not being. It evokes journeys, the struggle to become, the process that turns ignorance into discovery, the unthinkable space between rainbows and the music of the spheres. Chaos conjures The End, and for Descazeaux, the ocular harpsichord was the end of desire. His poem has a line, rendered above as “I am done with desire forever”, whose literal translation is more specific: “I do not form any new desires.” Color music promised to extinguish longing with a sensory onslaught so overwhelming and complete that it would render new experience redundant. This was a riveting possibility to contemplate, whether you were a poet contending with poverty and your own tenuous grip on the truth, or a swaggering entrepreneur jaded by the infinite variety available to you.

Chaos also evokes insanity, and frankly all this talk of musical rainbows is destabilizing. Castel himself was described as crazy by multiple figures including Rousseau and Diderot. Yet as preoccupations go, chaos is an understandable one. What better reaction is there to the experience of trying to make sense of your place in a vast, indifferent universe of which you can perceive only the tiniest sliver and about which you understand practically nothing? This is not to mention the subsequent experience of looking around and realizing you’re surrounded by billions of other people who have no more information about what’s happening than you do. In the face of such uncertainty, one could do worse than to imagine that there is music somewhere over the rainbow, a cosmic balance in the face of which your limits and your longings melt and leave you staring at the sky in pure amazement.

Note: Perhaps it is too strong and unjustifiably provocative to say this was a lie; indeed,

the mystery of this story is how we should think about Newton’s seven-color

convention and what it was, if not a lie. It was not a temporary slip or an idle mistake:

Newton evidently believed that color music should be true and tried repeatedly to find a

way to prove it.

Newton was an extremely private, solitary man and his research on the spectrum

was the subject of his first publication. He had no reason to expect that anyone would

trust him blindly when he began to make this claim as an unknown scholar in the 1670s,

and it seems that no one did. It is a matter of debate among historians whether his

entrée into the world of public science went horribly or not very well (and who was at

fault), but Newton was so upset by the experience that he stopped answering his letters

and tried to withdraw from the Royal Society.

By the time Pope’s lines were written half a century later, everything had

changed, but Newton’s determination to support color music actually became more

intense over time. Some of the reason for this was that he felt the connection between

notes and colors was intuitive and trusted in that sense of intuition. However, he also

had no valid math to support color music and knew it. Newton’s science was marked by

an obsessive commitment to accurate measurement, so it is extraordinary that he

continued to insist upon a claim that he knew to be baseless. The story of color music is

all the more extraordinary because of how widely known it became: throughout the

eighteenth century, the prism was the principal symbol of Newton’s science, and before

people realized that color music wasn’t real, a lot of energy was spent discussing how it

worked.