NM: Hey Jeff! You mentioned in a recent phone convo that your most recent book Chance Divine, which won the Field Poetry Award, and was published in February 2017, was a landmark for you in terms of resolving decades of preoccupations/obsessions. What exactly are these?

JS: I’d say Chance Divine was more a crystallization of my obsessions than a resolution. Resolution will have to wait until the next world, I fear. The core problem for me has always been the discrepancy between the felt experience of meaning and the almost equally powerful sense that all is brevity, and that meaning itself may be an illusion.

NM: That’s an interesting and slightly terrifying problem. I guess for me the core problem for me has always been that the felt meaning of experience is at odds with what appears to be the status quo/reality. When I was a kid I’d slip into in my parent’s darkened bedroom and repeat the question “who are you” to my reflection in the my mother’s vanity mirror until I tranced. By holding a hand mirror to the larger one I could create infinite tunnel, which I believed, was a conduit to another “real” dimension. I think that’s why, decades ago, I connected with your work from the get go. In “Nominal Acrostic” from your first book Late Stars, you write

Reality has a thin, metallic surface tension

Every good boy wants to penetrate badly.

I so totally got that.

JS: That’s a very interesting story about your younger self. I can identify! I remember clearly one time when I was little, playing on the kitchen floor. Suddenly I “woke up”—I’d been in a nameless trance, for who knows how long, and I had to think hard for a moment to remember who and what I was. There was some panic before “Jeff,” I remembered finally, “I’m Jeffrey.” It was a spooky moment.

NM: Yes! “Soldiers & Dinosaurs on the Kitchen Floor” from Chance Divine is about that experience, isn’t it?

JS: Yes—exactly!

That morning with sun

On black linoleum

Coming a long way back

From play to myself,

Knowing for the first time

Separation: I belong

Elsewhere. I tried

To save the child, to hide

Him beneath my name

But finally mother

Asked Whatcha thinking?

& I could not answer, my

Face turned up to her,

My dark face in the sun.

NM: Oh-that “I belong/Elsewhere!”-this experience is not unlike, slantwise Elizabeth Bishop’s out-of-body experience in her marvelous poem “In The Waiting Room.”

JS: You’re right—I think Bishop is also talking in that poem, at least in part, about the first real shock of self consciousness, and of being detached somehow from “the body.”

NM: And maybe the paradox of self-consciousness and yet a consciousness of being a part of the sea of universal consciousness?

JS: Maybe. A child has not entirely left that universal sea. But talking about these things makes me uncomfortable because it’s like pretending to stand on the edge of a cliff, from which one can too easily fall into The Sea of Pomposity.

NM: You? Never!

JS: Are you saying I’m incapable of pomposity? How dare you!

NM: You, my dear wunderkind, are capable of anything…but tell me more?

JS: There is vast silliness possible on either side of the binaries, and I have certainly taken part in that silliness. Again and again, I’m afraid. But I am very far from a Positivist, or Materialist, and in my younger days I was very interested in ESP and all that other hippie stuff that was floating in the ether of the time. At the same time I was a psychology major in college (minor in theater), and Skinnerian Behaviorism (nope—no relation!) was the dominant mode. I saw clearly that operant conditioning was a real and useful phenomenon. So I was exposed to both poles. A lot of water has gone under the bridge since then, and though I don’t know much, I think I know two things: science works, and what it discovers has a real and mysterious relationship with reality; and two, there are vast areas that science cannot, by its nature, comment on. People tend to be extremist in this dialectic, but to me there are obvious truths on either side, and one side doesn’t negate the other, or even contradict it, necessarily. So I would like to think of myself as balanced between the poles. Of course, extremism in art is no vice . . .

NM: You are the epitome of balance…it’s just, um, that tinfoil hat you’re wearing…a therapeutic device?

JS: Yes, it’s a prescription tinfoil hat. But the problem really is the trajectory of every human life is an answer to it. So. This morning, for example, while eating an almond croissant, it suddenly occurred to me that there was a similar feeling in Degas’ “The Absinthe Drinker” and Hopper’s diner painting, “Nighthawks.” That’s all. I saw both images and felt the charge of emotion passing between them, like an electrical flash. I have no idea why this came to mind. Then, the next moment, as I was washing down a bite of croissant with strong coffee, the jingle to an early sixties TV toothpaste commercial came barging into my consciousness—“Bucky Bucky Beaver, Bucky Bucky Beaver. . .” over and over, mindlessly repeating. The paintings had vanished, of course. The absurdity of this juxtaposition is something one can discover matched in the external world at any moment, I find, just by being awake. The surrealist landscape that so charmed and entertained me (Dali, Magritte, etc.) in my twenties has become our everyday wallpaper. Only, with a slightly menacing edge. Today American culture (not to mention the rest of the world) is so atomized and subject to every conceivable type of mash up that the thought of a flaneur walking a lobster on a leash is tame in comparison. At least, it seems so to me.

NM: I agree-we’ve become jaded, I’m afraid. Yet, I’d seriously dig having these kind of waking electrical experiences…have you always had such extravagantly palpable flashes?

JS: Well, the painting connection may be interesting. But I don’t think anyone would call the recollection of toothpaste commercial from childhood “extravagant.” And that’s the problem: the mind (my mind; I have nothing to compare it to) goes where it wants to go, and sometimes that’s an interesting place and sometimes it’s banal, or just dumb. It’s rapid transit, and speed itself is fun. Sure. But I never know where I’m going to end up.

NM: Is there anything that you do, rituals, etc. that might increase that receptivity? Substances—caffeine or…?

JS: I do often listen to music (through earphones) when I’m writing. What seems to work best are post rock stuff (like Tristeza or Rena Jones), or contemporary minimalist composers (some Philip Glass, anything by Arvo Part, who I love). But nothing with a human voice. I can’t recommend any substances; even when I used them, long ago, I didn’t write when under the influence—too hard to focus. But when I first started that journey, it’s possible drugs did help to unlock some fruitful parts of the mind. Then again, maybe not. In any case, I wasn’t after enlightenment when I used. I was after oblivion.

NM: Oblivion as an escape from what?

JS: From me, I think. When Samuel Johnson was asked why he drank so much (and he did) he answered, “I drink to send my self away.” That makes sense to me. As it does to roughly ten percent of the human population. And thank god it’s not more.

NM: Yes. So when you’re in “receiving” mode you just write, stream of consciousness?

JS: When I’m writing the focus filters out the junk, for the most part, though I try to keep the signal as wide as possible. That’s a relief, that focus, and tracking consciousness in a disciplined way is part of the pleasure of writing. But my ordinary consciousness goes merrily on. When I was a kid I more than once had a teacher write on my report card something on the order of “Jeffrey is smart, but he spends a great deal of time daydreaming. He needs to look out the window less, and concentrate more on the task at hand.”

NM: Yep, same here. Jeez “the task at hand.” Do you think “people like us”—and David Byrne—were looking, listening for evidence for a world we intuited was out there beyond those classrooms. Again, that “thin metallic surface tension/Every good boy wants to penetrate badly.”

JS: Yes, I think you’re right. There’s also something about the daydreaming state of consciousness . . . I think it occupies the same space as the imagination. It also—though this is a much bigger stretch—may be a little taste of transcendence, a foreshadowing of the life to come. “I loaf with my soul and loaf,” Whitman says. Walt did a lot of beautiful traveling while he was loafing . . .

NM: I’m a big fan of Gaston Bachelard who posits that only through reverie, induced by solitary contemplation of natural phenomenon such as fire, water, wind, etc.—hence the looking out the window — can the true poetic impulse be accessed. He’s very careful to distinguish this from a daydream, which makes us dreamy and sleepy—”it’s a poor reverie that invites a nap”—whereas a reverie produces a heightened awareness of a universal consciousness, the unified field, the Tao, if you will.

JS: I understand what he’s talking about, and I agree. But I don’t think the state must be induced by natural phenomenon, though it’s certainly one good way. What gets one there—into the “zone,” or whatever one calls it, can be varied, I think. Milosz said, “nature bores me”; and in his poems he certainly found a lot of transcendent, non-personal consciousness . . .

NM: Well, I ain’t gonna take on Milosz, but there is the Bachelardian idea that nature is a mirror…hmm… if so, maybe what bores Milosz is Milosz! Wait, I did not say that!

JS: By Bachelard’s definition a free climber on a sheer rock face is in reverie . . . which seems right. If he is not to fall.

NM: I think this particular contemplation requires a stillness, a Whitmanian loafing, a letting go, so, I’m not sure if clinging to the sheer face of a rock would qualify…but hey, we’ve got enough going on here without bringing in French philosophy! Back to the obsessions at hand.

JS: Right. Perhaps now we should talk about important matters, like what restaurant makes the best crème brulee, or how you like your toast—lightly golden or slightly burnt? Golden for me. Ok, back to trivia. So I have always wanted to know—and middle age has a way of injecting urgency—is there meaning in this universe, or not? And, how can one know? Am I dreaming it? And, where does such meaning come from? What is it for? Who decides?

NM: But, don’t we decide?

JS: Yes. But just because I say my life has meaning doesn’t mean it does. Not in any absolute (or even, in the end, relative) sense. Epistemology is a huge subject, of course, but the roots of it are simple: it comes out of those questions I just mentioned. One of the possibilities is the one you mention—that we decide what has meaning and where it comes from. But, which we? The problem is that you and Hitler, for example, probably had widely varying beliefs about meaning, and values, and a worldview in general. But he was human (unfortunately) and so are you. Why are your ideas better than his? What is the source of authority for your beliefs? For Hitler’s? If you push it logically, that is not a nonsensical question. Is there meaning that transcends any individual human preference?

NM: Meaning beyond the individual-a collective meaning, a collective consciousness?

JS: Yes—and there are/have been many words, many metaphors for it. It’s a trans-cultural idea, if ever there was one. These are versions, of course, of the oldest philosophical questions. Which also torment me. What I have come to over the past twenty or so years, and tried to enact in the poems at each step along the way, is a slowly evolving worldview that includes equal measures of science and faith, which I do not and never have found to be in conflict.

NM: Isn’t that what poetry is, equal measure of science and faith? I think of Whitman’s “for every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you,” which he wrote long before science stamped it with its seal of approval and Carl Sagan served it up to us on the TV series Cosmos.

JS: Honestly, I don’t know what the hell poetry is. I know it when I see it, maybe. What science is is clearer, though not as clear as some would like to think. And as scientists such as Stephen Jay Gould have said, firmly, there are provinces beyond the purview of science. Science can say that there was a Big Bang, and what happened afterward, and maybe how it came about, but it can’t say why. So there’s plenty of room for the exploratory tool of language, of poetry. Poetry picks up where science leaves off. And I like very much the solid leaping off point science gives me. I have tried to interrogate both science and religion with equal rigor, keeping in mind Plato’s injunction to follow the evidence. And this has led me to believe that immanence and transcendence are two sides of the same coin.

NM: That’s a hard-earned belief.

JS: Everyone has a complete worldview, a belief system, a faith. Some people are unconscious of their worldview, of what they believe in. But everyone has one. It doesn’t necessarily have to do with religion; non-religious worldviews (faiths) can be as strongly held as religious ones. Or stronger. There is no “placeless place” to stand. My belief system has changed enormously since I was young, and aspects of it are still under revision. This is something that interests me, and also seems to me critically important. So I have chosen to be attentive to my beliefs, my faith—its coherence and solidity, or lack thereof—by intense and long devotion. As it were.

NM: Is there a trajectory of these arguments in your other collections before Chance Divine?

JS: Yes. All my books are first cause arguments with myself.

NM: It seems that your fifth book, Salt Water Amnesia really marked a new territory.

JS: Salt Water Amnesia was a departure. I wrote it when I was living in James Merrill’s house in Stonington, Connecticut, as the Merrill House Poet in Residence. I was raised near the Atlantic—on Long Island, and various places along the coast of Connecticut. But I went to Kentucky for the university (of Louisville) teaching job. I liked Kentucky, and I really liked Louisville. But I did miss the ocean. Some people find their “spirit place” is mountains, or rivers, or deserts. For me it’s the ocean. So I came from years of being stranded in the middle of the country, back to the edge, back to the Atlantic. Stonington is a fishing village (or was, until fairly recently), a little peninsula of a town surrounded on all sides by the sea. Living there immediately filled me with new joy and inspiration. The poems are more playful—even when they’re sad.

NM: Yes, they are wonderfully playful, outrageously imaginative!!

JS: Thank you. There’s a jokey ebullience in the poems, I think, which I wish I had more of in my work. Humor is a central human accomplishment, one of the main reasons why god has not allowed us to wipe ourselves completely out of existence. Yet. If I didn’t have, for example, W.C. Fields trying to nap on a porch swing while being harassed by children, salesman, and all manner of other interruption, I personally would find it hard to get out of bed in the morning. Word.

NM: Word. And in Salt Water Amnesia you were playful with form as well…less formal, chattier, more prosy?

JS: As for the prose poem form—I’d always liked prose poems, and had written some before. But Merrill’s house still had his library, which I was free to use. I discovered Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet. That book, along with the sea, opened up a new language, a new, more rangy possibility of what poems might include.

NM: So, in such proximity to the sea, you were in reverie, in a consciousness without memory—you had Salt Water Amnesia!

JS: Yes! I can still taste the waves, feel the salt in my drawers! Arrrrrrrrrgggghhhhh!!! (I also love Talk-Like-A-Pirate-Day)

NM: But seriously, weren’t you were drawing from a different source which had to find another voice, form? Correct me if I’m wrong, but up until SA you’d been working in form?

JS: Yes, that’s true. I even had some association with the “New Formalists” of the eighties. But I always liked Baudelaire, and the American neo-surrealists—I loved the Michael Benedickt anthologies. The prose poem loomed large there. So I was not a very good candidate for any movement; I wanted to try widely varying techniques, tones, etc. When I was putting together my New & Selected (I Offer This Container) it became clear to me that though my obsessions have stubbornly remained what they were from, say, the second book on, I’m formally restive, and like to engage everything from received form to prose poems to collage techniques.

NM: These techniques are apparent in each of your books?

JS: Yes. But the books vary in tone and approach and maturity. Writing is one art that can improve with age, luckily. Can, doesn’t always. With Chance Divine I feel I’ve found the (or, a) balance point between reason and theology, the seen and the unseen.

NM: I’m curious; do these preoccupations inform your screenplays and plays such as Down Range which had a successful run in NYC, Chicago and Harrisburg, PA, and Dream On which had it premier production in 2007 by the Cardboard Collective Theatre in Philadelphia?

JS: I actually wish I could find some activity, writing or not, where they didn’t show up . . . I used to play golf, but arthritis made it increasingly painful, and after I gave it up I noticed with mild surprise that I didn’t miss it. I’ve thought about having a boat, but you really need a body of water for that to pay off, and the Ohio River just doesn’t cut it for me.

NM: Because it’s not salt water! No way for your to talk like a pirate on the Ohio!

JS: Yes! And, yes! Arg.

NM: Anyway, you’d never escape those preoccupations on a boat—didn’t Melville say water and meditation are forever wedded?

JS: Good quote. He was right. Wearing a wing suit and jumping off mountains looks interesting, at least on YouTube . . . But no mountains where I live are nearly high enough, and if I’m going to do something suicidal I want the backdrop to be ultra dramatic. I don’t think that’s too much to ask. I do occasionally write plays (speaking of dramatic, and/or semi-suicidal).

NM: You’re being funny, right? Dad-humor right here, folks.

JS: And what’s wrong with dad humor? Eh? Can’t hear you. Eh?

NM: You know, writing and producing a play is really brave—you’re really putting it out there.

JS: Writing a play is not brave. Ridiculous, maybe. Probably.

NM: Why ridiculous?

JS: I wrote a play last year, Jonathan Agonisties, a one act, one-man show, in which my protagonist enters stage left with blood on his shirt and announces that he’s just come from killing a man. The rest of the play is his story, his justification for the murder, based on the argument that if morality does not issue from a transcendent source—if it is culturally relative, or individually assembled—then murder can be neither good nor bad. Alas, this is what happens when I try to write a comedy.

NM: You’re funny. This play sounds fascinating.

JS: I think so. Though it’s not for me to say. Dammit.

NM: You served as Artist in Residence at the CERN particle accelerator in Geneva, Switzerland the summer of 2015. Did this experience help resolve these life-long preoccupations and validate your instinct/intuition?

JS: Quantum mechanics validates absurdity. Because particle behavior is absurd: a particle can be in two (or more) places at once. Because: once two particles are entangled, the two can part ways—travel to opposite ends of the universe—and yet no matter how far apart, whatever changes in one is instantly reflected in the other.

NM: Holy cow!…so, in a sense, one is always connected to those with whom they have been entangled? If so, there’s no “getting over” anyone!

JS: Yep. The saying, “relationships never end, and always change” has some science in it after all!

·Inside its box Schrodinger’s cat is both dead and alive, right up until the moment someone opens the box and checks, at which point it will be either dead or alive. In a very real sense, without an observer matter can only be said to be a “probability wave,” to possess the potential to exist as dimensional reality.

NM: So, that’s a little scary…so I, as matter, only exist if I’m seen, observed?

JS: Not exactly. Things are complicated unimaginably on the macro level. But it is in a sense the way particles behave, and we are made of particles. So—there must be some relational mirroring . . . This may serve as a example of one of the ways in which I find science and faith not only do not contradict, but may in fact be mutually reinforcing. In my faith—Christianity—god is a Trinity, three persons in one. God’s essence is relational, each person of the trinity in unconditional, self-sacrificing, eternal love with the others. Since we are “made in God’s image,” we are likewise made to be relational creatures. We need the acknowledgement of others, the love of others—and we must return this love in kind—to be what we were ultimately meant to be. The lonely and bereft may come to feel they don’t really exist. In the end it may be we need the love of others simply to be. All of us feel this to some extent, I think, at some point in our lives. Or, at many points. If you haven’t felt it yet, you will. Everyone longs for completion, though they may have different ideas about what that might mean. But I think that in the end all longing is the same.

NM: Yes.

JS: Yes, yes—Eugene Ionesco has nothing on quantum mechanics . . . and yet, quantum mechanics, as laid out in the Standard Model, works. It works better in fact, more accurately, than any other prior scientific theory, even though incomplete. It has given us lasers, transistors, MRIs, and many other tangible acts of wizardry. And yet, and yet: as Nobel Prize winning physicist Richard Feynman said, “I think it’s safe to say that no one understands quantum mechanics.”

NM: Mr. Feynman is master of the understatement.

JS: Yes! There’s also the wonderful story of Einstein, related by another man who was with him on a ship crossing the Atlantic. When asked about it, the guy said, “Every day during the voyage we would talk, and Einstein would explain to me his General Theory of Relativity. By the time we arrived in New York, I was fully convinced that he knew what he was talking about.”

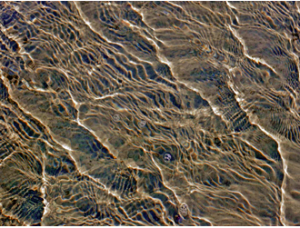

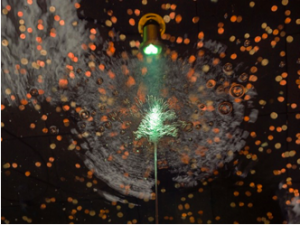

At CERN I saw what I had before only read about; I saw the 27 kilometer particle accelerator. I saw the complex of servers in the computer wing, where the Internet was born. I talked to theoretical physicists who were living at CERN for periods between two and ten years, to think through a problem of their own devise, and to test their thinking against the hard data of the accelerator. I saw images like this created by information from detectors trained on particle collisions:

It was a glimpse behind the curtain at the quantum mechanics—backstage at magic show headquarters. It was exhilarating, transporting me to an altogether new level of mystification and awe. It was avant-garde theater at its best: I thrilled, I puzzled, I laughed. But I did not understand.

NM: But, even if you didn’t understand, did you have/feel a connection with this mystery…or did you remain the observer?

JS: I feel like I have an intuitive grasp. It strikes a chord in me, obviously, or I wouldn’t have pursued it, in my way. There is, of course, a large gap between what I learned and what I later made of that knowledge in poems. Poems are not science, after all.

NM: Why not?

JS: They are different domains. Science is concerned with matter and energy. Just the act of writing poetry belies the belief that matter and energy are all there is. At least I believe that, and I think I could make a case for that belief. What I wrote was speculative. What I’d like to do is to start talking as soon after science stops as possible, though. I want to narrow the gap. Language is a carrier form of information, which some people now believe to be an immaterial but indispensable form of reality, joining its better-understood relations, matter, and energy. And if it turns out there is coding behind or beneath or within we may one day recognize it as language, as the logos. Quantum mechanics makes it easier for me to believe we were (along with all that is) spoken into existence.

NM: Spoken into existence! This is mysticism…maybe you’re a mystic? Why not you?

JS: Two reasons: I’m lazy, and I don’t want disciples. Or, maybe that’s one reason. Also, I don’t think mystics swear much, or eat meat, or sing the Bucky Beaver jingle in their heads . . . I’m just not cut out for it.

NM: Ok, talk about this a little bit…our human consciousness? This is really trippy—like the gurus and sunny-side uppers say, our thoughts really do create reality?

JS: Well, our thoughts create our reality. Whether our thoughts create Reality, whether there is a Reality apart from consciousness—these are the teasing questions, the ones I enjoy playing with. The ones we are batting around here. The universe began some fourteen billion years ago with the Big Bang, which happened either by chance or by design. If chance, then there can be no “meaning.”

NM: But isn’t there meaning in chance itself—wouldn’t the I-Ching and John Cage might argue that there is?

JS: What is chance? If it really exists, then no, there’s no meaning in truly random events. Something either happens by design, or by chance. It’s kind of definitional, no? And if we create our own meaning out of “chance,” then we’re back to what I said about you and Hitler—who has the correct “meaning,” and why? Differences about the answer to that question are at root of many a war, unfortunately. By the way, I’m sorry to force you to hang out so much with Adolf.

NM: Apology accepted; just don’t do it again, buster!

JS: Ok! If everything is a result of chance then meaning is just a human invention and will vanish without a trace when the sun runs out of energy. The word will signify as much or as little as the word plum, for example. But that would make for such a stupid story! So hard to believe! Which is one reason I don’t believe it. Nothing comes from nothing. I believe a reality exists outside the one we can perceive, and in all probability it is the self-sufficient, non-contingent ground of being itself. This is what I want explore, in modest, earthbound human terms, in my poems.

NM: You’re also a photographer—how do you explore this alternative reality in your work, especially these wonderful photos you’ve been so kind to share here with Plume?

JS: These photographs are part of a group called “Living Water,” which formed a show I had up a year or so ago. I go to photography partly because it’s a relief from the (sometimes overbearing) pressure of words, and so I try generally not to add words to the pictures I’ve done. But I can say that in this series I felt like I fell back into a way of seeing I remember vaguely from childhood. When I was a kid I could, and would, stare at things—small things like a leaf, a rock, the surface of a stream—for a long time. When I did this miniature but complete worlds would gradually reveal themselves, kind of like the living marble that contained a universe in Men In Black. There were, it seemed, infinite worlds nested inside this one, and inside each other—you could scale down, and keep seeing a new universe with its own texture and elements and inhabitants and atmosphere. In childhood there is endless time, and I remembered that experience as a kind of ecstatic ongoing exploration. I did not, as you might imagine, play very well with others . . . . So in the series I tried to return to that kind of seeing, looking through the lens of my vintage Hasselblad into various forms of water (creek, lake, ocean, man made fountains, etc.) and taking lots of shots, until I saw and captured another world nested inside the larger one. I still don’t play very well with others, by the way.

NM: These are really compelling and are as mysterious as the photo you shared earlier of the image created by info from detectors trained on particle collisions. Lovely!

NM: Would you say the poems in this feature continue to explore the questions/examinations/exploration of consciousness and being in Chance Divine?

JS: There always seems to be some “spillover” when I finish a book and I’m trying to write new poems. So—yes, kind of. But I don’t know what the next poem will be; I rarely do. Almost never. And I haven’t yet got hold of whatever it is that will eventually organize the next book. So, I’m taking stabs in the dark, and trying to be grateful for whatever fills the page. Unfortunately I’m restive and impatient, and I always find this in-between time difficult. But no one ever said the life of an American poet would be easy. The blessings are real, however, and I’ve had many.

NM: We’ll close on that note of gratitude; thank you for this wonderful ramble. Readers, this wonderful new work from Jeffery Skinner:

Voices, Things, Knowing

I must stop being romantic about the unknown.

If we knew, I’m sure romantic would be the wrong word.

It’s not the unknown that’s romantic, it’s the unknowing.

Oh Jeff! voice chides, the stone in the shoe one,

the one that never shuts up, The unknown is way too big

for your little life. Fuck you! I answer. Then my wife

says Do you have to use that word so much?

And I’m sorry, I say, truly I am. But how is it you hear

my thoughts, my flower? Too late, she’s gone on to other

things she thinks to do, and she thinks of things to do

in unending succession. That’s our division

of labor: she does the doing, I do the being. I know,

I know what you’re thinking—Sweet gig for you!

But really, I find being difficult, if not impossible, while

my wife thinks doing is just what you do, and seems

to actually enjoy it. And maybe it’s because I sit so much

in the middle of being that I think of the unknown as romantic.

Maybe I should get out more, out from behind the screens.

It’s as if I’m locked in a closet with all these voices,

the dark increasing, blotting out one thing after another.

Don’t be afraid, voice says: the last, the essential one.

Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast

The Milky Way spins 168 miles per second,

Earth tear-asses around the sun at 67,000 miles per hour.

I read this online & grip my chair. It feels

Solid, as if justice must be built in to the machinery.

And though it’s hard to believe things

On this planet will turn out right, it’s even harder

To believe they won’t. Story says other galaxies too many

To count began spinning billions of years ago,

Outsider-art whirligigs, confetti-colored. They

Appear to be melting in the photos.

And every particle continues jetting away

From every other, the edges of the universe

Smoothed flat by hand, like bedspread or tablecloth.

Earlier this morning a bucket bomb

Blew a fireball down the length of a British subway car,

Singeing twenty-two faces. I’d been looking out

A window four-thousand miles away at maple

Leaves beginning to yellow when a bird

Dropped from a branch & drew a straight line

Across my eye. The phone binged—someone we love

Got that doctor news nobody wants. We could

Add the bird’s speed to the other numbers.

Still, I do not feel like I am moving.

O death, you’ve stood me up twice, whispering,

Three’s a charm. It’s impossible to believe things on this planet

Will turn out right. Harder to believe they won’t.

Hours Ago

There is no “distant” or “near” past; it’s all crammed together. If you reach in you’re as likely to come out with a handful of salt from the Atlantic, or King Offa’s dirk, as with whatever you were reaching for—the name of that girl you loved but didn’t tell, the faint tang of father’s sweat when he took off his watch. Or, the PIN number you forgot again, & had to change, hours ago.

Something Sigmund Said

A man in a parachute harness sixty feet in the air, towed by a power boat, thin rope pulling him aloft, liege of the stick figures waving from the dock below, Ahoy, beloveds!—no sound but his own voice and the wind buffing his ears. The unconscious doesn’t believe in its own death, Freud said, doesn’t want to consider how thin the rope, how carabineer or harness may fail. How something, someday, will fail, & against all memory & caution the man once again belong to the sea.

Sehnsucht

Sarah does jigsaw puzzles of the Alps on her iPad. She went to school in the Bernese Oberland, & still dreams the mountains every night. When she moves the pieces she tucks her right thumb between her index and middle fingers, and uses her index to drag the pieces into the puzzle. Only an avalanche or the edge of her hand can clear the town from the mountain, the mountain from the screen. Sarah’s thumb peeks up like the last, topmost piece of the Matterhorn, which, when she places it to complete the image, comes briefly to life. Then, disappears. And she goes on to the next shattered mountain, of which there are thousands.

Two Returns

1

The angel of my better nature has stolen wife, car keys, dog, everything. But the other me will never leave that poor angel alone, will sit by his side until death, whispering in his ear, You know, you know, you know it won’t last—go on, smash it.

2

I was on vacation, following the curvature of the earth. It reminded me I hadn’t been bowling in thirty-five years. It’s very possible I’ll never again go bowling, I thought, and began tacking, with needle & sailcloth, a giant white wing in the sky.

Everyone Was Young

The word Nostrum appeared suddenly on the horizon. It was large & sexual, a gleaming yacht. I stepped onboard & immediately began sinking. It was just a word, after all, but I had loaded it up, with everything. Before my mouth went under I cried out. And was taken & held in the Arms Before Language, that warm & milky sleep.

Poet, playwright, and essayist Jeffrey Skinner was awarded a 2014 Guggenheim Fellowship in Poetry. Skinner’s Guggenheim project involves a conflation of contemporary physics, poetry, and theology. He served as the June, 2015 Artist in Residence at the CERN particle accelerator in Geneva, Switzerland. In 2015 he was awarded one of eight American Academy of Arts & Letters Awards, for exceptional accomplishment in writing.

His most recent prose book, The 6.5 Practices of Moderately Successful Poets, was published to wide attention and acclaim, including a full page positive review in the Sunday New York Times Book Review. His most recent collection of poems, Chance Divine, won the Field Poetry Award, and was published in February 2017. His previous book of poems, Glaciology, was chosen in 2012 as winner in the Crab Orchard Open Poetry Competition, and published by Southern Illinois University press in Fall, 2013. Salmon Poetry, a literary press out of Ireland, will bring out his book I Offer This Container: New & Selected Poems, also in 2017.

Skinner has published five other collections: Late Stars (Wesleyan University Press), A Guide to Forgetting (a winner in the 1987 National Poetry series, chosen by Tess Gallagher, published by Graywolf Press), The Company of Heaven (Pitt Poetry Series), Gender Studies, (Miami University Press), and Salt Water Amnesia (Ausable Press). He has edited two anthologies, Last Call: Poems of Alcoholism, Addiction, and Deliverance; and Passing the Word: Poets and Their Mentors. His numerous chapbooks include Salt Mother, Animal Dad, which was chosen by C.K. Williams for the New York City Center for Book Arts Poetry Competition in 2005. Over the years Skinner’s poems have appeared in most of the country’s premier literary magazines, including The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The Nation, The American Poetry Review, Poetry, FENCE, Bomb, DoubleTake, and The Georgia, Iowa, and Paris Reviews.

Also a playwright, Skinner’s play Down Range had a successful runs in New York City, Chicago, and Harrisburg PA. His play Dream On had its premier production in February of 2007, by the Cardboard Box Collaborative Theatre in Philadelphia. Other of Skinner’s plays have been finalists in the Eugene O’Neill Theater Conference competition, and winners in various play contests.

Skinner’s writing has gathered grants, fellowships, and awards from such sources as the National Endowment for the Arts (1986, & 2006), the Ingram Merrill Foundation, the Howard Foundation, and the state arts agencies of Connecticut, Delaware, and Kentucky. He has been awarded residencies at Yaddo, McDowell, Vermont Studios, and the Fine Arts Center in Provincetown. His work has been featured numerous times on National Public Radio. Skinner served as Poet-in-Residence at the James Merrill House in Stonington, Connecticut, at the Frost House in Franconia, New Hampshire, and for the Arts Festival in Kildare County, Ireland.

He is President of the Board of Directors, and Editorial Consultant, for Sarabande Books, a literary publishing house he cofounded with his wife, poet Sarah Gorham. He taught creative writing and English at The University of Louisville.

Nancy Mitchell is a 2012 Pushcart Prize winner and the author of The Near Surround (Four Way Books, 2002) and Grief Hut (Cervena Barva Press, 2009). Her recent poems appear, or will soon appear, in Poetry Daily, Agni, Washington Square Review, Green Mountains Review, Tar River Poetry, Columbia College Literary Review, and Thrush, among others. She is the co-editor of and contributor to Plume Interviews I,forthcoming in February, 2017. Mitchell teaches at Salisbury University and serves as the Associate Editor of Special Features for Plume.