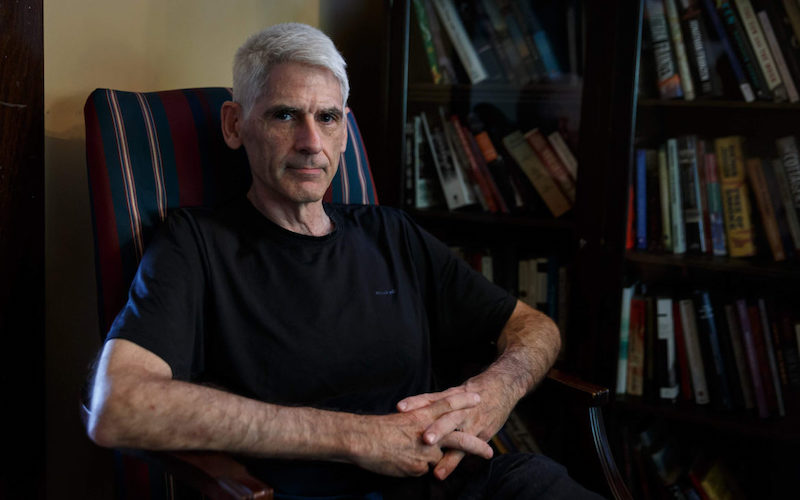

Jim Daniels Interviewed by Amanda Newell

I was delighted to speak with Jim Daniels for this month’s issue about American Patriot, his ongoing collaboration with the photographer Charlee Brodsky—how the project has changed over time, the voices that emerge in the poems, and his love for working across various genres and mediums.

AN: The poems we’re featuring this month are among the latest from your American Patriot collaboration with the photographer Charlee Brodsky. Can you speak to the inception of the project and to your involvement in it?

JD: Our “American Patriot” collaboration focuses on Charlee’s photos of the American flag in different contexts, and my poems in response to them. I think we have a book’s worth of them at this point, and that might be the next step, to try and publish them as a book.

During the run-up to the 2016 election, Charlee started photographing the flag in various places—in particular, working-class communities around Pittsburgh, where we both live. She started sharing them with me, as she did with our other collaborations, and I was really drawn to them for a number of reasons. I’ve always been interested in the role of social class in our literature and our political landscape, and it felt like the stakes were high in this particular election—which, in retrospect, feels like an incredible understatement.

I’ve also been interested in the symbolism of the flag. In other countries, you rarely see people displaying their country’s flag on their homes and cars, etc. Why is it that Americans do it so much, and what does it represent to different people? By photographing the flag in context, Charlee provides hints at what the flag might represent to whoever’s displaying that particular flag, and I kind of ran with the evidence surrounding the flag to try and tell a story.

Another thing I was interested in is faith—in both country and in religion. This whole idea of unquestioning belief which goes against what I see as my role as a writer—to question everything—and the notion that you’re a bad person for questioning the flag/country/God/religion. And of course in many of the photos, religious symbols are mixed in with the flag. Charlee and I both have this curiosity about the world that prompts us to want to dig beneath the surface of any unquestioned symbols, so this particular collaboration has been a very deep and sustaining one.

AN: You mention your previous work with Charlee Brodsky. For more insight about your process with her, readers can check out our 2014 feature, where Nancy Mitchell spoke with you about your “Trace” collaboration: https://plumepoetry.com/featured-selection-trace/

As you point out, American Patriot has been an ongoing project for several years now. Back in February 2017, our friends over at Scoundrel Time published some of the earlier collaborations in this series ( https://scoundreltime.com/american-patriot/ ). That was, of course, fresh in the wake of the 2016 election. I’m curious—how, in your view, has this collaboration evolved since then?

In the earlier collaborations, what’s notable to me is that the flag is truly front and center—perhaps more squarely in focus? In the poems we’re featuring here, the flag is still the central symbol right there at the intersection of race, class, politics and religion, but it’s not necessarily at the visual or textual center of the photos or the poems.

For instance, in the photo that accompanies “On a Personal Level,” the flags are off-center (and of course, the flag to the left is, as the speaker notes, not “the real flag”). In the poem itself, we’re 18 lines in and already in the second stanza by the time the flag is mentioned. I love the moment when the speaker asks, “Is it just me, people,/or is that flag pulling/the whole house crooked, / tilted to the right?”

JD: This is an interesting question. While we don’t consciously think about how the collaboration is shifting over time, I do think it has evolved. Looking back, I feel like the poems have become more overtly political and angry. I remember Charlee commenting on a more recent batch, saying they were edgier, and I think that’s true given my frustrations and feelings of despair as the political situation in our country has become more dire and disturbing.

My head nearly exploded when I saw a picture of the president hug the flag at the CPAC convention. I want the poems and photos to work together not to be shouting or preaching, but trying to deal with the complications of the people who fly the flag and what it means to them.

One of the advantages of this kind of ekphrastic collaborative work is that viewers/readers have the image in front of them, so I don’t have to describe what they’re seeing. And the location of the flag inevitably calls attention to itself, as you note. A bunch of photos of just the flag don’t give me a lot of room to maneuver as a writer, but when they’re part of a larger environment of other things representing the daily lives of the people displaying the flag, it becomes a lot more interesting.

When I bought my house back in 1986, the first time my parents came to visit, my father gave me a flag to display on my porch—it’s part of my background and history. No, I don’t display that flag, but yes, I still have it.

AN: When you say your poems have become more “overtly political and angrier,” even “edgier,” from whose point of view are you speaking? You pretty clearly articulate your own feelings of frustration about the current political situation as it has become “more dire and disturbing,” but I suspect the reasons for your frustration don’t necessarily align with those of the speakers in your poems at least in terms of whom to blame—not that they should. That would be boring. But I’m thinking, for one example, of “Don’t Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One,” where the speaker says, “We’re going some place/where no X’s live.//They stole our flag’s shadow./Said it was a misunderstanding.”

We’ve had something of an ongoing conversation at Plume about the notion that poets should “stay in their lane” when it comes to writing about others whose experiences are different from theirs—both R.T. Smith (https://plumepoetry.com/r-t-smith/) and Amit Majmudar (https://plumepoetry.com/amit-majmudar-interviewed-by-nancy-mitchell/) speak to this in their recent interviews.

So, I’m going to ask you the same question: What is it like to inhabit the various personae in your own poems, and what are the challenges of doing so?

JD: This, of course, is an interesting and sometimes controversial issue, but in general, for me, poets staying in their lane is a pretty boring concept. I mean, the whole idea and stimulation for doing the collaborative work with Charlee is that it takes me out of my lane—my comfort zone—as a poet.

With the flags project, there are no people in any of the photos, so it offers me an easy entrance into the poem as a kind of creative detective—I don’t feel like I’m writing about or coopting others’ experiences. I’m free associating off of what I see and relinquishing a kind of control I typically have in my more autobiographical narrative poems and short stories and films.

When different voices want to emerge, I let them. Also, creating characters, like I do in my various collections of short stories, is something I often do in poetry as well. I get tired of my own voice sometimes, or feel like it’s becoming too predictable. In the latest book of fiction, The Perp Walk, the stories are linked and overlapping, with narrators telling different versions of the same story—it’s up to the reader to decide who’s telling the” truth”—and sometimes I feel like with Charlee’s photos, I’m doing something similar—that the “story” the photo tells is different than the “story” the poem tells. I think it should say something different—otherwise why write the poem at all?

Another aspect of this issue is that, to be honest, I’m not sure my experiences are not that different from theirs—growing up in a working-class neighborhood on the edge of Detroit, these are the people I know and care about. Which brought me into poetry in the first place—that the lives I was surrounded by weren’t showing up in a lot of the poetry I was reading. And when they did, they often felt like caricatures written by outsiders looking in—even when well-meaning, there can be a whiff of condescension that stings me.

I have been the poetry editor for Labor: Studies in Working Class History, since its inception in 2004, and I only pick poems that write about labor from an insider (worker’s) perspective. Can I be sure that all the poets actually had the jobs they’re writing about? Of course not—the poems need to be convincing, regardless of the biographical background of the author—though it turns out that many of the authors are writing about work experiences they’ve had.

So, in three of my earlier books, for example, I have a series of poems about a factory worker named “Digger” in which I write in the second person to enhance a sense of both familiarity and intimacy with the character and permit me to step outside the character as well.

Then, when I began ekphrastic work with Blue Jesus, a collection dominated by poems written in reaction to the painting of Francis Bacon, I first felt the freedom I talk about earlier—like I’m talking in tongues or something at times.

Here’s a list of various approaches I suggest to poets writing in response to visual imagery (and music, which I am doing more and more of, inspired by coediting, R E S P E C T: The Poetry of the Music of Detroit, which will be out by the end of the year):

- Listing, stream-of-consciousness style writing;

- Persona;

- Direct address to a person in the picture;

- Tour guide, or instructional approach—addressing viewers/readers directly

- Pure description;

- Entering the photo or painting;

- Respond to text in images;

- Give your poems an external structure or limitation—a “frame” of sorts;

- Create/imagine your own visual art;

- Collaborate with a visual artist.

I have written poems in response to photos with people in them in both of my collaborative books with Charlee, Street, and From Milltown to Malltown, so I am not adverse to doing so, but with the flags, not having people to write about freed me up to wander a bit more (and, conversely, maybe to bring myself into the poems a bit more at times). It’s challenging and invigorating to take such an internationally known symbol (the American flag) and mess with it.

I’m not so much interested in blame—that also can make for an easy poem. You’re not risking anything by shooting at a target unless maybe your own picture is on that target. There’s of course that old adage, “write about what you know,” but I feel that should be “write about what you don’t know about what you know.” You’ve got a certain knowledge and interest in a subject that prompts exploration and discovery rather than creating stereotypes, etc.

I guess what I’m saying, finally, is that I don’t think much about the challenges of taking on these personae. Many of them feel like putting on an old glove. For me, Charlee’s photos provide a lot of memory triggers, even though we’re looking at Western Pennsylvania towns, not Detroit.

Sure, I can get things wrong. But when I’m working on a series, that also doesn’t bother me so much. I feel like if the poems play off of each other—and I’m hoping someone might want to publish a book of these at some point—then that creates its own tension and dynamic. It allows an inconsistency that creates (I hope) (sometimes) a greater degree of authenticity.

Because none of us, finally, stay in our lanes forever. We’ve all got the secret streams, the underground rivers—it’s a matter of whether we let them emerge or not. I believe part of a poet’s job is to allow them to emerge, and Charlee’s photos do that for me. I don’t think too much about why they do. I just feel very lucky to have partnered with someone who takes me into territory that is both familiar and new.

AN: I love that idea—of entering territory that’s “both familiar and new.” A kind of wandering, isn’t it? Or, dare I say, trespassing? The notion of ownership—of who gets to lay claim to what—is one question poems like “Yes, Trespassing,” ask us to “wander” about. In it, the speaker notes:

This too is America, I know,

414, and your neighbor 416

who’s sick of living next door

to your heap of—hey, can you

at least pull the weeds? Is it

trespassing or wandering

or stupidity that makes me want

to walk through the open gate

and into the darkness

that sure as hell ain’t no Eden?

America’s got a cellar, sure,

well-vented for the stench.

I think I’m beginning to read “Yes, Trespassing” as a kind of ars poetica, too, about the creative process, itself! But you do seem to like to cross boundaries—maybe collapsing them would be a better way to describe it. You mention, for example, how you work across genres and mediums—in addition to poetry, you write short stories and produce films, you’re responding to both art and music in your writing. So I’m wondering/wandering if your subjects immediately strike you as better suited for poetry, story, or film? How do you make that decision?

JD: Yes, I suppose I’ve been a trespasser from way back, given my Catholic upbringing—“forgive us our trespasses…”. That’s a good question about genre. I kind of borrow from myself at times, so many of the same or similar images and stories show up in more than one genre. The most recent film, “The End of Blessings,” is based on a poem—I may have said this already, so if I contradict myself, well, see Walt Whitman on contradicting oneself…

You can watch the film here: https://vimeo.com/johnricefilms/eob

Two of the other films were based on the title stories of two of my books of short stories, No Pets, and Mr. Pleasant. The fourth film was originally a one-act play, Dumpster. I don’t decide on form right away—between fiction and poetry—but it evolves pretty quickly. If something requires a lot of dialogue and more than one central character, it’s going to probably end up as a story.

In The Perp Walk, the latest book of stories, I alternate prose poems/flash fiction with more traditional stories, so there’s some blending going on too. I do a lot of tinkering in the revision process, as most writers do, and it’s fun to see how that changes things, and sometimes results in a story and a poem. One example that comes to mind is this sort of touchstone image from my childhood: our local movie theater closed down, and on the marquee, they left “CLOSED FOR REPAIRS” up, though they never reopened.

So, the kids in the neighborhood took to throwing rocks at the marquee to knock off letters, one by one (the marquee had two sides, so there were a lot of letters to take aim at). I had a good friend we called The Big O, and an O was the last letter up there. We were hanging out, wandering the streets together—young teenagers, too young to drive—and I knocked that O down and gave it to him. It was such a sharp image that I wanted to use it more than once, so it shows up in a story and in at least one poem.

The movie theater ended up becoming a chain drugstore, and in a story I’m working on, it shows up again. And, going full circle, that focus on place in my writing—on the Detroit area—is another thing that connects me to Charlee’s work. Her photos are often series focused on one place, and they evoke such a strong sense of that place, I’m pulled in. Like I said earlier, I think, the places she focuses on tend to be familiar to me due to social class, etc.

AN: Should we expect a film on The Big O? I just watched The End Of Blessings, which was widely praised upon its premiere in 2015. I found myself looking for the number on the old Italian couple’s house—I was waiting for a flag to appear!

Interesting, too, to see how the idea of staying in one’s lane—or not, and the ways in which we make ourselves vulnerable when do we do step out of it—plays out as we follow the cyclist on his weekly rides. You can definitely see the intersection of class, race, faith, and place, which themes are present in so much of your other work and in this latest collaboration with Charlee. But I digress—

One last question. You’ve spoken already about some of the other projects you’re currently working on, but I’m also curious: What are you reading these days?

JD: Actually, that would make a good movie scene, I think, but it’d be too expensive to shoot, creating the broken marquee, etc. My films tend to be pretty low budget! Even as I write this, I remember shuffling through the broken glass or plastic or whatever it was that fell when the rocks landed in front of the Ryan Theater.

I at this very moment am reading three books, Hanif Abdurraquib’s nonfiction book, Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to a Tribe Called Quest, which is right up my alley, combining music and personal memories, and two writers whose work I have always admired, Amy Hempel’s latest book of short stories, Sing to It, and Karen Russell’s new book of stories, Orange World.

I also just finished a great memoir by a former student of mine, Cameron Dezen Hammond, This is My Body: A Memoir of Religious and Romantic Obsession, and have just started reading Patricia Jabbeh Wesley’s Praise Song for My Children: New and Selected Poems, that I will be blurbing. Kind of random, I suppose—my reading tends to be that way!

On a Personal Level

I have tossed massive truck axles onto pallets

at the end of the assembly line, Ford Sterling

Axle, down Mound Road seven miles

from the Motor City. Huh (lift)/ Ugh (toss)

alternating with another guy to allow

a few seconds of human recovery time,

though at the end of my early shifts

my arms tingled and ached with numb

strings of sweat as I wobbled toward

the time clock. What I want to say

is I lived in a little house like this

at the time: grungy pale green siding

with aluminum awnings that would never

be white again due to the nature

of the air from factories like mine.

Why bother scrubbing?

On a universal level, how about

that flag? Nobody laying on that

pallet. You could be crucified on it,

and I believe a few people have,

while the rest of us were busy

carving tree stumps into cute

little bears. How much power

does it take to keep it upright

and useless, some odd compromise

with sacrilege not to toss axles

or bags of fertilizer or mysterious boxes

on it when tossing things on the damn

pallet is supposed to be All-American

in the first place. Why bother

scrubbing, I guess I am asking.

The bear looks lonely

or constipated from this distance,

the real flag to the right, a little

ragtag, ridden hard, out

of breath against the perfect

fake shutters next door.

Is it just me, people,

or is that flag pulling

the whole house crooked,

tilted to the right? I try

not to read too much into

things. Er—I mean, that’s all

I do is read into things. So,

when your gutters don’t connect

which came first, the pallet

or the flag? I lived in a house

like this. The guy I alternated with

took extra axles when I first started

to give me more of a breather.

We didn’t talk about it

and he didn’t expect any favors

back. I don’t think anyone

ever noticed. The steel pallet

grease-infused, though

looking back on a personal level,

somewhere beneath the grease,

that pallet was red, white, and blue.

Huh (lift)/ Ugh (toss).

Feel free to make fun of the bear.

Why bother scrubbing?

Yes, Trespassing

I’ve been thinking a lot about trespassing

lately. When does wandering turn bad?

I have never gotten a citation for wandering.

Wander a mile in my shoe. The other shoe

dropped. I’m wandering into that flower box

and remembering the bright scent—

of betrayal? A turn

for the worst. Who knew turning up

the volume would crack the cement?

Bad flowers! Painting the steps

always a bad idea. Never paint

your steps.

If the flag is the brightest thing

in your window box, you’re screwed.

Oh, I’m full of the wisdom

of the I told you so’s

and the already damned.

This too is America, I know,

414, and your neighbor 416

who’s sick of living next door

to your heap of—hey, can you

at least pull the weeds? Is it

trespassing or wandering

or stupidity that makes me want

to walk through the open gate

and into the darkness

that sure as hell ain’t no Eden?

America’s got a cellar, sure,

well-vented for the stench.

What’s that saying about not

wanting to see what goes on

in the sausage factory?

It’s cleverer than that.

Cleverness has no business

being in the basement of 414.

I’ve been wandering a lot

about thinking, lately. Like,

it is okay to kneel for the anthem

if Aretha is singing it?

Must be the fumes getting to me

out those vents. I’ve got a weakness

for reggae and redemption.

God must get pretty tired

of blessing us. Or dealing

with the clowns who imagine

they have the authority

to speak in his name.

I’ve spent my life trespassing.

I’ve carried the cross

and I’ve carried the flag

and I’ve carried the fire

and I’ve carried the water

and I just want to rest my weary soul

on the steps of 414. Yeah, I see the tools

on the porch, and I know there’s work

to be done. It don’t much matter

if those are scrapers or weeders

or paint brushes up there

with that 5-gallon bucket of primer.

414, that’s a start. I understand,

Americans being big on numbers.

That shoe,

it looks just my size.

Don’t Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One

The brick garden was doing just fine

until X moved into the neighborhood.

Yeah, we’re moving out. Not

surrendering, we’re just giving up

in the great American tradition.

If you love your country

you’ll buy my house.

Flag included.

Wave proudly.

A rare Siamese Twin flag.

For luck.

Don’t worry about the X’s.

Oh, you’re X too?

I just thought. Nevermind.

You’ll need it, the luck.

Shoulda known

bricks don’t grow

in this kind of weather.

That’s why the sign’s up high.

Keep from catching

what the bricks caught.

That’s why the flag’s higher.

An arm’s length can kill you.

We’re going some place

where no X’s live.

They stole our flag’s shadow.

Said it was a misunderstanding,

We’re taking

every one of them bricks

to our new glass house.

The boy’s out back

loosening up his arm.

Plume was also curious about the photographer Charlee Brodsky’s thoughts about American Patriot, so we asked her to comment, as well.

CB: Over a fortuitous lunch over ten years ago, Jim and I discovered that we shared values and interests—and although our tools are different, he uses words and I use a camera, we both create images of life in the rust belt. Our most recent project, American Patriot, took a few years to make and our other projects, too, were years in the making. We work in tandem sending poems and images back and forth, and meeting from time to time to look at poem/image combinations together. We are energized by each other’s observations.

Regarding American Patriot specifically and my work more generally, it takes me a while to understand what’s at the core of my photographs, and I make a lot of bad pics in-between the few that I like. Jim is helpful there. He’s my outside “reader.” He helps me see my work. When I might be too fixated on a misplaced shape or detail, Jim instinctively senses that he can find meaning, not in all the photos that I show him, but in the ones that he carefully chooses to work with. Working with such an astute colleague, I see through another set of eyes—I learn from seeing how Jim reads my images and what he creates from them.

I started photographing the American flag in Pittsburgh neighborhoods and towns in Western Pennsylvania during the 2016 primary season and there were a lot of them dotting lawns, projecting from front porches, and affixed to storefront windows.

I wanted to understand how this region that was once thoroughly blue had turned red. I showed a stack of these photographs to Jim and, fortunately, he embraced the project. As with our other work, we strove for conversations between his words and my images. When we are successful, we are rewarded by seeing our work meld into one voice telling many stories.

Jim Daniels is the author of seventeen poetry books, including, most recently, Rowing Inland and Street Calligraphy, 2017, and The Middle Ages, 2018. He is the author of six collections of fiction, four produced screenplays, and has edited six anthologies, including Challenges to the Dream: The Best of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Day Writing Awards, a competition for high school and college students that he founded in 1999. His latest collection of short fiction, The Perp Walk, was published by Michigan State University Press in 2019, and his coedited anthology, R E S P E C T: The Poetry of Detroit Music is forthcoming later this year. His poems accompanying the photographs of Charlee Brodsky have been displayed in many art galleries and collected in two books. During his long career, he has read as the warm-up for Lucinda Williams at the Three Rivers Arts Festival and on Prairie Home Companion, had his poem “Factory Love” is displayed on the roof of a racecar, and sent poetry to the moon as part of the Moon Arts Project. Honors and awards include the Tillie Olsen Prize, the Brittingham Prize, the Milton Kessler Poetry Prize, two grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, and many others. He is the Thomas S. Baker University Professor of English at Carnegie Mellon University.

Charlee Brodsky, a fine art documentary photographer and a professor of photography at Carnegie Mellon University, describes her work as dealing with social issues and beauty. In 2012 she was honored to be Pittsburgh’s Artist of the Year chosen by Pittsburgh Center for the Arts. A selection of her awards includes the Tillie Olsen Award with writer Jim Daniels for their book, Street; an Emmy with the film team that created the documentary, Stephanie, which is based on her friend’s life with breast cancer; the Pearl of Hope award given by Sojourner House for her work with her students in the Pittsburgh community; and Pennsylvania Council on the Arts fellowships. Her work is widely exhibited and published.

Charlee Brodsky, a fine art documentary photographer and a professor of photography at Carnegie Mellon University, describes her work as dealing with social issues and beauty. In 2012 she was honored to be Pittsburgh’s Artist of the Year chosen by Pittsburgh Center for the Arts. A selection of her awards includes the Tillie Olsen Award with writer Jim Daniels for their book, Street; an Emmy with the film team that created the documentary, Stephanie, which is based on her friend’s life with breast cancer; the Pearl of Hope award given by Sojourner House for her work with her students in the Pittsburgh community; and Pennsylvania Council on the Arts fellowships. Her work is widely exhibited and published.