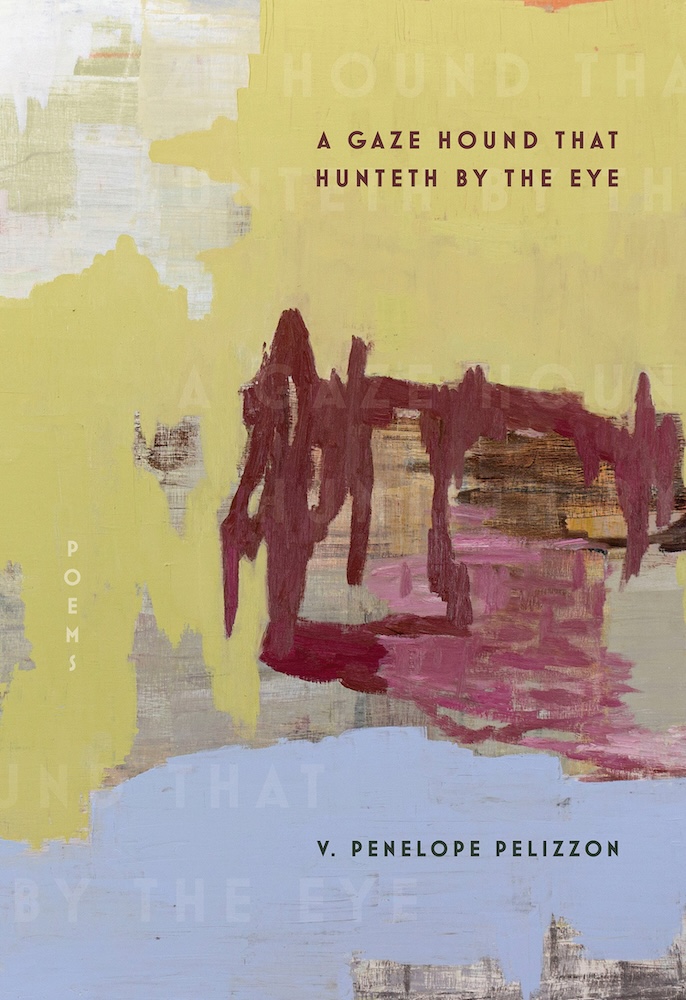

review of A Gaze Hound that Hunteth by the Eye.

Pitt Poetry Series, University of Pittsburgh Press.

published February 2024. 100 pages. $18.

Were I not smitten, ahead of time, with V. Penelope Pelizzon’s poems, I might have passed over her newest collection, deterred by the old-fashioned verb-ending and dubious about the fanciful species for which the book is named: A Gaze Hound that Hunteth by the Eye. Let that be a lesson to me. In fact, let this whole book be a lesson to me.

The book’s title poem, which first appeared in Plume, is also its first poem, and holds, exquisitely, so much of what this collection is and does, though it begins as a defense. Specifically, the speaker, a 16th-century woman whose affection for her lapdog earns the scorn of William Harrison, Vicar of Wimbish, objects: “It isn’t criminal.” But she is only on her heels for a moment before she begins reeling off the crimes of men by way of contrast—“it isn’t sodomy / or taking horses to Scotland / or poaching the king’s deer”—and then she embraces the white magic of her “witchcraft.” Soon there is glee in her voice, and resistance and brilliance:

He’s better off dead, not here

forced to catalogue how, today,

I climbed off my broomstick

and smooched my leashed familiar

shamelessly on her damp nose, taking her

along to weed my pandemic victory

garden.

The shamelessness expands. For instance, when the speaker announces “Last night I bedded / King Richard II, / book on my belly,” it isn’t the playwright cuckolding Harrison, though it’s from his tome, Hollinshed’s Chronicles, that “Shakespeare will pinch from to flesh out / his kings.” Rather, the woman who lends this poem her voice does the “bedding.” As for Shakespeare, he is an honorary woman, in whose “uterus / of a mind the chronicles / seeded this fruit.” I suppose that makes Harrison an unwitting sperm donor.

The writer, though, having flouted the conventions of gender and victory gardens (“true victory / gardens grow human food”), doesn’t rest there. The poem broadens still more, asking

Who’s fit

to govern the garden of

the state? Flinchless, the first Elizabeth

dead-headed traitors and shut plaguey stages

but she had, I recall, the heart

and stomach of a man.

She left no issue but art

breastfed on the rich milks of empire

her ships ploughed the sea to reach. Settlers came here

and native people not yet sick

taught them about dying

cloth blue with false indigo.

So, beginning with a lapdog, the poem conjures childlessness and mortality, colonialism and botany and plague. Like the book that shares its name, “A Gaze Hound that Hunteth by the Eye” opens and opens, and its expansiveness occurs by way of metaphors and allusions so deftly handled that they feel like free association. Really, though, they are art and intellect, incredible craft.

In many ways, then, this book’s title poem is a capsule for the whole. That is, this writer’s new collection has breadth and heft because of its subjects: a difficult mother, a difficult infertility, varieties of home and foreignness. But its profundity comes from the poet’s peculiar, transporting sense of scale—because of the way Pelizzon navigates time and space. Put simply, her poems telescope and swoop. And by shaking the reader (and, I suspect, the writer) free from linear chronology and familiar terrain, they make reckoning with the world and ourselves feel not only possible, but necessary. As no doubt it is.

Most pointedly, these poems’ reach, back in time and across countries’ borders, reveal human truths that persist on every continent, in every century, sometimes writ large, sometimes in the smallest fonts. Take the long poem “Animals & Instruments.” In it, the speaker makes her way from the “calligraphed name / Suleiman the Magnificent,” its

letters […]

crisp as pennons unfurling in their gallop

west across the vellum, just at the Ottoman vowed

he’d sweep, erasing infidels . . .

to her parents’ autographs in her DNA, not to be inherited by the children she could not bear:

Centuries of migrants, their signatures

Xed inside the cells passed down to me

by those two travelers

whose hands I’d held so briefly, had reached

their final port.

That shift in scope, from a sultan’s empire, too vast to see across, to a human ovum, just visible to the naked eye, is staggering, as is the five-hundred-year leap Pelizzon executes to yoke them. But cupped in the trope of penmanship, there her theme is, if in wildly different magnitudes: conquest, our longing to birth something that will survive us. A significant subject, to be sure, but the poem’s almost dizzying shifts in dimension are what bring it into focus, its vertigo triggering a form of revelation.

Elsewhere, Pelizzon uses her long reach and quick pivot to reckon with the privilege on which so much of art and welcome depend. In “The Soote Season,” she muses:

What hunger led the first hominid to feed

scarce meat to a wolf and thereby nurture

trust attuned to our every gesture

more fully that we trust our species?

Before he’d rent to me my landlord insisted

we Skype to ascertain, it dawned on me[,]

[…] that I was a person

sinecured and stable, and unsable.

The apartment is sunny and affordable.

I signed the lease. The dog does his business.

Again, the scope of the poem—it pans from the first hominid to a racist landlord on Skype—disorients us into noticing the old, old thing we have not evolved our way out of: distrust for each other. Another transposition is at work here, too. Earlier in the poem, as she traverses a park, noting Jamaican nannies and the “small white babies” in their care, the speaker tells us “I am / a gaze hound that hunteth by the eye.” Leaping across species, in other words, she recasts herself as a dog and anticipates the parallel sentences “I signed the lease” and “The dog does his business,” reframing the line so that it shimmers with self-judgment.

That said, not every reorientation that A Gaze Hound shakes loose from time or geography unfolds so dramatically. Some take place across only a generation, as in the poem “Of Vinegar Of Pearl”:

And what are tears

but mirrors? I found penciled in my mother’s high school Lear.

Now I reflect on her. In my pocket

compact dabbing on lipstick, it’s

her sneer I gloss.

This poem’s smaller canvas notwithstanding, here too we see time fold: the daughter old enough to remember her mother at the same age, old enough to recognize a likeness between them. Thus, the admission “it’s / her sneer I gloss” signals a rift that the daughter preserves, glossing her mother, interpreting her from some distance. But of course “it’s / her sneer I gloss” also collapses whatever separates mother and daughter, insisting on the selfsame curve of their lips. Moreover, to “reflect on her” mother, the speaker must look past the edge of her own lifetime, into her “mother’s high school Lear,” but from the reflection of the older woman’s marginalia—“And what are tears / but mirrors?”—its reversal ricochets into the present: “And what are mirrors but tears?” And all of this—mirror, Lear, tears, lipstick, mother—fits in Pelizzon’s “pocket / compact.”

Often, teachers describe poetry as the art of compression, and the poems in A Gaze Hound that Hunteth by the Eye might help them make their case. Look how much a line break does, set between “taught them about dying” and “cloth blue with false indigo” in the description of the indigenous people British settlers displaced. Look at the coinage “unsable,” the prejudices it imports into “The Soote Season.” Or the word “gloss” an its double meaning.

But compression connotes a magician’s scarves tightly wadded up a sleeve or the density of a fruitcake, and Pelizzon’s writing never feels so cramped or heavy. Sure, the poet cups farflung ages and places in her hands. But this collection has more in common with the perennial gardens with which it begins and ends, its beauty the sort that opens outward and proliferates, sowing itself. echoing across years.