Carnegie Mellon University Press

2020

$15.95

78pp. paper

ISBN 978-0-88748-861-6

Joyce Peseroff has been a personal friend since she served as Ploughshares’s poetry editor and managing editor. Her first collection, The Hardness Scale (1977), had just come out. She edited The Ploughshares Poetry Reader as well as her own issue, enlisted Donald Hall to guest edit and worked with Seamus Heaney on two issues. She left Ploughshares before the birth of her daughter; then taught at Emerson, and later at U. Mass., Boston, where she directed the creative writing M.F.A. program.

That said, here is her crowning, sixth collection, Petition, a witty, aging, suburban woman’s contemplation of passages, future shock, body, long marriage, parenting, and friendships; an examination of social conscience; a soul’s self-standing, its reconciliations, and insatiable yearning.

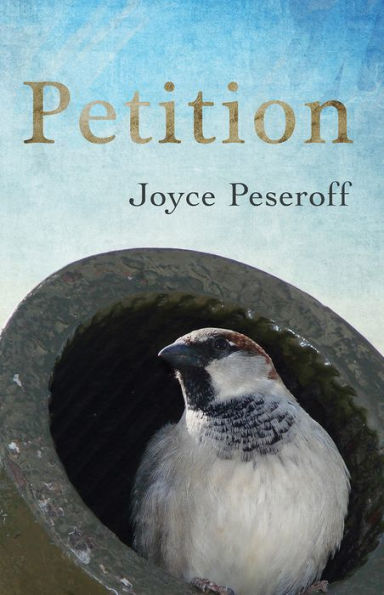

The cover photograph alludes to this array of themes. A sparrow perches in a cannon’s mouth, perhaps even nests there. The cannon suggests both past and future destruction, while the sparrow seems vulnerable and oblivious.

Petition’s opener, the title poem, invites comparison to Richard Wilbur’s “Advice to a Prophet,” invoking our responsibility as tenants on the planet. Where Wilbur advises the prophet to alarm us with the loss of metaphorical ground (“all we mean or hope to mean”), Peseroff confesses to the Creator and begs for a second chance: “Give us eternity again, we’ll set things right.” The tone here implies her self-dismissive, weary head-shake, “Sure we will.”

In “Not Far,” she considers news of evils, close and remote from the speaker’s front porch: a nearby prison, bomb strikes and civilian deaths in the middle east, a derelict in a riverbank shed, Trayvon Martin shot on his way home by police, and in Manhattan “rats [chasing] rats upstairs” in a gilded tower like Trump’s. In “For the Stranger,” a white woman has her routine interrupted by another woman outside a nail salon, who asks to be driven home; and torn between charity and warnings against strangers, the speaker concedes, but feels “timid…as if to summarize my life.” The speaker of “Receipt,” however, feels unafraid to return a sweater without a receipt, while fully aware that a black man wouldn’t dare to leave Sears with socks in his hand rather than a plastic bag. A daughter rebels and comes of age in “Astronauts,” yet is tethered at an orbit’s distance. Other poems touch on jury duty, the O.J. Simpson trial, memories of 1950’s “old terrors…succeeded by new,” border arrests of migrants, the hitch-hiking robot beheaded in Philadelphia (“open road…didn’t work. True for humans too”). This section ends with “Egg,” where the speaker has been lured to try six months in Florida and is cleaning her fridge before returning North. Finding one egg, she meditates on Mandelstam’s eating a rare egg offered by Akhmatova before he is taken away by Stalin’s secret police; on never knowing the future; and on saving food for the starving—but drops the egg into the disposal. She is troubled but at the same time dismisses conscience: “who could have dreamed this future” of a homeless derelict camping nearby, yet “what could one egg do to redeem it”?

The book’s middle section probes the speaker’s loneliness, losses, and mortality. Beginning with a return to Jane Kenyon and Donald Hall’s farm and its quaint town (“The High Trees”) , she remarks on missing them twenty years after their deaths: “Jane’s brother pointed, look how high the trees above their grave have grown.” In “Missing Hiker…,” she identifies with a woman who died alone and communicated her ordeal in a notebook, much as the speaker is doing in these poems: “Can I understand the pain of others only by suffering, which I hate?” In “Ghost Story,” where the speaker is given a photo of her husband Jeff “kissing another woman five years before we met,” she wonders “what happens after I die?” Then dourly imagines him as a widower reheating beef stew and living with “a woman who ferments her own cabbage and beer.” “Let’s let the nub of our bitterness go,” she writes in “The Thaw.” She speaks from Florida to the “you” in New England in “Snowbird Song”—“a faraway love I touch/ through wireless ether”—who holds his phone out his car window so she can hear the sounds of spring. She muses about customs in Japan, where “you can hire a family if your wife has died and your daughter won’t speak to you” (“Lonely in Japan”). She tries to help a depressed friend (“La Casa Bellina”)—“I held your hand/ in coffee shops”—but can only summon a vision of their swaggering forward together, “throwing silver as we go.” In “Sonnet on the Solstice,” her loves are her husband and daughter: “overwhelmed by love’s bright light, who sees a thing?” She is balefully comic in “On Choosing One’s Manner of Death,” at first echoing Dorothy Parker, then recounting the story—“or was it a joke?—of a wise man captured and given a choice of deaths by Kahn, replying “old age.” Thinking again of Jane and Don (“Coins for the Boatman”), she moves from hard-case slang—“spare me a March stroked out in the ICU / followed by years on a vent farm” to the poignant and vulnerable, “What I’ll feel for Jeff and Liz, I’m glad I won’t have a body to feel.”

The poems in the final section highlight reconciliation, choices, and wistful good humor. “Dear Thirst” plays with fact and meaning, physicality and spirit, body and soul, life and death, ground and metaphor: “before / desire, the planet was no / gorgeous world.” We’re invited to fellowship, where “we’ll laugh at rogues, set the world at rights” (“After Horace”). In “Ending with the Corpse Pose,” we laugh at ourselves as we “pitch and roll like mermaids,” as “we’re / old, that junk in the trunk / packed like our basements” and exhorted to “be the flood / tide before a full moon. It’s / the moon you want, after all.” Property you can’t take with you includes an Oriental rug and “brown furniture” (“Heriz”); custom hiking boots that you hide from Good Will, “not ready to admit that choices narrow” (“A Pair of Hiking Boots”); or someone else’s lived loss or discard (“Boot Found on the Side of the Road”). The speaker mocks warnings, personal impossibilities, and choices as well, shading examples from frivolous to grave, such as “trust in the soul” (“A) Don’t Do B) Can’t Do C) Won’t Do”). She sees “Turkeys in Twilight” as “widows…marching, / protesting war or pension cuts / or the bridge collapse // that plucked them from their toms” and also as wild, disappearing into conservation land. In the closing poem, she imagines a blind man regaining sight, but preferring darkness “to looming abstractions / accelerating past,” and choosing blindness again, where he can “sit / next to the demented woman….and hold her hand / as long as it needs to be held” (“Irish Music”).

What great company this lived life’s poetry is! In keeping their delicate balance, Joyce Peseroff’s poems are honest and demanding; Tolstoyan in embrace.