Sven Birkerts examines Mark Strand’s poem “The End” in this month’s essay for Plume with a surprisingly sudden awareness of its “personal “message,” the type that comes to him, he confesses, “obliquely, and serendipitously.” “There is knowing and there is knowing,” he asserts somewhat mystically about poems that “reveal themselves” suddenly long after one has read them. “The End” is such a poem for Birkerts. “How could I say I knew this poet’s work,” he writes with a sense of shock, “if I came upon this poem, as I recently did, and felt it as a revelation. Where were the lines all these years that I didn’t know them? As with kinds of knowing, there are kinds of readiness. Maybe the person I was years ago did know the poem, maybe I slowly moved away from him. A simpler way to say this might be: I’ve gotten older.” Birkerts melds self-affrighting revelation with deft analysis in his reading of Strand’s Pslam-like poem, accomplishing what only the most deft readers express in their critiques of enduring poems and fiction, namely, an exegetical prose that is as enlightened and economical as the poems they’re writing about.

–Chard DeNiord

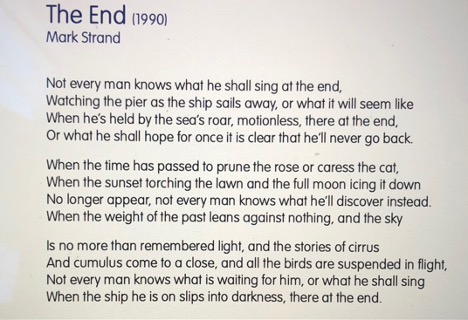

I don’t know why this should be, but I find that many important things—I think of them as personal messages—come to me obliquely. And serendipitously, as did this poem, “The End,” by Mark Strand.

I have read, and even reviewed, Strand’s work over the years, but my encounter with “The End” confirms yet again that there is knowing and knowing. How could I say I knew this poet’s work if I came upon this poem, as I recently did, and felt it as a revelation. Where were the lines all these years that I didn’t know them? As with kinds of knowing, there are kinds of readiness. Maybe the person I was years ago did know the poem, maybe I slowly moved away from him. A simpler way to say this might be: I’ve gotten older.

I came upon Strand’s poem by way of a photography book, Remembered Light: Cy Twombly in Lexington by Sally Mann. I have liked much of Mann’s work, and when I saw the narrow spine in a used book shop, I pounced. The title compelled me, combining as it did two abstractions that are special keywords for me—memory and light. I had no idea they were taken from the poem by Strand, until I read the first paragraph of Simon Schama’s introduction, in which he writes, with faux bluster: “Her title is torn from a beautiful but mercilessly dry-eyed time’s-up-fellas poem called ‘The End’ by Mark Strand.” He then quotes these two lines: ”When the weight of the past leads against nothing, and the sky/ is no more than remembered light…”

That was the point of the dart that found me. It seemed just then that I had read nothing quite so poignant, and when I went to find the poem, I felt it all the way through. Auden proposed that images should “hurt and connect,” and these did—visually, tonally, and with a deep sense of weathered sorrow.

Poems really only exist in the space of the private encounter. The poet’s words arrive through the scrim of the reader’s sensibility, which is, of course, dense and private past all accounting. I have no doubt that “The End” reached me because I am older and think more and more about so-called “last things.” The title itself put me on alert, and when I listened the music carried me start to finish—a music that contradicts any assertion of dry-eyed mercilessness.

~

The poem is unique in the core way that great poems are unique, but

I do also hear voices of other poets contributing harmonic notes in each of these three stanzas. First, I feel that I recognize a moment from Cavafy’s “The God Abandons Anthony” in the opening lines—something about the voices, the music, and the impression of an inexorable recession:

listen—your final delectation—to the voices,

to the exquisite music of that strange procession,

and say goodbye to her, to the Alexandria you are losing.

The dock recedes just as Anthony’s Alexandria does—slowly, with the heightened effect that slowness creates, and a growing sense of magnitude.

Then the opening of the second stanza—how not hear “East Coker”—indeed the whole of the Four Quartets—recalling, if subtly, Eliot’s preoccupation with time, light, and, of course, last things:

Houses live and die: there is a time for building

And a time for living and for generation

And a time for wind to break the loosened pane…

I find yet another of these ghostly harmonics in the third stanza, where I can’t not pick up traces of Derek Walcott’s “The Season of Phantasmal Things,” yet another lyric valediction:

Then all the nations of birds lifted together

the huge net of the shadows of this earth

in multitudinous dialects, twittering tongues,

stitching and crossing it.

And a few lines further on:

…the birds’ cries soundless until

There was no longer dusk, or season, decline, or weather,

Only this passage of phantasmal light

That not the narrowest shadow dared to sever.

~

For me, the vibrations are there in each stanza, but “The End” is in no way a patchwork of influences. The poem gestures homage, no question, but at the same time it stands entirely free—in the purity of its unfaltering arc, the perfect pitch of its diction, and a resulting wholeness embodying a recognition of anticipated loss that is already on the far side of sorrow.

The poem comes my way at the most recent stage of my musing on just these things. What feels new, personally hard-won, is a sense of the scales drawing up even, beauty and death.

At this point, I realize, I could start citing poets and poems and never be done with it.