Miho Nonaka

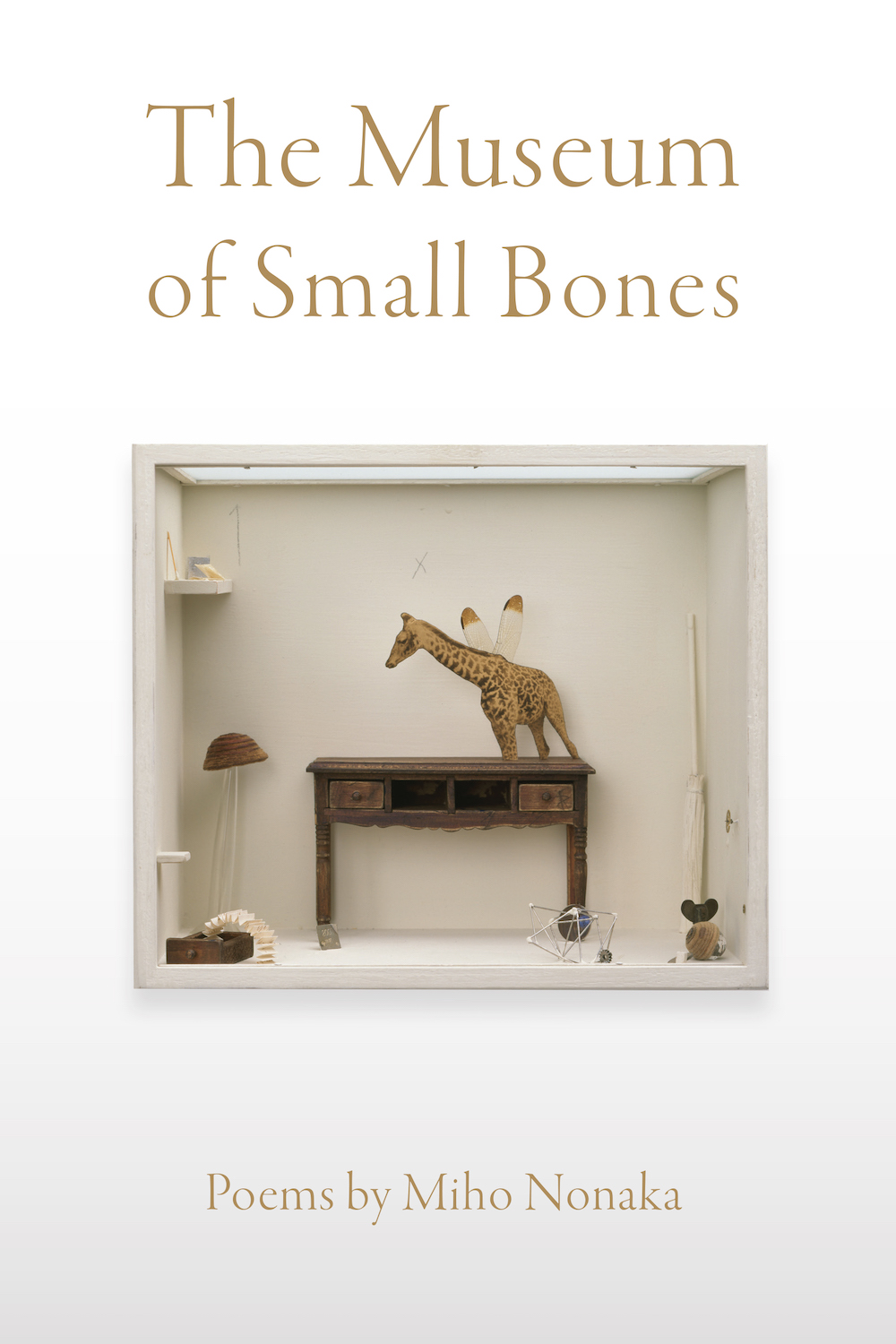

The Museum of Small Bones.

“2020”

Ashland Poetry Press.

$19.95, paperback. 82 pages.

Reviewed by Chelsea Wagenaar

“I dreamed of a power // to make small, imperceptible things / perceptible,” Nonaka writes in the title poem, “like the pattern of bones of a bat / in flight. The power to stave off our despair.” These lines wonderfully illustrate the quality of keen attention Nonaka brings to the world around her. Each poem testifies to her ability to gently, generously describe a small thing: “peas…hissing in the pan,” “a speckled conch,” “the Madonna’s berry-blood eyes,” the “glass eyes” of a doll, with “a lilac flame in each iris.” The attention to the small, I think, is indeed a “power to stave off our despair” – an aesthetic sensibility that brings to mind Edmund Burke’s thoughts on beautiful, small objects:

“There is a wide difference between admiration and love. The sublime, which is the cause of the former, always dwells on great objects, and terrible; the latter on small ones, and pleasing; we submit to what we admire, but we love what submits to us.” (from A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful, 1756)

Nonaka’s poems, however, are not so simply attending to the “small” because of a need to demand submission and stake out power. Rather, The Museum of Small Bones demonstrates ways in which the “small” actually may demand our submission to it; her poems invite us to scrutinize how we uncritically assume positions of power over smallness in ways that, ultimately, reveal only our own thinking to be small.

This is especially on display in the beating heart of the collection, an astonishing series of thirty prose poems collectively entitled “Production of Silk.” This series boasts many virtues: Nonaka’s narrative patience, careful discursiveness, her wide range of tonal registers, and her ability to sustain and develop complex ideas.

The series opens with “Heavenly Worm” and ends with the poem “If I Were,” a set of bookends that serve to nicely illuminate the subtle self-portraiture at work in the prose poems. The poems pull together many strands: childhood narrative, encyclopedic description of the silkworm’s life, excerpts from early Japanese poetry about silk production, scenes from writing workshops, and meditation on the way we talk about the body. Together, the poems unfold a thoughtful, unique way of considering the production of beauty. What makes a thing beautiful? Is beauty “made”? And what is the cost of beauty?

The first prose poem begins in an elementary classroom, with Mrs. Ito teaching the Japanese character for “silkworm” and commissioning each of her fourth graders to care for five silkworms: “To feed these dark babies, you must first julienne your mulberry leaves.” Unexpectedly, then, the second poem in the series verges sharply away from the first classroom scene into another. Called “Cowboys 1,” it narrates the speaker’s experience of having her silkworm poem workshopped by a celebrity American poet, “Cowboy X,” who dismissively pronounces the poem not a poem because he doesn’t “believe any of it for a second.” Nonaka proceeds, throughout the series, to parallel the art of caring for silkworms with the art of poetry as an undertaking of equal mystery, rigor, and painstaking care, both processes often plagued with futility. In “Feast,” she writes of her two silkworms who “shriveled up,” while the other three, “as soon as I put the shreds of washed mulberry leaves into their paper home…would start gorging.” And yet despite the inevitable risk of futility, Nonaka shows the ennobling—but also alienating—status conferred upon those involved in silk production:

“I read somewhere that in southwest Nigeria, Yoruba men are forbidden to spend the night with the women engaged in spinning silk for the season…No stranger is welcome in the house. You wear simple, clean clothes, and abstain from smoking, drinking, putting on makeup, and eating garlic…Raising silkworms and extracting their silk is a sacred project, and you must consecrate yourself as such.”

Raising silkworms and extracting their silk is also, in Nonaka’s work, a metaphor for translation, one of the collection’s main themes. The silkworm translates mulberry leaves, by its body, into “a thread, a precise mixture of proteins that hardens into a fiber once exposed to air…each fiber is triangular in shape, refracting light.” Writing itself is an act of translation—how one navigates “the gap between language and life”—and Nonaka finds herself, as a bilingual poet, poised always in between two languages, herself a medium, a sieve, a silkworm.

She makes this connection between herself and the caterpillar explicit in “If I Were,” the thirtieth and closing poem of the prose poem series. The title leads into the poem so that it reads

“If I Were…A caterpillar of any kind, somehow blessed (or cursed) with a mind, I would leafmeal pray that I be spared from the fate of dying with unspun thread still inside my body. In the end, silkworms die soon enough whether or not they have completed their cocoon project…The rate of their own shroud-making is one foot per minute.”

Here, in the elegiac figure of the silkworm spinning its own shroud, Nonaka suggests answers to the implicit question, what is the cost of beauty?—time, the body, the self, all of which are more eloquently, more poignantly, articulated in the dynamic, singular image of the shrouded silkworm than in any abstract verbal iteration. In The Museum of Small Bones, Nonaka shows herself to be a poet of thoughtful, measured vision, with an expert ability to render the philosophical in the concrete. I eagerly look forward to more work from her.

Miho Nonaka is a bilingual poet from Tokyo. Her first book of poems, The Museum of Small Bones, is scheduled to appear from the Ashland Poetry Press in 2019. Her poems and essays have appeared in various journals and anthologies, including Iowa Review, Kenyon Review, Missouri Review, Ploughshares, Prairie Schooner, Southern Review, Tin House, American Odysseys: Writings by New Americans and Helen Burns Poetry Anthology: New Voices from the Academy of American Poets. She is an associate professor of English and creative writing at Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois.