review of Radium Girl by Celeste Lipkes.

University of Wisconsin Press, 2023.

Diane Seuss, in her essay “Restless Herd,” addresses poets. She says, “In writing and ordering your poems, you are forging a self. Housing it in a stall of its own making. You are building a bearable myth.”* As I read (and reread) Celeste Lipkes’s debut, Radium Girl, I kept thinking about that phrase: “building a bearable myth.” Partly, I’m sure, it came to mind because this book conjures so many mythic feats—disappearances into thin air and metamorphoses, the dismantling of cadavers and the birthing of babies, the operation of a frictionless pulley and the reeling in of electric kitestrings—all as the means to reckon with things hard to bear: dire illness, casual sexism, God’s silence, “words that cannot stay unsaid.”

But, in studying Radium Girl, I also thought of Seuss’s definition of what it means to craft a book of poetry because she emphasizes building, and Lipkes’ “bearable myth” is an amazing piece of architecture. Structurally sound and intricately ordered, this book houses echoes by design. By design, it sets up malleable symmetries.

At least one of these symmetries the poet imports from her own story, her own transformation from patient to doctor. And the writer makes her claim on Radium Girl’s mythology clear, snapping a hospital bracelet reading “CELESTE LIPKES” around her speaker’s thin wrist, but also entering the world of medicine from the opposite door, the one reserved for practitioners. Other symmetries function by way of analogy, linking medicine and magic. Granted, the book abounds in quieter parallels, as well—among them the one that links Eve, miscarrying, to Lipkes’ first patient who, “despondent not to be dead,” has cut a “gash in her groin.” These mirrored structures and the echoes that play across Lipkes’ book, however, are not solely a matter of metaphor and motif; they are a function of the book’s design.

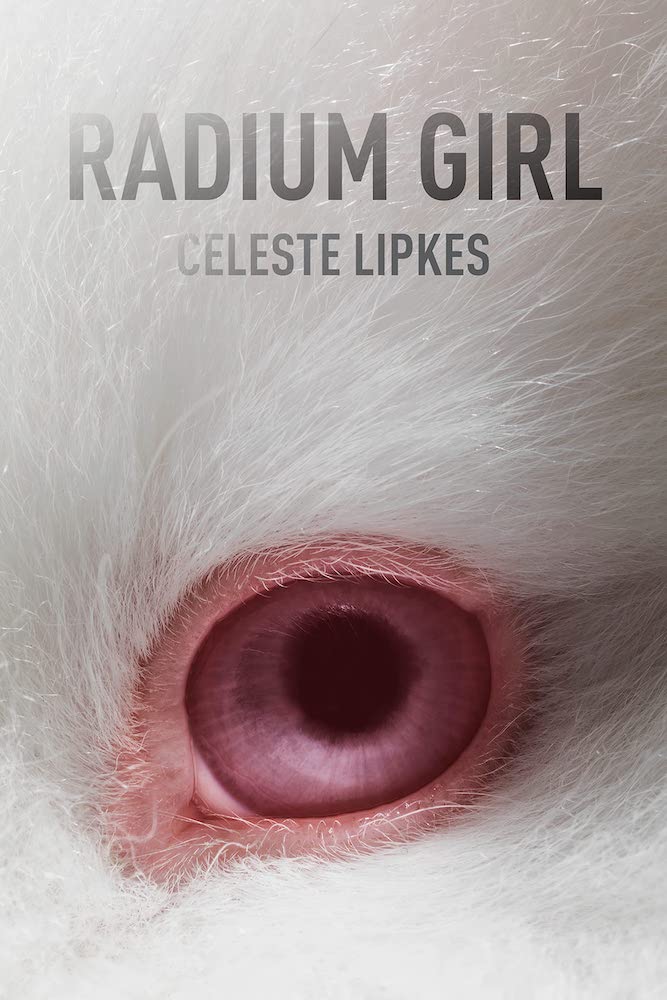

As for Radium Girl’s overt design, then, its poems are ordered within four sections, each alluding to a well-known magic trick by way of a single word: Rabbit, Dove, Hemicorporectomy, Escape. In each of the four, moreover, Lipkes sandwiches poems with individual, distinct titles between poems that share a title with the section as a whole (but are otherwise different from one another). For example, the book’s first section interlaces “sonnet,” “melᐧlifᐧerᐧous,” “Moon Face,” “Anatomy Lab,” and “Eve Miscarries” with five discrete poems named “Rabbit.”

Across the four-part structure, other deliberate patterns emerge. Each section includes one poem that, like “melᐧlifᐧerᐧous,” has, for a title, a rare word divided into its syllables—followed by an epigraph announcing the word’s definition. And each section includes a poem that, partway through, turns ekphrastic, citing the name of a painting and artist. Twice the painting’s subject is St. Anthony’s temptation, and always the artwork features something fearsome in the sky; when it’s not Dali’s “caravan of demons/ with spindly stilt legs” or Cezanne’s monstrous seductress, it’s a couple levitating in Chagall’s Over the Town or Redon’s weird dirigible in The Eye, Like a Strange Balloon, Moves Toward Infinity. The first three parts of Radium Girl also contain a villanelle apiece.

The absence, however, of a villanelle in part four, “Escape,” is not a fluke. Rather, the magic of escape, of shedding restraints, seeps into the poetry, and Lipkes forgoes the constraints of form, too. Indeed, the occasional artful departure from pattern is one facet of this poet’s brilliance.

Which is not to imply that she inhabits pattern any less brilliantly. On the contrary: one of my favorite poems in Radium Girl is the villanelle “Hospital through a Teleidoscope,” quoted here in its entirety:

In bed, I shake the world by turning glass.

Twisting the plastic tube, I shut one eye,

watch the people break apart and pass

out of my lens. This is my morning mass—

mosaic of pills, white nurses floating by.

In bed, I shake the world. By turning glass,

I split the mother’s dying son, the brass-

necked stethoscope, the doctor’s tucked-in tie.

I watch the people break apart and pass

my curtained room. I fill six test tubes, wineglass-

thin, with blood. I fast. I sleep. I lie

in bed. I shake. The world, by turning glass

to dust, scatters what we thought would last.

The mother down the hall keeps screaming, Why?

I watch the people break apart and pass

away. That night, the doctor cups my mass,

benign, like bread between his hands. I cry

in bed. I shake the world. By turning glass,

I watch the people break apart and pass.

Like the teleidoscope, which fractures and tessellates the objects which one views through it, the villanelle practices fracture and repetition, embodying the way that time passes in the hospital, the way illness shatters and loops experience. But this poem also demonstrates, in microcosm, the slyness with which Lipkes overlays seemingly incompatible ways of making sense of suffering, mapping religious sacrament onto the rites of medicine, then merging an ordinary patient and his desperate mother with the traditional pietà, Mary cradling the crucified Christ. Importantly, this holding of multiple truths, those of faith and science, for instance—along with their intrinsic uncertainties—is another way in which the architecture of Radium Girl “build[s] a bearable myth.” Perhaps the myth is more bearable because it contains room for altars and anatomy labs and trapdoors, for rabbit hutches and IV poles.

And because it has room to move this furniture around. Lipkes, in fact, points out how alterable her poetry’s arrangements are. Early in the volume, she writes:

In the schema I have established

the doctor is the magician

and I am the rabbit.

But I regret to inform you

that there are other possibilities.

She then outlines those “other possibilities.” One is the magician God “pulling the disease / from the hat of [her] body,” another the magician poet “finding inside the darkness / a small trembling thing” and protesting “This is someone else’s rabbit.” The lines that open this specific poem named “Rabbit,” though, also have their symmetrical double in the poem third from the collection’s end. That they do of course demonstrates again Lipkes’s understanding that, though she can impose a structure, a “schema,” on the world that she navigates, mutability persists.

In the schema I have established

the patient is the magician

and the illness is the handcuffs.

But again: there are other possibilities.

The same poem closes with a broader acknowledgment, one that crosses the blank space on the page to implicate the reader, as well:

Even poems are a trap

to break free from.

In this way you are also a magician.

If you find a way out,

please let me know.

While this collection is an astoundingly constructed myth, then, it does not resolve the wonders it summons. This particular poem, for instance, does not close; it waits on an answer. As for the book as a whole, it does not end in certainty, trimming the “other possibilities” from its schemas. Rather, it bears the traces of its construction; it tenders the reader a coupon good for its deconstruction or, maybe, reconstruction. It shimmers between mythography and mythology, between being made and being un- and re-made. Put another way: Radium Girl is no fait accompli but, instead, a gorgeous, assailable performance, splendid and incomplete. It is the “building,” before our eyes, of “a bearable myth.”

* Seuss’s “Restless Herd” appears in Marbles on the Floor: Assembling a Book of Poems, edited by Sarah Giragosian and Virginia Conchan.