AKHIL KATYAL ♦ ANAND THAKORE ♦ ANINDITA SENGUPTA ♦ ARUNDHATHI SUBRAMANIAM ♦ VINOD KUMAR SHUKLA TRANSLATED BY ARVIND KRISHNA MEHROTRA ♦ CP SURENDRAN ♦ DEVASHISH MAKHIJA ♦ ELLEN KOMBIYIL ♦ HOSHANG MERCHANT ♦ KEKI DARUWALLA ♦ MENKA SHIVDASANI ♦ MICHAEL CREIGHTON ♦ MINAL HAJRATWALA ♦ NITOO DAS ♦ RANJANI MURALI ♦ RANJIT HOSKOTE♦ RAVI SHANKAR ♦ SAMPURNA CHATTARJI ♦ SHIKHA MALAVIYA ♦ SUNU CHANDY ♦ VANDANA KHANNA

© Photo, Courtesy Santosh Verma

“I cannot be in two places at once:

That is axiomatic.”

From Madras Central by Vijay Nambisan

I am in two places when I write this. It is a Tuesday in late October in a city in America. Outside my window is the morning forest still green although autumn has arrived. The air is crisp, a cool balm. Insects buzz and leaf blowers scream over the hum of traffic. I feel like I am being watched and search the undergrowth. A stag is staring at me, gold antlers against tree bark. It is as still as a yogi.

In Bombay, nine and a half hours ahead of me, it is Tuesday evening. I imagine myself yet again a part of Loquations, a group started by essayist and poet Adil Jussawalla. A dozen of us, including Anand Thakore featured here, would gather outdoors in the tropical gardens of the National Center for the Performing Arts, sharing poets we loved. We were close to the ocean, the monsoon had left the island by mid-October, and the sea had calmed, no more fish thrown up by thrashing waves onto asphalt. The heat eased by the evening in the shade of the stone buildings. We read many poets spanning centuries, continents and languages – Jorge Luis Borges, Italo Calvino, Ted Hughes, and Christina Rossetti. When you are at the crossroads, in a port town gifted to the British as dowry for a Portuguese princess, your very nature is to include, bring in, and listen to the world. In ‘Father of Mr S’ Vivek Narayanan writes, “Ah but I speak/ your English, wear your pants; why/ o why must I feel useless/ amidst your life’s unlikely reach?”

And so here I am, at once in two places, excited to bring you new poems from twenty-one poets writing in English, who trace at least some of their experience or heritage to India.

In his 1976 poem ‘Missing Person’, Jussawalla wrote:

“‘You’re our country’s lost property

with no office to claim you back.

You’re polluting our sounds. You’re so rude.

‘Get back to your language,’ they say.”

That was then. Now, and perhaps after The Bloodaxe Book of Contemporary Indian Poets (2008) edited by Jeet Thayil, some of the issues have been thrashed out and many of us don’t feel the need to justify the voice of the Indian poet writing in English. Thayil writes, “Indian poetry, wherever its writers are based, should really be seen as one body of work.” So over here we are not going to have debates about traitors or heroes. As Indian poets writing in English, we know we are a minority, and our readership is small, even as it is growing. For the Indian poet in America, the problem is explored by Sunu Chandy in ‘Shelter-In-Place (2017)’ and by Minal Hajratwala in ‘Decomposition’.

On my desk I have sketched a rough map of the world and over India I’ve written “Enter Here, All are Welcome”. It’s a tongue-in-cheek way of accepting both conqueror and influence, and stating that for the contemporary Indian poet, born in India or not, living there or elsewhere, there is no desire to be part of an exclusive club. This openness is a fact of our transnational lives. At the same time, we are inward looking – for so much great Indian literature is in numerous Indian languages and many of us are multi-lingual. We have some fluency in Hindi, we understand the language of our family (in my case Gujarati) and can somewhat comprehend the language of our state (in my case Marathi). And it has been the life’s work of poets like Arvind Krishna Mehrotra to translate Hindi and Prakrit poetry into English. In this anthology we see two poems by Vinod Kumar Shukla, a Hindi poet, translated by Mehrotra.

T.S. Eliot said to Ted Hughes, “There’s only one way a poet can develop his actual writing — apart from self-criticism & continual practice. And that is by reading other poetry aloud — and it doesn’t matter whether he understands it or not (i.e. even if it is in another language.) What matters, above all, is educating the ear.” Poetry groups like Loquations are elective spaces, inclusive, open to all, including writers in other Indian vernaculars, and the non-Indian poet. Jussawalla, one of the finest modern poets in the English language was seeking to make us better readers. One such informal group was begun by Vivek Narayanan when he lived in New Delhi. From him I learned of Michael Creighton. At AWP, and Split this Rock, I met Ravi Shankar, and the founders of the [Great] Indian Poetry Collective.

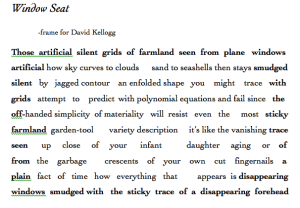

When Marc Vincenz and Danny Lawless invited me to edit this featured selection on contemporary Indian poets, I asked myself how I should present the work. The connection between us is perhaps our in- between status. We are, whether in India or outside, of Indian heritage or not, of a particular sensibility, that of interlocutors. I see many of us, whatever our sexual orientation or gender identity, as the girl with the blue wings in the photograph by Santosh Verma, looking out to sea. More than our bodies, we are many voices, many forms, but always anchoring ourselves in context and history. We are sometimes greeted with surprise. The world wants to understand who we are.

This photograph captures what I want to say in this introduction. As polymorphic interlocutors, we have to be polyglots listening to myriad tongues within our shores and outside, always curious about the world. We know who we are and as we travel we set down roots again and again, as rooted nomads. And there are poets who celebrate us, like Philip Nikolayev of Fulcrum, who we easily consider our tribe, as they too are transnational, multilingual, inviting us in.

There is no exit then, nowhere not to go, we are always within, no matter where we are. “Exit there.” Where? I am not used to following signs. I do not like labels. The polymorph is a secure creature, has a voice, is brave, is confident, it throws out a challenge, like in Sunu Chandy’s ‘Shelter-in-Place’ where someone asks the narrator “No really though, where are you from again?”

“I should go home now, but I forget where that is” seems one answer, and so begins Ranjit Hoskote’s ‘Sidi Mubarak Bombay’, which is one of the poems that captures this remarkable journey of human interconnection.

In a phone conversation recently Vivek Narayanan said, “We are an open-ended community. Anyone who wants to be a part of it can invite themselves in.” Plume’s Danny Lawless and Donna Lawless have embraced this community of the imagination, making for a space that brings you this poetry. My huge thanks go to them for their many hours of support and counsel. Thank you to the wonderful poets in this folio. And thank you to Santosh Verma, for his beautiful photograph – so generously shared with Plume.

I end this Tuesday, with the voice of one more of my tribe, as I remember him sipping a glass of white wine and looking east at the Bay past the Gateway of India – the late Dom Moraes, from ‘Gone Away’ – “Yet each day turns to wander west: / And every journey ends in love.” We at Plume give you a slice of this “elective community,” with more to come.

– LEEYA MEHTA, October 24, 2017

AKHIL KATYAL

To the soldier in Siachen

Come back

the snow is treacherous,

come back

they are making you fight a treacherous war,

you were not born in snow

you do not know snow, come back,

I do not want you to fight that war in our name,

I want you to rest, I want you to be able to feel your fingers,

I want the snow in your veins to give way

for you to be able to breathe, to melt

into a corner, to sleep.

Come back.

Go home.

Go home to Dharwad,

Go home to Madurai, go home

to Vellore, Satara, Mysore,

do not stay in the snow,

go home to Ranchi, that war

is not for you to fight, that war

is not for us to give to you to fight,

let not our name be ice,

let it not heave on your shoulders,

do not let us steal your breath,

the people there, the people of the snow

do not need us, they do not need you to fight,

come back

you were not born to snow,

you do not know the treachery of snow,

go home,

to rest, go home to the sun, to water,

go home to the nights of your village,

go home to the sweltering marketplace,

to the noise of family-homes, to the sweat of the Ghats,

to the dust of the plains, go home,

may you never

have to see white like that ever again,

may you never have to see a colour

become death in your very palm.

AKHIL KATYAL is a poet currently living in New Delhi. In 2016, he was the University of Iowa International Writing Fellow. His second book of poems How Many Countries Does the Indus Cross won the Editor’s Choice Award from The Great Indian Poetry Collective and will come out from their press later this year. His first book of poems Night Charge Extra was shortlisted for the Muse India Satish Verma National Award 2015.

ANAND THAKORE

Waterhole

Something in the blood wants to leap,

Here, outside the ICU my father’s in,

His speech now taken from him,

By bandages, tubes and pipes.

What wants to leap is like the sound and stroke

Of a bright steel plectrum against a taut tuned string,

The hollow russet gourd with its bridge of horn

Leaf-decked and lacquered in Calcutta in his early teens,

Reverberating with the tiles of a mosaic floor

Laid down at his grandfather’s behest to allure the dead –

An untameable sound, febrile, metallic,

That reaches out not for perfection of pitch or form,

But for the undergrowth of forests visited in solitude,

Between sessions at court or five star hotels.

It is a music that summons the jungle home,

Beseeching it to inhabit the domain of time-hallowed metres,

And arched, ancestral walls, once believed indomitable;

Each creepered phrase, each verdurous pause,

Urging it to confer, on territories of tone

That have stood like temples,

Its uncontrollable strength.

What longs to leap is impassioned

As the sound of strings he tuned and strummed,

Pulled, plucked and put aside for years;

But also, it is as tuneless, aloof and swift,

As the single click of a black-and-white camera,

Heard, against the torrid crunch

Of desiccated leaf-beds crumpled by hooves,

Amidst crane-squawk, deer-bark, cricket-hum and baboon-hoot,

In the parched interior of a landlocked forest

Towards the end of March,

When trees turn skeletal and all streams for miles around

Run dry, all pools but this one –

His breath slowing down,

As he turns from the lens to the thought of thirst,

And rows of antlers sail cautiously into view,

Till it is time to gather with those who have gathered,

Receiving what deer and buffalo receive,

Asking to live, here only for water.

Born in Mumbai in 1971, ANAND THAKORE grew up in India and in the United Kingdom. He has spent most of his life in Mumbai. Waking In December(2001), Elephant Bathing (2011), Mughal Sequence (2011) Selected Poems (2017) and Seven Deaths And Four Scrolls are his five collections of verse. A Hindustani classical vocalist by training, he has devoted much of his life to the study, performance, composition and teaching of Hindustani vocal music. He is the founder of Harbour Line, a publishing collective, and of Kshitij, an interactive forum for musicians.

ANINDITA SENGUPTA

Agave

Flower once and die.

There’s logic in this.

Once my car stalled

outside neon nudes

on Sunset strip.

If you dawdle with strangers

thinking they’re friends,

you may be suffering

from misled courage.

The Hustler costume

does not always fit

though they say

the Sexy Hustler Baseball Girl Costume

is a surefire win

for Halloween or role-play.

Sometimes the tiniest kindness

makes you cry.

It takes a century

for the agave to bloom

a single flower.

Flash parking lights.

Wear flat shoes

so you can meet the road.

Consider desire as desert heat,

as albumen.

ANINDITA SENGUPTA is the author of City of Water (2010) and Walk Like Monsters (2016). Her work has been featured in High Desert Journal, One, Eclectica, Asian Cha and others. Her website is www.aninditasengupta.com.

ARUNDHATHI SUBRAMANIAM

Finding Dad

When fathers die

you hunt for clues

in strips

of Sorbitrate,

immaculate handwriting,

unopened cologne,

and in evening air,

traces of baritone.

You believe

they could lead

to a story larger

than the one you knew,

larger

than the face that looked up

abstractedly

from a book,

sovereign,

mysterious,

while a cricket commentary crackled inanely

on a television screen,

until you discover

the old fallacy —

the dots

never quite joined,

the clues,

never quite worked,

that even when he was around

Dad was always

piecemeal

himself just a clue,

and the only way

to his centre

is the secret way

past the epidermis

of life and books,

the carnival path

of forgetfulness.

Always has been.

And so, when fathers

disperse —

rage, laughter,

wild perplexity and all —

into ocean and fire

and sputtering sky,

into ferris-wheeling limb

and splintering desire

there’s no following

except through dance,

the great charring dance

in which they stand revealed,

divested, fallible,

whole,

whole

in the body’s gentle democracy,

whole

in the heart’s stubborn partisanship

you knew as love.

ARUNDHATHI SUBRAMANIAM is an award-winning poet whose most recent books include When God is a Traveller (winner of the inaugural Khushwant Singh Poetry Prize, and shortlisted for the TS Eliot Prize) and the Penguin anthology of sacred verse, Eating God: A Book of Bhakti Poetry. She divides her time between Mumbai and Chennai.

VINOD KUMAR SHUKLA

translated from the Hindi by ARVIND KRISHNA MEHROTRA

Two Poems

Continuously

Continuously,

at regular intervals,

one dry leaf after another

falls from the tree.

Which is why

I mutter under my breath

that the tree’s a watch, a wristwatch.

A friend overhears me.

It takes time to tell the time.

A dry leaf falls

as though it were a second.

Asked the time, I shoot back,

“Don’t know how to read it.”

A huge mahogany is ticking before you,

but to look at a watch you still must bend the neck.

The man who asked the time

looks like he’s the big cheese:

“Hello, it’s struck a new green leaf!”

“Does it matter if it’s struck two?” the friend replies curtly.

“Anyone for Moti Park?” the rickshaw-puller asks.

The friend’s nowhere to be seen.

1964

Leaving the earth

Leaving the earth,

mounting the air,

does the bird know

that it’s the earth it is leaving?

To fly above it,

you really have to go high.

And when they return

to settle on trees

do birds know

that it’s the earth they’ve returned to?

I don’t have wings.

There’s a small yellow butterfly

flying above the earth.

VINOD KUMAR SHUKLA (b. 1937) lives in Raipur, Chattisgarh, where he taught at the Indira Gandhi Agricultural University. His first collection of poems was a 20-page chapbook, Lagbhag Jaihind [Hail India, Almost] (1971), the ironic title marking him out as a new voice in Hindi poetry. He has since published several more books that include four novels, one of which, Deevar mein ek khidki rehti thi [A Window Lived in a Wall] (1997), won the Sahitya Akademi Award.

ARVIND KRISHNA MEHROTRA’S most recent book is Collected Poems (Giramondo). He is also the translator of The Absent Traveller: Prakrit Love Poetry (Penguin) and Songs of Kabir (Hachette), and editor of the Oxford India Anthology of Twelve Modern Indian Poets. With Sara Rai, he is currently translating the short fiction of Vinod Kumar Shukla.

CP SURENDRAN

Hadal

The waves white with what they witnessed

Below return, bowing and scraping

Along the shadows they throw

On shore; back,

Back to the silence thick as massed glass,

To first fish, time cutting teeth in the dark;

Ossified bones, hermaphrodite flesh, marine snow.

The cold is without thought. Things alive

Barely breathe. Your body sieves the sun

To the last. Here you are: in your element,

Feeding the sea out of your hand;

The memory-pumping heart is salt.

The sands rise from your pores,

There the shadows start.

CP SURENDRAN is a Senior Editor with the Times of India and former Editor-in-Chief of DNA. He is based in Delhi. His latest, and fifth, collection of poems, Available Light, is scheduled to come out from Speaking Tiger. His third novel Hadal was listed by Crossword as one of the best five works of fiction to have come out of India in 2016 and is being considered as the basis for a feature film. He has just finished writing his latest novel, Ceremony of Innocence, and is in the process of pitching it around.

DEVASHISH MAKHIJA

If I kill myself today

If I kill myself today

Tomorrow’s milk will curdle

untended at the door

Some clothes in the

washing machine will stay

unwashed forever

A hundred ants will gather in

quiet celebration around some

spilt tea in the kitchen

A desperate doorbell

will fall from favour

on deaf ears

If I kill myself today

Dust will gather where my

broom won’t be

reaching anymore

Ignored, a solitary banana

will rot, surrendering itself

to flies

A stubborn pigeon will wonder why

she’s not being chased out the window,

and gleefully invite some

others in

Helplessly, three bottles

of pills will age past their expiry date,

their contents intact

If I kill myself today

A cellphone will beep a reminder

at 9 a.m. tomorrow

and every ten minutes thereafter

till its battery dies

A gmail account will gather unread

emails from known ids for years

before spam slowly takes over

A Facebook profile picture will find

that it never needs to be updated

ever again

But

The elections will be held on schedule

The monsoons will come again this year

My ageing father will grow even older

The building down the road will be redeveloped

Homes will be furnished

Furniture will be bought, will age, and be replaced

The unmarried will get married

The unborn will be birthed

Newspapers will be printed

And read

And recycled

Tomatoes will be grown

Soup will be made

The kind I was prescribed for a healthier, longer life

You will have it out of a bowl

If you have it next week you will shed a tear

in my memory

it will fall in the soup

you will collect it in a spoonful

and swallow it as you

choke, and break down

If you have it next year

it will be too hot

so you will blow on it till it cools

and then you will swallow it spoonful

by spoonful

as you sit before the television

watching your favourite dinner-time soap

cursing the ad breaks

with the same intensity as today

If I kill myself today

the telecast timings will not change.

his parents gave devashish makhija his name

pure chance gave him his nationality

no one asked him if he wanted the religion he got

the system gave him an education

and then proceeded to make it null and void when he stepped out into the real world

the only thing he got to choose in his life are his words so he likes to choose them carefully

ELLEN KOMBIYIL

Nine lessons now images

sister home from school.If you kick a cat, it won’t consort with you nomore. If you throw

stones it thinks you’re throwing breadcrumbs & will

clatter after you like pigeons.Bobby P. grabbed her shoulder to turn her, stuck his mouth

on hers & swept his tongue around her gums.

Wet, my sister said, like gravel in a downpour.

Petrelli boys on their Huffys, doubled up on banana seats,

taunted us, rocks pinging the spokes.

I’m not playing your stupid game, I said. I was on line for

the slide when Bobby P. decided it was his turn

to kiss me. I gouged his cheek with my nails & had to

explain to Mrs. Glidden in front of the whole class.

You can’t catch someone if they don’t run, Mrs. Glidden said.

Catch me, she said, the room gone mute but for John-o

in the corner clapping chalk dust, which clad us in a fine

snow mist.

Mrs. Glidden had white hair that matched the baby grand she

kept in the class. Every day we’d sing Old McDonald Had

a Farm & take turns making the animal noises. We’d strain

for animals accidentally found on farms. What sound does

a bat make?, etc.

In our grid of wooden desks, the class was divided between those

who would squeal as if mice themselves, & those who’d

say “squeak squeak.”

After school Bobby P. poked me between my shoulders. I’ll do it again

I said & lifted my claws. I was clutching roadside daisies

I’d plucked, the ants still crawling in them.

ELLEN KOMBIYIL is the author of the full-length poetry collection Histories of the Future Perfect (2015), and a micro chapbook Avalanche Tunnel (2016). She is a co-Founder of The (Great) Indian Poetry Collective, a mentorship-model press publishing emerging poets from India and the diaspora and teaches creative writing at Hunter College.

HOSHANG MERCHANT

The Lotophagi

The lotophagi

have heads between their legs

(So Homer said)

They go day and night

looking for light

between their legs

I first found them in India

like Alexander

But they all belong to a single tribe

stretching from Bombay

to the Bay of Naples

They’re masked at Venice’s Mardi Gras

And in the loos of Bombay’s Victoria Terminus

they hide their names

In Africa, they hid in the grass

their heads in their ass

(like Ostriches)

But one look from your eyes

Makes the light in their eyes flare up

—Boy! Does it flare up Unforgettably

For even here

We’re all one

in seeking light

Even the men who like ostriches come from eggs

And go looking for light between their legs

HOSHANG MERCHANT is considered by many as India’s pre-eminent voice of gay liberation. He is a poet and teacher, who recently retired from the University of Hyderabad, after twenty-six years of teaching. Secret Writings of Hoshang Merchant (OUP 2016) is his most recent book.

KEKI N. DARUWALLA

Old Sailor

(on not watching the meteor storm in the heavens)

The days move on. You go by other signs;

you don’t look up, don’t steer by the stars,

or veer off into cults and odd obsessions:

summoning spirits or reading tarot cards.

You’re not a doubter, but prognostications

are not something you are prone to swallow;

especially if they deal with the heavens—

that non-existent dome over hollow

space. Doubt settles in with age like cholesterol

silting up the arteries (it couldn’t be veins!)

I didn’t waste the night, looking up

for astral fireworks that never came.

Disbelief was not something I grew up with.

Doubt and trust I always played by the ear.

Perhaps they could tell the minute or the hour

when our comet-dust would singe our atmosphere.

But the eye could not see

Those space salamanders, ephemera, wraiths.

There’s nothing like a coat of speckled rust

to line the keen edge of faith.

The nights move on; you go by other signs:

it is not dreams I wish to talk about.

The body speaks of its premonitions:

And you must always hear the body out—

The voice of the vertebrae, the neck’s sudden crick,

a bulge somewhere—the shabby heraldry of gout.

The knock at the slowly closing doors of the heart;

Will you hear the first tap? The chances are slim.

And when the body plays a certain note

dreams follow quiet as a silent film

On the same track.

You move to the next act—

a time comes when you don’t know if the curtain

goes up or down. The other day I found,

what I took for a smudge upon my glasses

was actually the first sign of a cataract.

KEKI N DARUWALLA writes poetry and fiction and lives in Delhi. His last novel was Ancestral Affairs.

MENKA SHIVDASANI

Implosion

When you have much to say

but choose the padlocked door

and feel the grating of rusted keys

upon your tongue, the levers

click and move though no one knows.

Silence descends like a butterfly on the wood

flutters and flirts with unrelenting grain.

These terrors have no sophistry,

no plutonium snaking up jelly thighs.

They fall like shrapnel from bombed-out walls,

they coat your tongue with char.

The flamingos have left our city;

this marshland swirls and gurgles in my throat.

The padlocked door has been forced open now

but the silence sticks like soot.

MENKA SHIVDASANI is the author of three collections of poetry, Nirvana at Ten Rupees, Stet and Safe House. She is co-translator of Freedom and Fissures, an anthology of Sindhi Partition Poetry (The Sahitya Akademi). Menka is the Mumbai coordinator of the global movement, 100 Thousand Poets for Change. She has worked as a journalist with the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong, and has co-authored/edited thirteen books, including If the Roof Leaks, Let it Leak an anthology of women’s writing. She has also edited two anthologies of contemporary Indian poetry for the American e-zine www.bigbridge.org.

MICHAEL CREIGHTON

On the Badarpur Border

We take the Violet Line as far south

as it will carry us and start walking

into the borderlands. You tell me

you are looking for a language

with which to speak of this place

and others like it, but I have little to offer:

I’m not even sure what state we are in now,

and when you ask, I can tell you neither

the name nor the source of the dark pool

that rests there between worn bricks

and hard ground; it hasn’t rained for days,

so I suspect it is fed by one of the small drains

that run through the jumble of shacks

that line this road, but we’re not close

enough to smell it, so I can’t be sure.

There are mysteries in this land

between city and sprawl

that would take much digging

to uncover: the origin of the cluster

of well-built flats we passed through

just now, or how much of the green

and brown hillside near the railway tracks

is trash and how much is soil—

whether we should name it ‘landfill’

or ‘landscape’. Of course, there are things

I’m more confident of: I’d call that oxcart,

an ‘oxcart’, and that auto, an ‘auto’,

and from their lean and smiles,

I’d call the pair of straight-backed men

that just pedaled past us, ‘friends.’

In the end, so much depends on us:

we’d agree that the rows of new and used

bicycle wheels hanging outside that shop

are ‘cycle wheels’, but while they remind me

of a cycle mechanic I once loved in Portland,

for you they will conjure something different,

and perhaps even more beautiful.

I don’t ask you about the fine dust

that floats all around us, but to me

it tastes like grief and home,

and as for the smoke that hangs

between us now, it is a ritual,

but what I don’t tell you is that for me,

it is also a prayer, like the point in the Mass

where the priest says,

Pray, my brothers and sisters,

that our sacrifice may be acceptable.

MICHAEL CREIGHTON is a middle school teacher and library movement activist in New Delhi, where he’s lived since 2005. He’s published poems in journals and newspapers including Wasafiri, Pratilipi, Mint Lounge, Softblow, The Sunday Oregonian, and City: a Quarterly Journal of South Asian Literature.

MINAL HAJRATWALA

Decomposition

“When you’re here, let’s speak American. Let’s speak English, and that’s a kind of a unifying aspect of a nation is the language that is understood by all.” —Sarah Palin

Beware: The Englishes are gathering like fleas.

They are pillaging your picnic,

swarming o’er your cheese.

Geechee to Malayalam,

İngilazca, Konglish, Scouse

they are swallowing your cupcakes

& licking at your knees.

Pakeha, do you feel them

scribble-scratching your dis-ease?

Haole gaijin goraa mzunga,

what’s that in your weeping trees?

See, these Englishes are buzzing,

pollinating your newsfeeds,

pidgins, creoles, acrolects

slurrying your deep freeze.

Your faint iambic fragments,

false positives, slant rhymes

can’t band-battle these sweet Englishes

loop-de-looping double-time. So take

a break or bake a cake & cock

your ear but dock your tongue

& listen to the Englishes

remix, resorb, rejoice:

hum.

MINAL HAJRATWALA’S books include Leaving India: My Family’s Journey from Five Villages to Five Continents (winner of four nonfiction awards), Bountiful Instructions for Enlightenment (poetry), and Out! Stories from the New Queer India (anthology). She co-founded The (Great) Indian Poetry Collective and created Write Like a Unicorn to help writers tap their magic.

NITOO DAS

Spotting a Spotted Forktail

He surfaces. A screel at first light.

He is alone and at leisure. He is

talking to himself, pecking at the waterfall,

questioning the mud, stepping

towards the centre. He sprints

like the scattered prints of a newspaper.

He is a chess game speckled

with dots. A zebra bird

with strategic fullstops.

A monochrome

forktrailing a contrast

where the Rhododendron drops. A ghost

in my viewfinder.

There he is again, this hasty

yin-yang bird, not a little wiser.

He poses a while and then

is pulled

with sobs and wheezes

into the water.

NITOO DAS is a birder, caricaturist, and poet. Her first collection of poetry, Boki, was published in 2008, and her second, Cyborg Proverbs, in 2017. She teaches literature at Indraprastha College for Women, University of Delhi.

RANJANI MURALI

Your failed cartographers: AKA Raj Kapoor Tribute

Our seamless syncopations, head nods, unpunctuated

lifescape of eyes catching across the room, those

paths leading away from your cavernous home

are all hanging upside down, as if relentless fruit bats:

differentials of ebbing life, steady silhouettes

our shadows sink into at dusk. You ask me where

life lunches—at a salad bar or brewery—and I map

paths on my phone, as if your urban gravel-mazes

are surmountable, as if I know how a raincoat kiss is

different on an umbrella route, in Mumbai. How

our natural hand-holding eases itself, how this near

lifelike simulation of magnets aligning across pole-

paths unlike their own abates. You tell me there

are only so many ways in which I can please. Appease.

Different women throng your walls; I can measure

our kinship. I exult in knowing their bodies creased, in

life, these same sheets, as they do in my imagined

path-tracings. How we navigated the same hallway out, how we

are but umbra of fruit bats, listless, tethered netherward,

differing only in that we exited restaurants and breweries while

holding your eyes, our map, to your raincoat.

RANJANI MURALI teaches literature and composition in the greater Chicago area. She is the author of Blind Screens (2017) published by Almost Island. She is the recipient of fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center and the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, and has a second book forthcoming in 2018 from the Great Indian Poetry Collective.

RANJIT HOSKOTE

Sidi Mubarak Bombay

(1820-1885)

I should go home now, but I forget where that is.

A child, I was sold for a length of cotton and hammered into a link in a chain of caravans. I was taken across the sea in a dhow. The Arab slavers had been generous with the whip. The Gujarati trader who bought me had a sense of humour. He called me ‘Mubarak’, meaning ‘The Blessed One’. Many years I worked for him in Bombay. City of opium warehouses. City of cotton godowns. City of spice stores. City of jahazis, munshis, khalasis, sarafs, bhishtis, sepoys that was the only family I knew. So I called myself Bombay. My master died, leaving instructions that I was to be freed. I went back to Zanzibar and built a house. In Bombay I was a Sidi, a man from the Zanj, a man the colour of night. In Zanzibar, I spoke Hindustani and English, stuttered in Kiswahili. But this old, this new country spoke to me in rhymes of soil, sand, river, and jungle. It brought me gold. Coral. And pearls.

Speke Sahib, Bwana Speke, wanted me to be his guide. Then Burton Sahib came. Bwana Burton. Then Bwana Stanley. Bwana Speke was looking for the source of the Nile. So were they all. I was their compass and their sextant. With them, I looked for the source of the Nile. Once, we nearly died. As if the journey was cursed. Burton Sahib vomiting all the time. Bwana Speke slowly going blind, his eyes gummy and swollen with too much dreaming. At last, Ujiji. The lake rippled from one end of the world to the other. It was as wide as a sea cradled in a giant’s palm. God forgive us, we tried to cross it. Bwana Speke lost his hearing. A beetle had crawled into his ear. What afrit possessed him I don’t know, but he tried to get it out with a knife. No boats large enough to cross that lake. Later, I crossed Africa from coast to coast. Walked more than any other man alive. Logged six thousand miles, most of it on foot, match that if you can. Sometimes donkeys.

Long after I left Bombay and went back to Zanzibar, its smells followed me: freshly chopped garlic, fenugreek, asafoetida, pepper, cinnamon, bombil drying in a sharp wind. “Bombil,” I would say to myself, sitting on my stoop, looking across the sea, rolling the syllables in my mouth. “Bombil, surmai, bangda, rawas.” The soft, masala-thick pungency of one fish after another after another would settle on my tongue. My neighbours must have thought I was chanting spells.

RANJIT HOSKOTE is a poet, cultural theorist and curator. He is the author of 30 books, including Vanishing Acts: New & Selected Poems 1985-2005 (Penguin, 2006), Central Time (Viking, 2014), and an award-winning translation of the 14th-century Kashmiri mystic Lal Ded, I, Lalla: The Poems of Lal Ded (Penguin Classics, 2011). His next book of poems, Jonahwhale, is due out from Penguin in 2018.

RAVI SHANKAR

RAVI SHANKAR is the author, editor or translator of over a dozen books and chapbooks, including most recently The Golden Shovel: New Poems Honoring Gwendolyn Brooks (University of Arkansas Press, 2017) and Andal: The Autobiography of A Goddess (Zubaan Books/University of Chicago Press, 2016). He teaches and performs around the world, most recently for the New York Writers Workshop and as the Writer-in-Residence at Sun Yat-Sen University in Guangzhou, China. He currently holds a research fellowship from the University of Sydney and his memoir-in-progress is entitled Correctional.

SAMPURNA CHATTARJI

Bookish—two poems

the silence that

jumps out to haunt her from page one

hundred and forty nine

– Áine Ní Ghlinn

the mysterious disappearance of the cheese *

there was a cheese not 30 kilos of Gruyère

Kalimpong

waxy wheel of heaven

smelling high

slices salt

beyond recompense

so ordinary to have it in the larder

this chthonic O un

sullied

till we ate a wedge into it

pie-chart

percentage of girl children going to school

percentage marrying early

dying early

percentage of pregnancies

pie-charts in school un

connected with the wide waxy wheel of wholesome

heaven in the larder

of replenishment

where did it go?

there was another cheese introduced later

in my life

Bandel

product

of the Portuguese

settled

in Bengal

the small O of

forefinger

and thumb

rounds of harder-than-chhurpi

meant for

chewing

on the upslopes

discs slightly dirty

on the counter

as he wraps them

a few

may roll away

play-wheels

soaked in water

to a softness

smoky with

fires I have never

stopped

stoking

[73] Threatening Weather **

there’s a tuba brewing

headless torso (female)

cut off just above the pubes

there’s a chair in the air

it’s Marseille again

first-ever-seen

straw-bottomed woven chair

(she is flesh not marble

that much is clear)

photographed in the sun

above the Old Port

never sat-in chair of con

templative mo(ve)ment

what can I say to you

three graces impending?

there will be storm before

the lull(aby)

there will be milk from

touchable nipples

there will be shore

made of implacable

time

(fallopian tubes)

*pg 149, Marguerite Duras: The War: A Memoir

** pg. 149, Alain Robbe-Grillet/ René Magritte: La Belle Captive: A Novel

SAMPURNA CHATTARJI is a poet, fiction-writer and translator. Her fourteen books include two novels, Rupture and Land of the Well (both from HarperCollins); a collection of short stories about Mumbai/Bombay, Dirty Love (Penguin 2013); and five poetry titles, the latest of which is a book-length sequence of poems, Space Gulliver: Chronicles of an Alien (HarperCollins 2015). You can find her online at https://sampurnachattarji.wordpress.com/

SHIKHA MALAVIYA

Portrait of a South Asian Silicon Valley Housewife

What if they knew that that once upon a time, a saggy homespun khadi bag hung from your shoulder like a third arm, and inside its rough-hewn open mouth, a much-thumbed copy of Neruda’s Isla Negra and Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet. You left one peninsula for the other, from palms drooping with tender coconuts to ornamental palms that flap empty handed, high-fiving California sky. And now a Louis V hangs from your wrist, not the fake kind from Shilin Night Market that a friend bought you two summers ago when they visited Taiwan, but the real one that comes with a certificate, the culmination of forty birthdays. You don’t tell them your Mercedes is leased or that your son finished the year’s math curriculum over the summer yet still wets his bed or that your solitaire earrings are a warehouse find. You don’t tell them that your hubby was laid off once and passed over for a promotion twice. At the company party, you down three margaritas as they talk digits: IPOs, the SAT, hey, what’s your A1C? And how so and so got their house for only 2.5 million, after overbidding by $300,000. And then the suicides, heart attacks and cancer. Stress and age, they all murmur as they munch on cocktail samosas. You thank God it isn’t your family or your friends and then remember that you must renew your gym membership at the Y. You go home in your little Mercedes convertible and disengage the security alarm, then let the dog out to pee. The weather is a mild 70 degrees. You peel off your little black dress, pull on your nightgown embroidered with magenta flowers that is gaudy (courtesy of his mom), but so comfortable, and somehow it smells of back home, of sewing machine oil and brown fingers. You switch on your favorite soap on Zee TV, via satellite, nursing a cup of ginger tea, ready to see what that wily daughter-in-law, dressed to the ethnic nines, will do this time to make her mother-in-law hate her on the inside but love her on the outside, and for a brief second all’s right with the world.

SHIKHA MALAVIYA (www.shikhamalaviya.com) is an Indo-American poet & writer. Her book, Geography of Tongues, was published in December 2013. Shikha is a co-founder of The (Great) Indian Poetry Collective, a literary press dedicated to new poetic voices from India & the Indian Diaspora. Her poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and featured in Prairie Schooner, Drunken Boat, Water~Stone Review & other journals. She has been a mentor for AWP’s Writer to Writer Mentorship Program & was selected as Poet Laureate of San Ramon, CA, 2016. She currently lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.

SUNU CHANDY

Shelter-In-Place (2017)

Part One: Oath of Office

I pledge allegiance to the church basement meetings

to the chairs in a circle. To the volunteer lawyers at the airport

and the ones running to file in the federal courts. I pledge

allegiance to keeping my paycheck until I have a new one.

I pledge to bravery and fear equally and that’s the problem.

I pledge allegiance to my child – to seeing her before

she goes to bed at night, at least some of the time. I pledge

allegiance to poetry, to protesting, to resisting

where and how we can. I pledge allegiance

to protecting my staff, to standing in the hallway

with management, quietly grieving. I pledge

allegiance to leadership, to loneliness, to only crying

during our commutes. I pledge allegiance to vacations

over objects, to experiences over things. I pledge

allegiance to nice things, the smallest things, to flowers

for the boss on the worst of her days, and flowers for all

of us too. I pledge allegiance to facing conflict head-on

and to choosing our battles. I pledge allegiance to the organizers,

to the comrades, to moving through the tears, to people

sitting around a table and writing our poems anyway.

Part Two: Elk Hunting

Small talk before the first meeting with new leadership

focused on their failed elk hunting trip. Unexpected knee-deep

snow kept all the elk hidden away. Hunters disappointed,

they returned to camp. Mother Universe protected her kin,

this time. We pray for the same. A year closes

with all our dread sitting right beside us. The next morning

the radio journalist mentions an increase in hate

crime and rebel resistance. I cannot make out

which country she names.

Part Three: Questions to a Place

I am wondering if the whole country is turning into 1979, small-town Ohio again. A white gazebo in the center of town, one traffic light. It’s a 12-mile journey to the nearest grocery store. Friday evenings in the summer we head to Hillsboro to Frisch’s Big Boy for ice cream sundaes once Uncle finishes his shift. The farmers asked my father to pray for rain, or for sun, depending. Lilac bushes and a tire swing in the front yard. Tomato plants and even three kinds of roses in the back. Though something still doesn’t smell right. With our American flag in the window, we try to belong to a place where there are none of us.

We left that behind us but now it is 2017. America, will you ask if you can just call me Su again? Will you tell me I speak English well again? Will you ask me where I was born again? America, will you ask me for my papers again? Will you tell me “I don’t know where you came from, but in this country we have freedom of speech” again when I tell the three male attorneys to stop harassing the young woman? America, will you call me nigger again on College Avenue? Make me pretend to be Catholic again like I did during that first year of high school? America, will you call me Hindi again and always ask me about Indian restaurants again? America, are we back in the closet again? Does my spouse no longer have a pronoun again? Is she my roommate again? America, are we going back there again? To that “You’re pretty, well, for an Indian” again? To that, “No really though, where are you from again?”

SUNU CHANDY is the daughter of immigrants from Kerala, India. In August 2017, she left her role leading a civil rights division within a federal agency to become the legal director for a women’s rights organization. Sunu obtained her MFA in Creative Writing in 2013 from Queens College – City University of New York. She is also on the board of Split This Rock. Sunu lives in DC with her partner, their seven year-old-daughter and her partner’s grand-mother.

VANDANA KHANNA

The Goddess Tires of Being Holy

Call yourself whatever you want: girl or goddess.

Truth is, no one loves you any better. There’s

not enough gold in the world to make you feel

holy, hallowed, whole. No gloss pretty enough

to save a face marked by ash. For your trouble—

a handful of thorns, a bit of marigold dust.

This is what you get for begging to be

chosen: every god in the universe eyeing

you through the clouds like a hot wound

he can’t help but press. That terrible beating

under your skin, so loud it makes your

blood hurt, that’s the part of the story

you always get wrong—the one where

they watch you burn and burn.

VANDANA KHANNA was born in New Delhi, India and is the author of two full length collections, Train to Agra and Afternoon Masala, as well as a chapbook, The Goddess Monologues. Her work has appeared in several journals, including the New England Review, The Missouri Review, and Pleiades, among others.