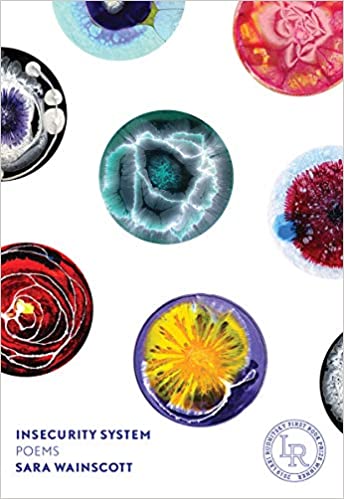

Sara Wainscott

Insecurity System

2020

Persea Books

$15.95, paperback, 78 pages.

Reviewed by Chelsea Wagenaar

Insecurity System, Sara Wainscott’s debut collection, winner of the Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize, is a series of sonnets, structured loosely as a crown. The more I considered the way she plays with the sonnet form, especially the link between one poem’s last line and the next’s opening line, I came to imagine it threaded together like a dandelion crown, the kind I used to make as a child, with one stem needled open by a thumbnail, then the slender filament of the next threaded through. I see Wainscott’s play with the sonnet crown not so much as a loosening, or a noncommittal use of it, but rather as another way of imagining how we might move—how we actually do move—from one thought to the next.

Here are a few examples of my favorite closing to opening lines. “[When girls sit in parked cars]” closes with the line, “It’s easy to pretend to be asleep,” which initiates the next poem as “Sleep is the pretense of ease.” The shade of difference between “pretend” and “pretense” is only the distance from verb to noun, but Wainscott always manages to capture the less explicable connotative differences—the way the realm of “pretend” belongs to children, but “pretense” to adults, the way that achieving the appearance of ease—rather than ease itself—is often our desire, and rarely actually easy. In the next two poems, the closing “Pairs of legs flung rowdily around” morphs to “Around the flowering pears,” so that “pairs” is homophoned into “pears” and the assonance of “rowdily” echoes in “flowering.” Wainscott is doing what Richard Hugo describes in his most famous essay, “The Triggering Town,” in which he argues that the poet’s allegiance should shift away from the meaning of the word and toward the music of the word. This openness to imaginative play, to discovery, propels the poem and blows open the possibility for surprise.

This quality of movement from one thought to the next is one of Insecurity System’s most striking features. The logic of these poems takes on a near daydream quality, at times, representing the inarticulable, flitting shift of one sensation, observation, or reaction to the next. In reality, when we think this way, in the harried, forgettable way we do, there is little of sustainable interest, but Wainscott manages to bring this daydream logic to the page and chisel it into neat precision without losing its deeply associative, intensely recognizable quality. Here’s the first half of “[A band of moonlight spreads]”:

A band of moonlight spreads

across the bedroom windowpane,

thin and clear as vinegar.

Fish live on the moon and swim

by night, bright milk-eyes

who lip the ovaries.

In my next life I will love you better.

Wainscott is rarely as candid as “In my next life I will love you better,” but because she so seldomly risks a sentiment like that—in fact, she seems suspicious of it—the poem earns the moment. The wistfulness of that line picks up the moonlight “thin and clear as vinegar,” a note of ambivalence more typical of the collection, which has stocked its poems with roses and moonlight and then unsentimentalized them, stripped them of their tired symbolism. Her tendency to pair the floral with the rugged is apparent throughout, as in the lines “The rosebush I love best / grows on the roadside boulevard,” from “[Pills and rage, I reply when people say],” a poem that typifies her adept command of everyday language—“I take pictures on my phone”—alongside the high poetic: “Upon the pikes the pink heads glower,” the latter of which still manages to turn my expectation for “flower” into the unexpectedly sinister “glower.”

Insecurity System’s daydream logic and its impressive range of diction strikes me as the very opposite of thesis-driven writing; in fact, in “[The subjectivity of success],” Wainscott writes, “A thesis statement sets a limit.” But so does a sonnet, a comforting system, you might say, of fourteen lines, that gives no illusion of freedom, only the freedom to resist, endlessly, its own boundaries. The promise of a thesis, though, is a clear thought, and a faithful, traceable movement toward that thought—no straying, no wandering anywhere else. The poems of Insecurity System glory in the “else”: they go to Mars, they time travel, they ride buses and inhabit a home in an urban, skyscrapered setting. Indeed, they treat the very line—syntax itself—as an abode:

A question’s frame

projects a version of the future

in the asking. A rocket

pressed into a penny

illustrates the atom’s vaster scale.

What chasm is wonder.

This book becomes that chasm of wonder, an asking I gladly fall into.