banana [ ] by Paul Hlava Ceballos.

University of Pittsburgh Press

November 2022

ISBN 978-0-8229-6693-7

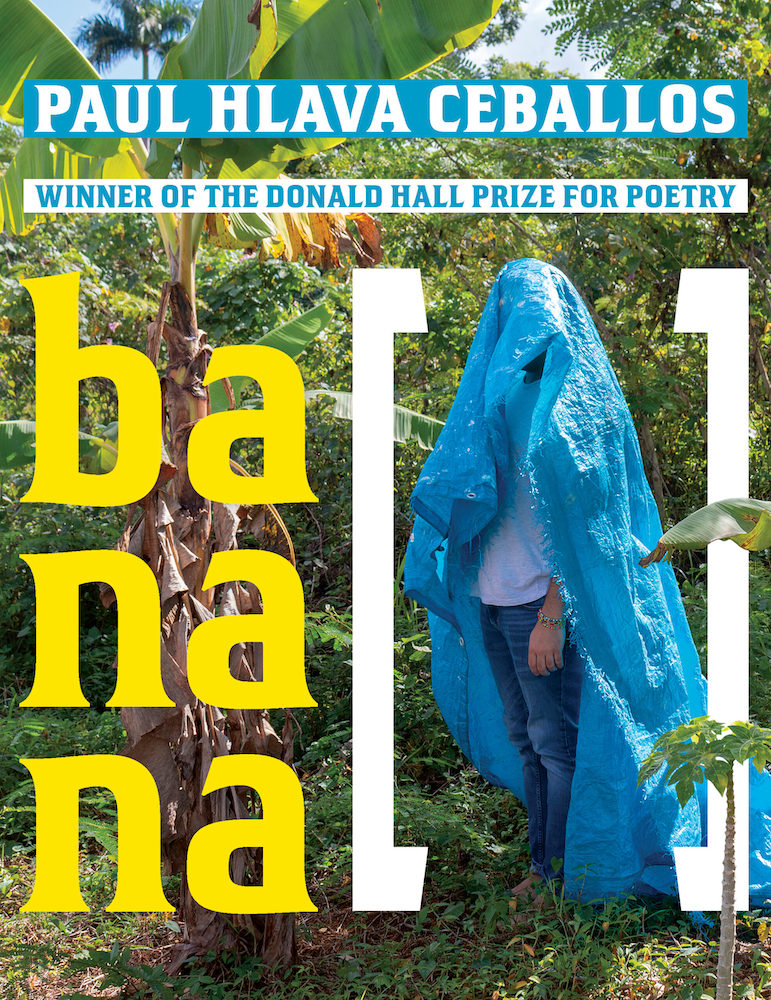

On the cover of the Paul Hlava Ceballos’s debut collection—the winner of the Donald Hall Prize for Poetry—the necessary names (the book’s, the author’s) overlay a photograph by Kevin Quiles Bonilla. To the left, the syllables of Hlava Ceballos’s title, banana, are stacked in yellow, superimposed over the trunk of a tree, genus musa. To the right, the rest of the collection’s title, [ ], stands as tall as the stacked letters and the banana tree’s trunk. Those square brackets also stand as tall as a person.

Indeed, a person is standing between them: an almost anonymous character, wearing jeans and a white T-shirt, cloaked in a blue tarp that covers their face. This figure is not quite a ghost; their body is not quite the site of an emergency. There is, in fact, a hint of playfulness about the adult who poses, mostly hidden by a waterproof blanket, in sunny foliage. But we also know that the utility of a racecar blue tarp tends to spike in crises’ aftermath. For proof, you need only think of the purposes you have seen them put to: keeping the weather out of houses that hurricanes have already tossed; lending flimsy shelter to refugees, substituting for neutral-colored winding sheets.

As a whole, banana [ ] owns that uneasy convergence of play and catastrophe. And that figure draped in the vivid blue of crises and creativity-in-a-crisis is everywhere in Hlava Ceballos’s book: in elegy and biography, quoted and mythologized, as an ancestor and a premonition. These poems’ various incarnations of that archetypal figure are, moreover, always both absent and present—always, in one way or another, missing persons. And because the characters in this text have to be conjured, pulled back onto the page or into the story from among the lost, they constantly show up as though between square brackets, like lost antecedents. banana [ ], then, is a tripartite epic of the untold.

Sometimes the book makes obvious the ways in which its characters have been left out of other narratives. In its second poem, for instance, Hlava Ceballos plays up the presence of square brackets, using them to direct attention to the shortcomings of an official press release about an immigrant shot near the border between Mexico and the United States. While some phrases of “CBP Statement on Agent Involved Shooting [Verb?] in Hidalgo, TX” are struck-through but still visible, more potent are the phrases of the prose poem that appear in italics and between square brackets. The writer, of course, has added these lines, drawing the immigrant, made anonymous and generic by protocol and politics, back into the story. Or, at least, the writer draws this man’s absence—the invisibility imposed on him—back into the story:

The incident occurred [The State employee freely shot the unarmed man] while the agent [see:

“agency”] was attempting to apprehend a subject [Language emptied of meaning is a haunting]

and the agent discharged his weapon [Oh umbrage cast wide, thrombocyte to felspar, red flowers,

red flower]. The suspect [what grammar is suspect?] [Inside a rifle’s sight a nation is sleeping]

By way of words struck out and amendments dropped in, the poem foregrounds how this would-be immigrant becomes, whether in the course of the shooting or in the course of its official telling, a canceled “subject,” “emptied of meaning” and, therefore, “a haunting.” He is, in other words, one instantiation of the anonymous person hidden in a blue tarp. In contrast, the CBP “agent [see ‘agency’]” strides through the text, unaffected, even as Hlava Ceballos replaces the matter-of-fact language of the report with an extravagant apostrophe (“Oh umbrage cast wide…”), a direct challenge (“what grammar is suspect?”), and a broad indictment (“Inside a rifle’s sight, a nation is sleeping”).

Like “CBP Statement,” the second part of banana [ ]—its long title poem—repurposes others’ words, grieving and playing at once. Hlava Ceballos describes this poem as “a collage of historical texts” in which the word “banana” appears. However, here there are no supplements in square brackets, as the poet himself notes: “The rules were that I could add line-breaks to the material and remove punctuation but could not alter the language itself.” Nowhere in Part II, then, does the writer insert outrage or eloquence. However, numbers appear everywhere, signaling 296 citations from government documents, historical tomes, interviews with plantation laborers, advertisements, documentaries, news items, think pieces, and so on.

Again, the poem does play with these preexisting texts. It pastes fragments into story and sonority. It toys with density, packing some pages with reportage and dangling only a few phrases, not justified to either margin, on others. For a series of six pages, the text becomes a column, repeating the word “banana” to the point of absurdity. An excerpt:

rats banana 157

gnaw banana 158

fabrications banana 159

like banana 160

a banana 161

President banana 162

Eventually, the word “banana” appears so regularly that semantic satiation sets in. In particular, where a noun precedes “banana,” we begin to read only the leftmost words in the poem’s narrow column, scanning it vertically. But then the article—“a”—shuttles us across the line, right to left, not down the column. Consequently, we land on the yellow fruit again, and I, for one, find myself repackaging the whole series of lines, testing the sense of “rats gnaw fabrication like a President,” against the sense of “rats gnaw fabrications like a banana.” In turn, the stanza’s entire signifying flickers. Instinctive obedience to the convention of reading across the line, heightened by the use of the indefinite article in “like a banana” feels like a glitch, an inconsistency that I can only solve by reading the lines strictly vertically (e.g., “like a President”) or row by row (e.g., “like banana a banana”). But as soon as I entertain the latter possibility, it is impossible not to see the strange honorific “President banana” and to wonder at the origin of this weird pair of words. And so on. The result, of course, is a newfound hyper-awareness of how bizarre and complicated a banana can be. First scrubbed of any signifying power by excessive repetition, by the end of these six pages where every other word is “banana,” the banana has become a hub of politics and economics and culture and agriculture.

At the same time as the meaning of the banana multiplies, though, the title poem signals its incompleteness. It points up its own lack of context, and it insists that any “History of the Americas” that has canceled certain subjects is a haunting.

What’s more, Hlava Ceballos includes photographs in Part II of his book, adding to its implicit argument that “Language emptied of meaning is a haunting.” Take the first image that accompanies this poem rife with violence and dehumanization. A person has been excised from a picture; their silhouette appears as a blank in the midst of huge stalks of bananas; their anonymous paper doll arms steady a chandelier of the crisply photographed fruits. This missing person, too, is kin to the figure in Quiles Bonilla’s photograph: a present absence, a “haunting.”

And then there is the speaker’s kin—the cousin, for instance, for whom he writes “Excarnation: Elegy.” “I tend my cousin’s Facebook page,” the poem begins, and it later asserts,

My cousin exists

nowhere and everywhere. She glows

in a friend’s hand. Her image floats

forever in air, shot mid-leap.

I follow her new followers.

Admittedly, Hlava Ceballos’s elegies mourn a different order of absence than his epic “banana [ ].” But these poems belong to the same kingdom of loss. That is, the collection’s poems of personal grief and its verses on the deaths of those less immediate to the writer share space because they are all excarnations. These poems all mark places where a subject has been excised from a story in which they belong. So, for every missing person, banana [ ] contends, there should be someone to tend their memory, to keep their “image [a]floa[t] / forever in air.” No loss should mean that someone’s cousin only “exists / nowhere.” Rather, the speaker’s cousin—we all—should “glow / in a friend’s hand.” To that end, Hlava Ceballos sings Eric Cortez—“conqueror cuffed and put away”—into specificity alongside the Incan kings. He sings the death of the trans woman who, having crossed into the United States, dies in its custody, and he sings his mother’s life, her “accent […] a spirit / summoned by a candle in the mouth.”

And where he cannot give the missing person the gift of “exist[ing] nowhere and everywhere,” he sings the square bracket, its space, its waiting on a lost antecedent: a whole story, a whole self.