Chard DeNiord on ‘The Other’

As a great admirer of Walt Whitman’s use of his transpersonal self—that “I” that is also other—throughout much of his work, I have for years attempted, often in vain, to find expression for my own transit to the other in a way that makes sublime sense; in a way that captures the personal as well as political essence of alterity in the concept of democracy. Although I prefer poetry over prose as my first mode of expression for capturing the empathic charge of divining what Gerard Manley Hopkins called “all things counter, original, spare, strange,” I have felt compelled recently in the current atavistic political climate to write an essay about the provenance and ensuing arc of that American poetry which examines the other in its essential witness to what Whitman called “the genius” of “the common people”.

Patrick Donnelly on “Callas poems”

In order to come at my own autobiography from an oblique angle, I seem to have written a sequence of poems about the great opera singer Maria Callas, 1923 – 1977. (You’ll find the whole sequence, along with other non-Callas poems, in my book Little-Known Operas, from Four Way Books in February 2019.) Callas has fascinated me for over 50 years: for my 10th birthday in 1966 I asked for a specific recording of Verdi’s Rigoletto, featuring Callas, Tito Gobbi, Giuseppe Di Stefano, and conducted by Tullio Serafin. For fans of mid-century opera, this was the “dream team,” which I must have learned about from studying the liner notes on my mother’s other opera recordings. This request frightened my father very much that I might be gay, which he was right about. (You’ll be happy to know that he and I have long since reconciled around that fact.) The funny thing is that they gave me the recording.

I don’t know why it is that our imaginations sometimes seize on one person as an object of devotion. But if you’ve ever felt this, you know what I’m talking about. The genius and virtue (vertu, as Machiavelli used the word, to mean excellence, honor, power) of that person, even far away in space and time, can be life changing or even life-saving. For a gay kid growing up in New Mexico in the 1960s, it wasn’t Callas’s personal life, which I didn’t know anything about, that was spiritually useful to me. But her strange sad voice gave me access to my own sadness. And her extreme otherness gave me a plausible model for my own otherness.

Judy Katz on “Sunday in Connecticut”

This poem is from a manuscript called How News Travels that explores the death of my mother, as well as what it means to live in a body. One of the first times I took this particular walk in winter, I was wearing boots that kept my feet warm. This, in itself, was a revelation, as I’d grown up in Memphis, TN and never quite mastered the art of dressing for New England. I remember noticing all of the color against the snow – red berries on the shrubs, a gorgeous weeping willow in the distance – and thinking, I’m actually starting to like winter. My mother had died years before, but I said these words aloud to her in a kind of ‘can you believe this?’ tone because I knew she would get a kick out of it. Since then, I’ve found this particular walk to be conducive to conversation with her — sometimes spoken, more often not. In winter, the air’s clear and crisp, and I find there’s a good connection. I am interested in how relationships evolve even after a person has died, how we still want to bring them the news.

Natasha Saje on “to the Phaistos Disc”

The poem was prompted by the news that the writing on this Cretan artifact from 1700 BC had been deciphered by Gareth Owens. It reads something like “honor and glory to the mother goddess.” (There’s a TED talk by Owens on the long process of that deciphering.) Minoan culture was matriarchal, so this is no surprise, but the specific revelation prompted my memory of a visit to the museum in Heraklion in 1977, where the disc resides. I’d probably seen it, but I didn’t know (or care about?) what I was looking at. Because patriarchy is so pervasive and ingrained in each of us, imagining a matriarchal structure is hard for us to do. There’s a big gap between a translation of symbols and understanding the concepts behind those symbols.

John A. Nieves on “The Last Few Feet”

In this poem, I really wanted to capture the way things end when everything else is going on exactly as it would be at any less important time—to highlight how finality creeps into a scene. In order to do this, I needed longer lines to keep up pace, but couplets to slow down the scene enough to allow the details to pile. I also relied on assonance tied to the long I sound. I chose this vowel so the “goodbye” would resonate across the poem. I also worked hard to make sure the sensory image built a believable space the reader could inhabit so they too would miss the leaving until it was too late.

“Yield”

This poem is an exploration of the last person left of a group of friends, the one that never really wanted anything to change, and in trying so hard to conserve a former self, became someone hard for anyone to understand. The poem plays like the tale of a Winesburgian grotesque. The music of the poem pushes and pulls to try to imitate the allure of away and the inertia of staying in place. I wanted the syntax to be both plodding and playful. I hope I struck a solid balance.

Gail Mazur on “Eastham Turnips”:

The old Cape Cod Road I’ve driven for so many years is charged with history for me, much of it naturally a story of disappearances, many of them in my lifetime. Turnips were the crop of the town of Eastham since Colonial times. Though they’d always seemed to me unappetizing, I’d begun to stop on the road on cold autumn days and buy them, never seeing the growers—I was buying history, both of farming and the trust of strangers, until it was over, reminding me of what another Cape poet called our “feast of losses.”

Sharon Dolin on ‘The Loneliness of his Death’

I was reading the recent collection of The Poems of Yehuda Amichai, edited by Robert Alter, and came upon this long poem, written in sections, called Songs of Zion the Beautiful, and was so struck by the melancholy beauty of section 29 (translated by Chana Bloch who recently died), where the chiasmus I borrowed for my title occurs in a poem recounting a man’s suicide. I have always been seduced by chiasmus and I had been thinking about all the poets who had recently taken their own lives or died prematurely, and I imagined that they were living in an afterlife with a chiastic structure, where their words and thoughts would finally be transformed. It was my way to reconnect with some beloved poet friends who had died. What else is poetry for if not to revive or at least contact the dead.

Translating José-Flore Tappy by John Taylor

I have already evoked elsewhere (in the Swiss review Viceversa) how I met José-Flore Tappy, soon translated one of her poems, then the sequence of poems in which that poem was included, then the book in which that sequence was included, and then all six of her books. This is how our bilingual edition, Sheds / Hangars: Collected Poems 1983-2013 (Bitter Oleander Press, 2014), enthusiastically took shape.

How then did we work on her seventh book, Trás-os-Montes (Éditions La Dogana, 2018), after having worked together for so long on all her previous books? As in the past, by my asking questions, many questions, such as about how exactly she sees the action “caler” with those stones that she “wedges” into the ground in one poem published here in Plume. Or, in another poem, about the personal pronoun “elle,” which suddenly struck me as perhaps referring as much to a preceding word, “l’obscurite” (darkness), as to the Portuguese woman who is at the heart of the narration. Now that I have mentioned this, let me formulate the hypothesis that the pronoun “elle” is often pivotal in Tappy’s poetry.

The poems in this book depict a village woman who lives in the remote Trás-os-Montes region of northern Portugal. She tends to her vegetable garden, performs endless chores, helps out her fellow villagers in various ways, all the while measuring “an old dream from a distance, / visiting it with her fingertips” (as Tappy puts it in another poem published here).

Another dimension emerges. A fragmentary self-portrait of the poet-narrator gradually becomes visible through, or is juxtaposed with, the portrait of the Portuguese woman. Tappy even merges with her. Moreover, the poet speaks in the first-person singular here more naturally and candidly than in her previous work, although this evolution—the initial use and then increasing personalization of the “I”—was already underway in the aforementioned Sheds. Yet this “I” can also be the Portuguese woman’s, as Tappy explores subjectivity and relationships to others from different angles, appealing in turn to the “I,” the “you,” and the aforementioned “she.” Images of gardening, sewing, or other household tasks, associated with the woman, therefore sometimes also allude discreetly to writing. Two appearances of the word “page” illustrate how the days and deeds of the two women are superposed or set side by side. The first appearance of the word occurs about a third of the way through the book in a poem published here in Plume. Both the poet and the woman are present in these opening lines: “Thin as a handkerchief / my page I scrub and clean / down to the darkness that destroys it / and is stronger than words . . .”

Two personal paths therefore run parallel, and sometimes coincide, in this book that is so remarkably illustrative of Tappy’s light touch, sharp eye, and deep-probing meditations on what is worth preserving from our haphazard being in the world. She increasingly creates a compelling sense of intimacy and outlines an existential journey that is both hers and the Portuguese woman’s. Both women are movingly imaginable in their passage through life. Has the poet’s quest, “on the other side of the mountains” (as the place name of the title literally means), attained its goal? Nearly at the end, she tenders a conclusion in which the “you” perhaps also applies to herself:

In this place without an origin,

remote from the living,

I find you again at last,

make you out

John Taylor

Sandra McPherson on ‘Archaic Rayon Kamehameha’

http://thealohashirt.net/portfolio/kamehameha-003/

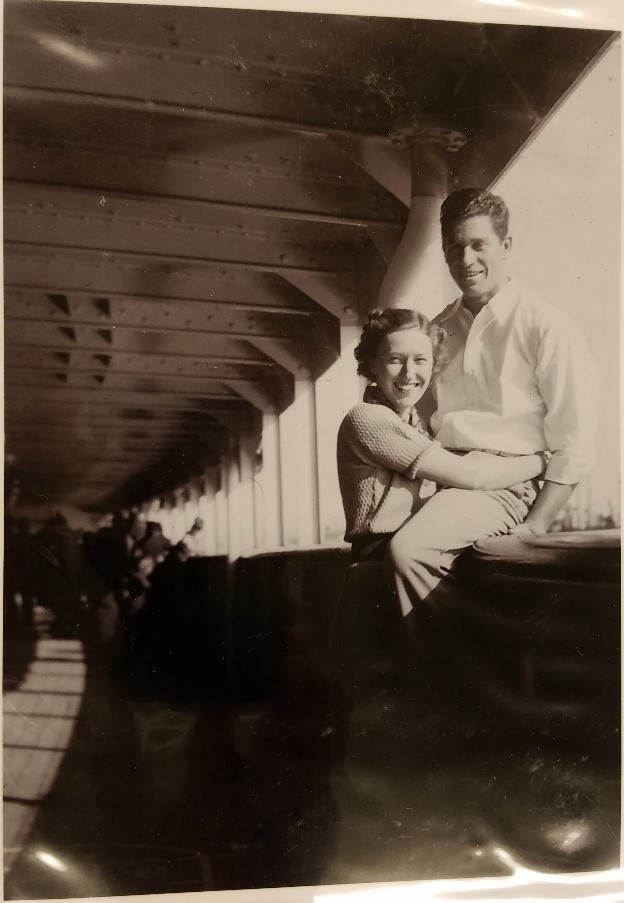

And here are Mom & Dad taking Matson Lines to Hawaii:

The poem is obviously based on the famous Rilke poem. And when I asked Dad, who survived Mom by 10 years, whether it would be smart of me to retire from teaching, he said, “Don’t hesitate!” I thought that was uncharacteristic of him, since he always thought everything out before acting. I took his advice.