THE UP DOWN OF ROMANCE

Terminations.

Graham Foust.

Flood Editions, 2023.

979-8-9857874-3-6

I once heard a literary critic say: “Fifty years from now, John Ashbery will more or less sound like Mary Oliver.” He meant our era (and poetic assumptions) will be seen in ways we can’t imagine now, in the same way poems from the 19th C have a sort of recognizable uniformity about their procedures. I’m not sure I exactly agree with aforementioned Poetic Prophet, but I get it. Fifty years from now, I’ll be dead, so it won’t really matter what I think.

*

Reading Graham Foust is an astringent, a palette cleanser. It’s like rebooting your taste. And who knows what words might come spilling out of your own mouth afterwards. After his words.

*

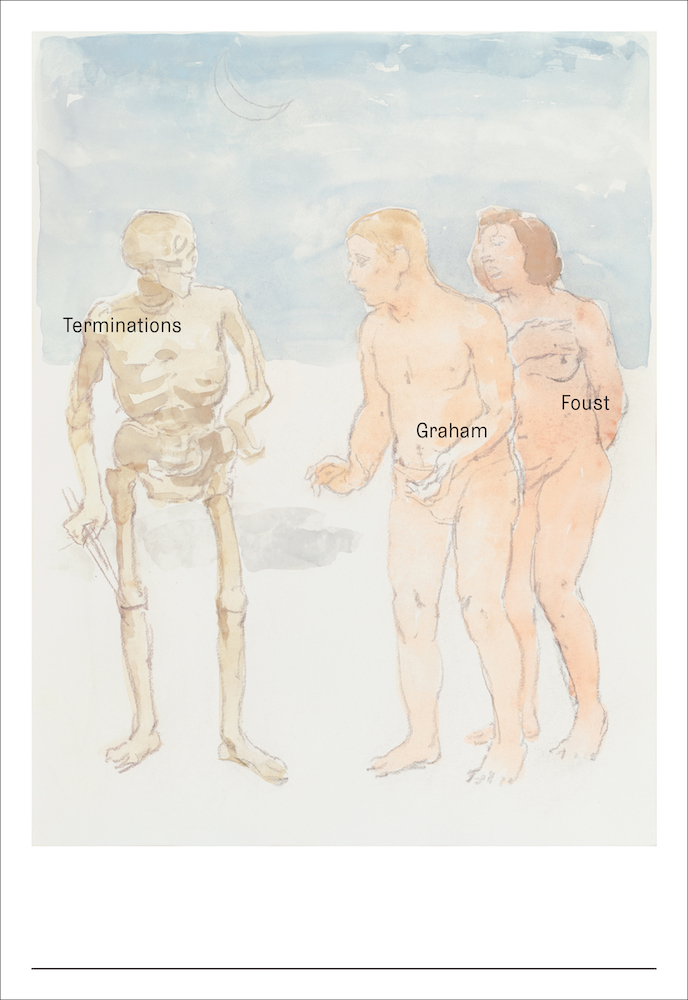

If you were to judge his latest book, Terminations, by its cover, you might learn a thing or two. Or three. The cover illustration, A Man, a Woman and a Skeleton, by Albert York, 1981, has words respectively superimposed on the images of a skeleton (Terminations), along with a naked man (Graham) and a naked woman (Foust) whose borders are touching in a garden without walls, flora or fauna, only a horizon line dividing a bluish water-colored sky from white ground with a hint of a grayish shadow or puddle. In this spare creation tableau, we are reminded of both the acts of looking and reading. Bodies. Texts. And of course naming.

*

Not to cavil, but one can see likenesses between Foust’s procedures with Ashbery’s (and even Oliver’s) when it comes to looking as both a natural and feral act, a means of lyrical survival. An Orpheus lulling beasts from wood’s edge to the confines of formal inventions. Domesticity. Love’s possibilities dancing with death and the demonic (freedom, rebellion). Rules and their breaking. Imagistes all, they start by looking (and seeing!) before arriving at something new, transgressive—readers grateful to be touched, exposed to new tastes.

*

Carl Jung said (somewhere) that what was therapeutic for his analysands were not concepts but images. Images are the medicine, poems merely the prescriptions patients sign off on, attesting to their agreement of having understood what they might be getting into. The poem as preemptive strike, as disavowal for whatever is consequential that comes after. An image seen cannot be unseen. Even if one were blinded.

*

There are moments in Foust I absolutely relish: a rat gnawing open a lover’s stitches (“Dialectical Image”); a philosophy professor urinating on a student couple passed out in a yard (“Smarts”). Confessional poems worth the price of their own admission.

*

In my mind, there is no mistaking the Tribe of Graham for the Tribe of John (or the Tribe of Mary) even if all might be charged with practicing a poetics of American Primitivism—Bill Charlie Bill’s new world naked.

*

Foust’s love lyrics read like Caveat Emptors. Meat-market purveyors à la Grindr and Hinge, you’ve been forewarned: “Two intellects / out to, yes, possess their objects.” (“Ancheoic Chamber”); “On the off chance / the other shoe // shows up down / the road, I’ll have // feelings too / famous to describe.” (“Passenger Side”). So many of Foust’s hijinks are in his enjambments, internal rhymes, the “up down” of romance and its attendant feelings defying all description, feeling states whose nuances (and developments) can be touched upon without ever being arrested or fixed.

*

Foust is a master of sleights (slights) of hand. Compare “Thoughts are where // the bottle meets / the water. // Hit send” with “Thoughts are where // the bottle meets / a flower or // its end” (“Repurposed”). Our love-worn poet leaves open which bottle he might be sending his marooned missives out in, baby or booze, such oral fixations certainly not unrelated (or untreated). Not since Creeley have I encountered shipwreck confined in a space so small. Heroic.

*

I wonder what Rilke would make of Foust’s “dream-dead” Orpheus who ruminates on “bits / of lithic in its meat” (“Orpheus”), crooning and carousing with whomever happens to come along, even if they can’t see “the memory-dredge / goes drowningly,” Foust’s penchant for puns almost always full of playful cheer: “How long has this not been going on?” (“First Mirror”). Like Cocteau’s Orphée, Foust’s dreamy divagations take us to the other side of the mirror and back again, the narcissistic wounds of Homo Ludens none worse for the wear: “No matter how seen I am by others, / I’m only seen enough to be smothered” (“Dosages”). Hard not to miss “mothered” buried in “smothered.” Devoured indeed. Deflowered.

*

Mythic. Lithic. Aphoristic. Time and again, whether “injured or jubilant” and “therefore needed to be seen,” (“Polaroid”), our pithy Mage finds himself locked inside gilt-backed poems of his own making, his brazen means circling back to their own ineluctable ends:

Immiscible

Disorder sours

when I see

you can’t see

how you look to me.