Produced by John Ebert, Editor of Video Productions

Jen Sperry Steinorth: On Creating and Claiming Space with Her Read

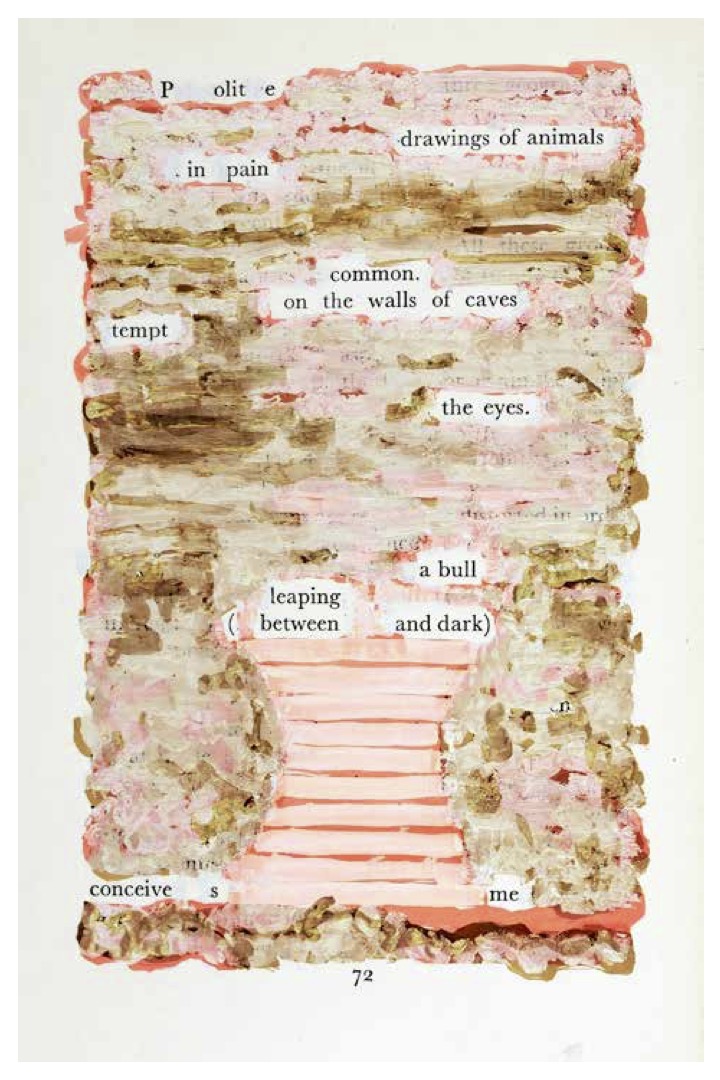

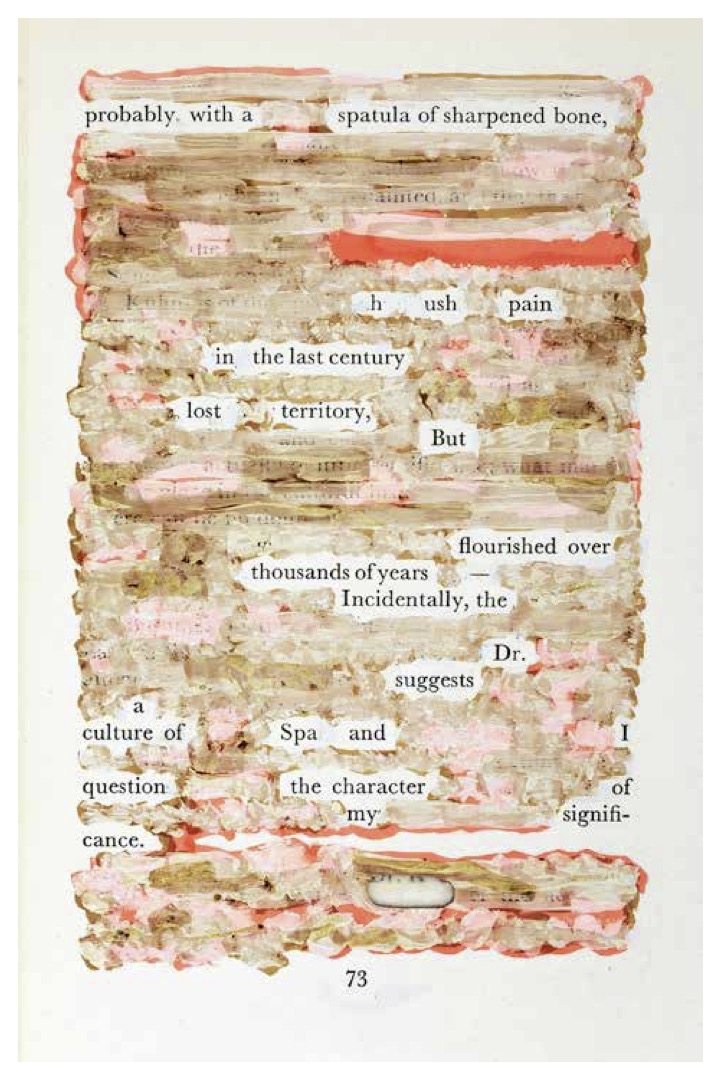

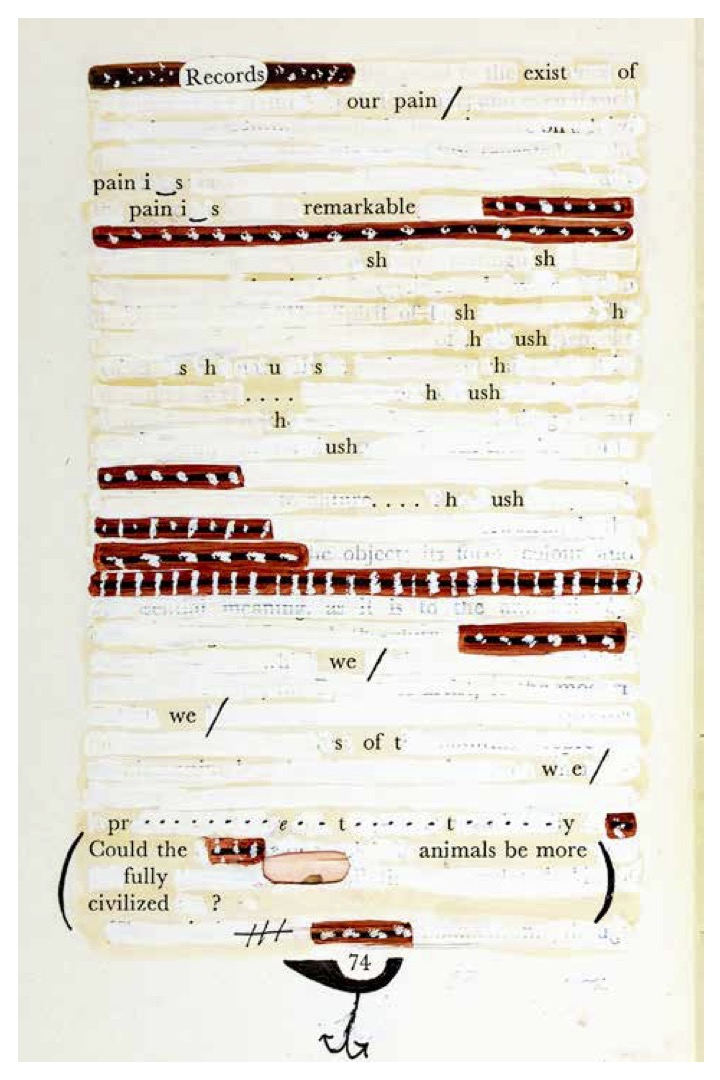

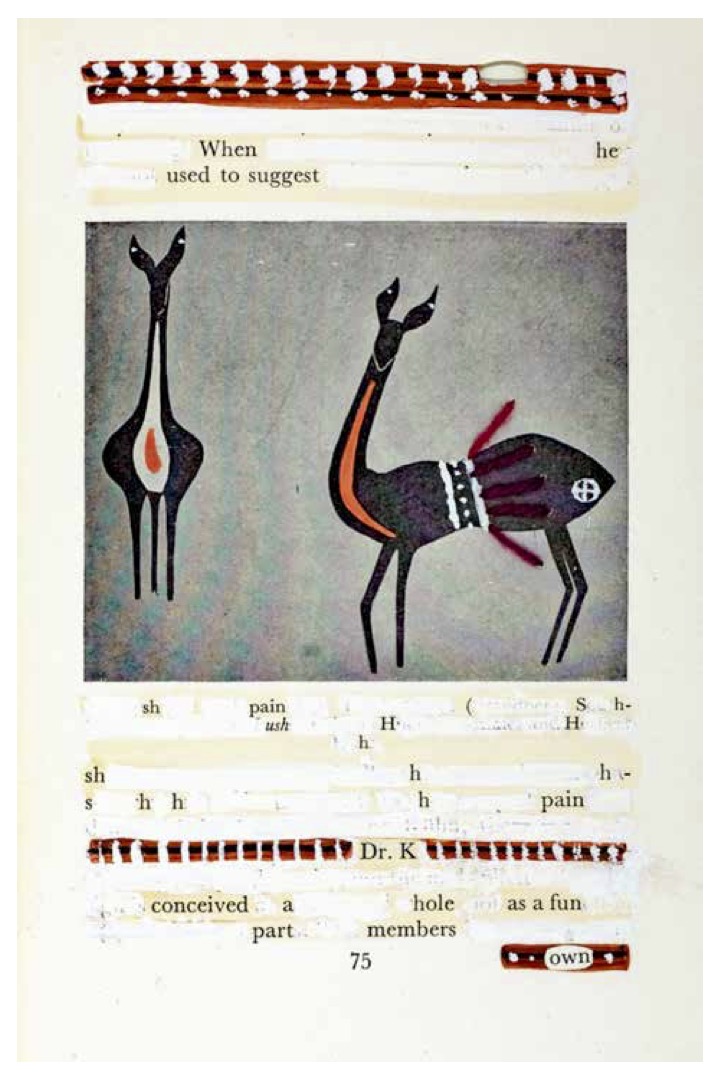

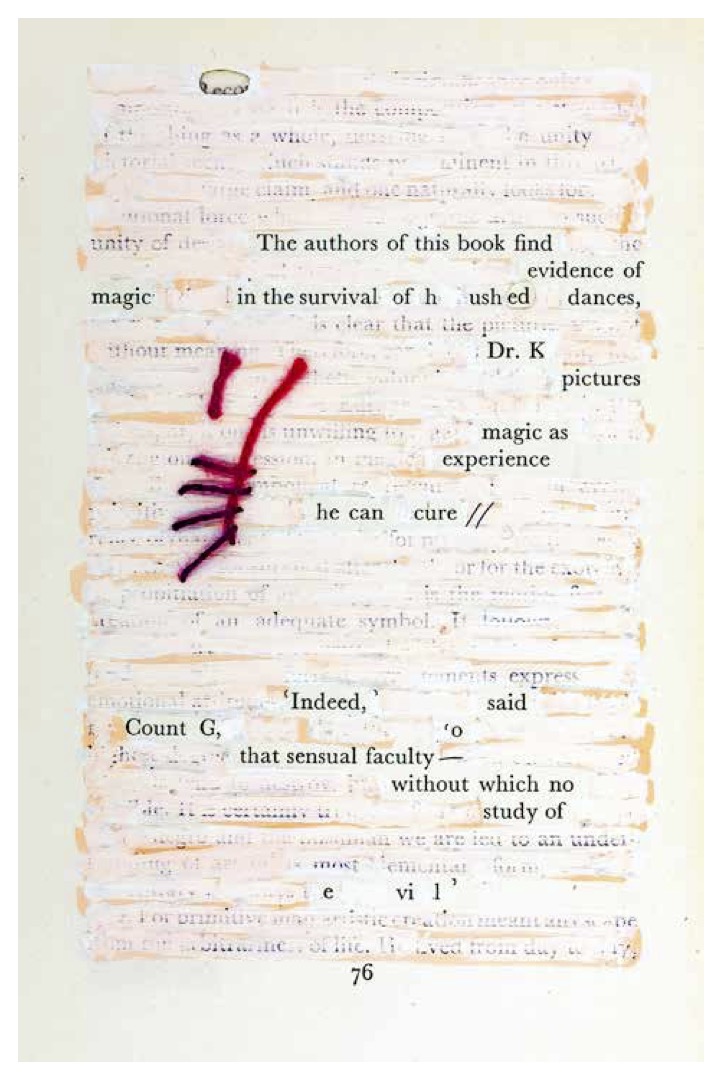

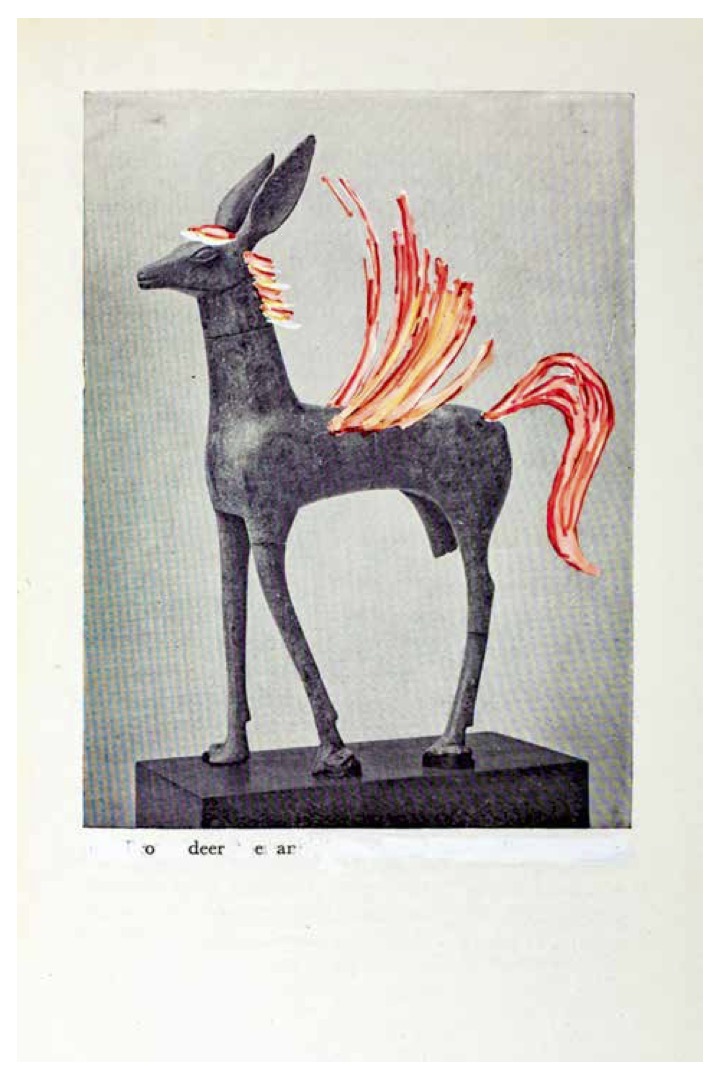

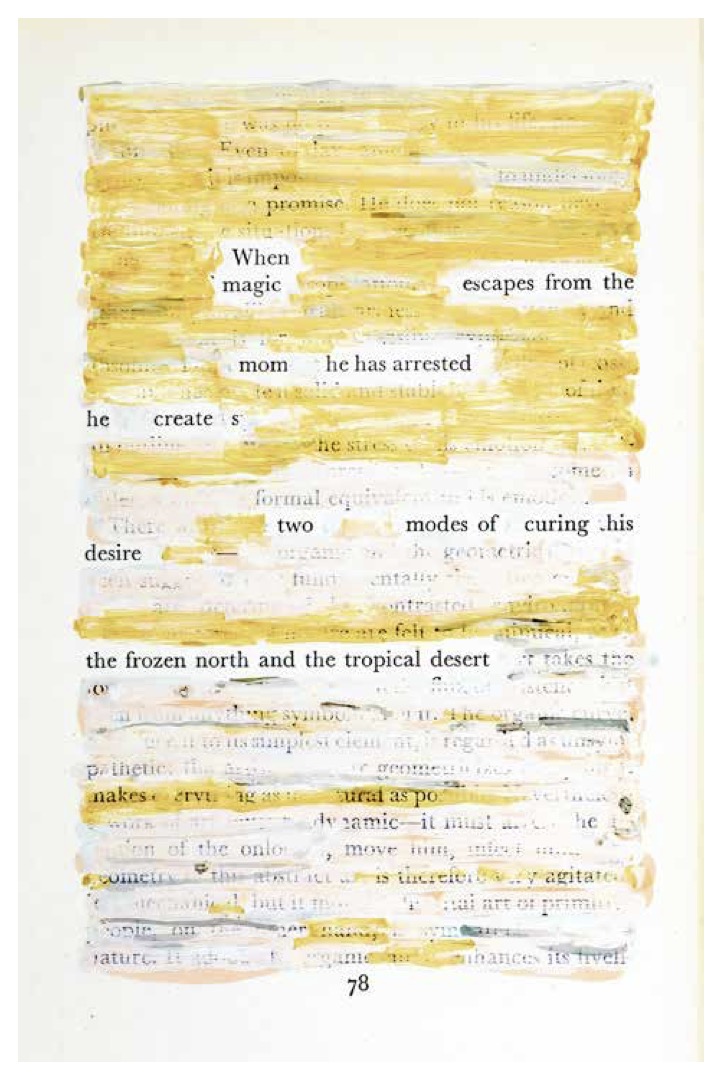

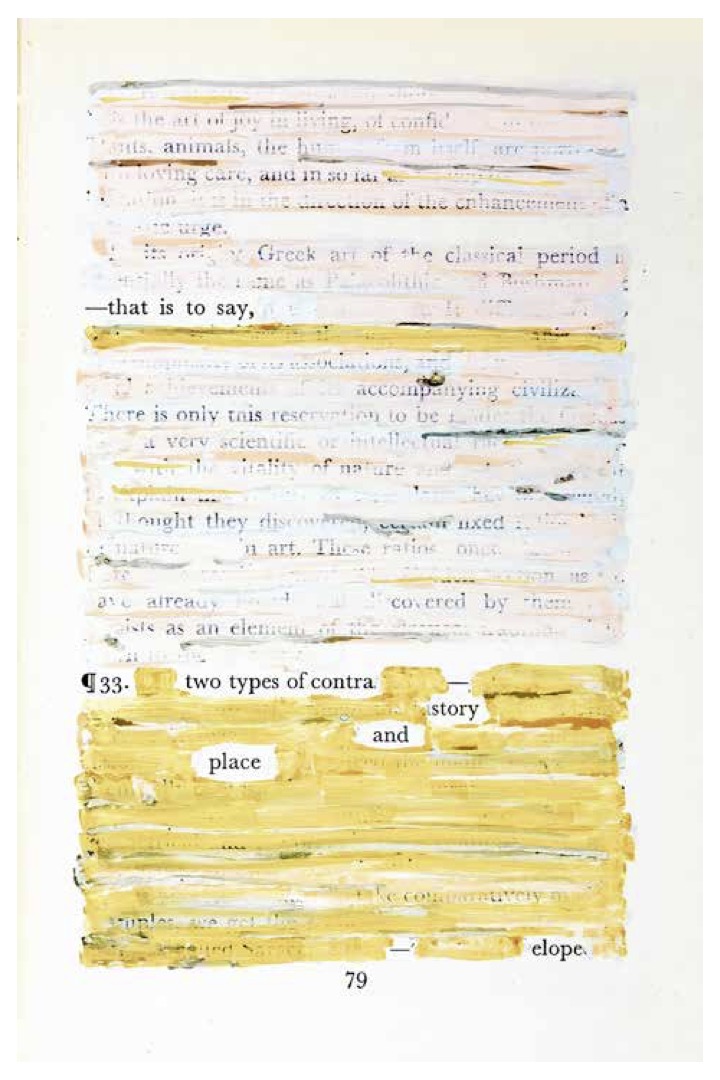

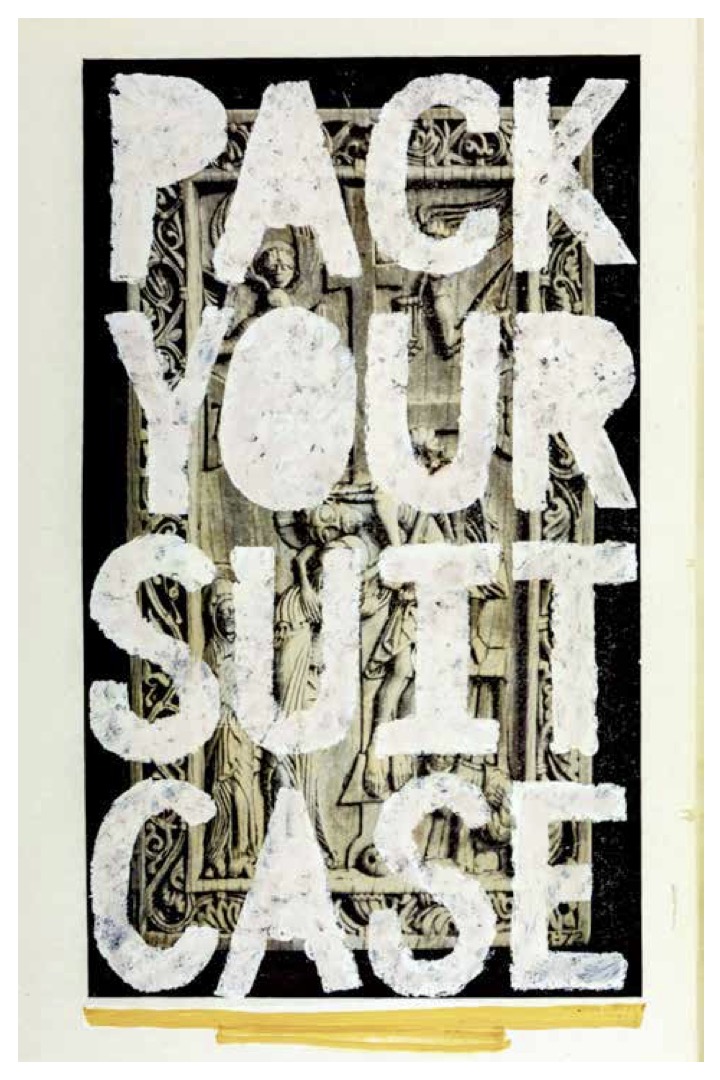

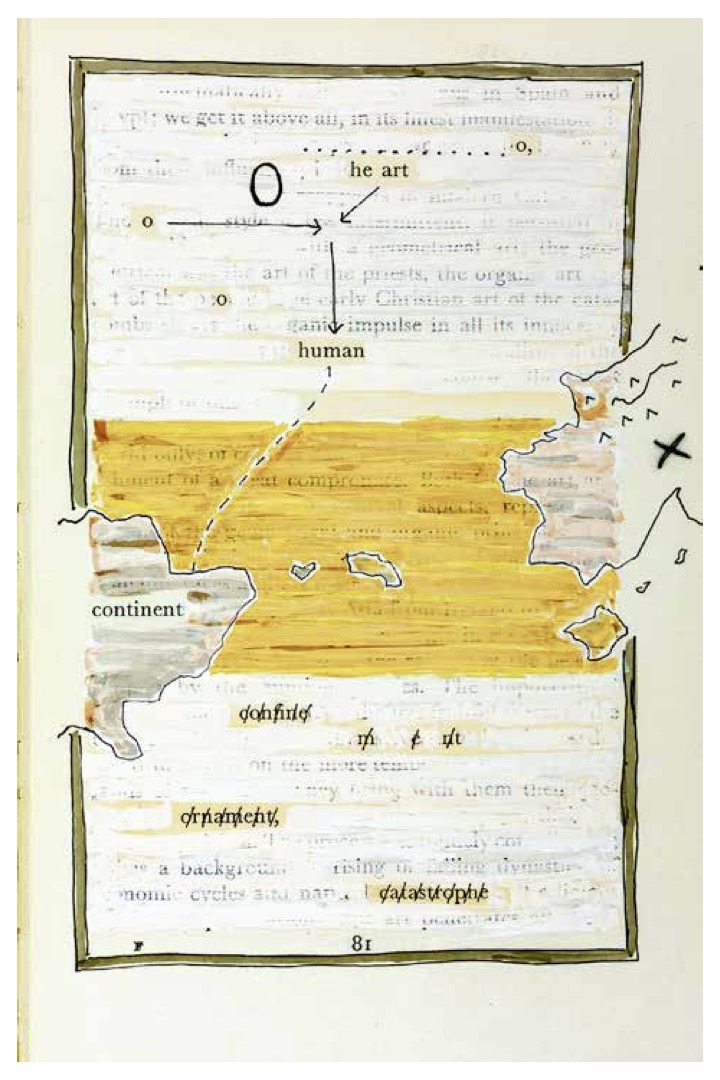

I had the pleasure of interviewing Jen Sperry Steinorth about her new book, Her Read, out any moment now from Texas Review Press. Her Read is an erasure project that Steinorth began in 2016, in the midst of the presidential election, and one she continued working on for the following four years. Her source text is Herbert Read’s The Meaning of Art, a survey/critique of western art, first published in London in 1931 (Faber & Faber, Ltd.). In “Her Apologia,” a kind of preface to Her Read, Steinorth writes, “Exactly zero womxn artists are included in early editions of The Meaning of Art. Not until 1951, twenty years following his first profession, does Barbara Hepworth become the only female artist Read admits.” And so Steinorth’s erasure becomes a kind of meditation on the absence of women, but, as the poet Eleanor Wilner writes in “Her Introduction,” it becomes much more than that:

. . . what begins in erasure transforms, as the book goes on, into a rich, layered graphic poem whose meanings emerge through skill in design and delight in pattern and texture—an artist’s and a builder’s and designer’s eye collaborating with a poet’s tongue, and a dancer’s knowledge of how expression begins in the body.

Stay tuned, too, for a special bonus video segment where we talk more about the relationship between pain and creation, and the ethics of erasure work.

AN: You have described Her Read as a graphic poem, a first-person female lyric that you “excavated” from its source text, Herbert Read’s The Meaning of Art—and I’m going to come back to the idea of excavation—but first, I wonder if you might speak to the popularity of Her Read, which has garnered a tremendous amount of attention in the months prior to its publication.

JSS: Oh, goodness. Well, firstly, thank you. In truth I have been quite surprised by this!

But you have me thinking about a phrase I’ve heard when describing feminist work born in the last few years, something along the lines of, that came out of the Me Too Movement, or that was born of the Me Too Movement, and they mean that it came up during the Trump Presidency, in the time of pussy hats and prosecution of dozens of high ranking men, some who were penalized, others who were not. But of course the use of the phrase Me Too to express solidarity with women articulating their abuse was begun by Tarana Burke a full decade before, and the issues are ancient. The disparity is woven into the fibers of our consciousness, into binary identities going all the way back. We have no history otherwise.

What I mean is, Me Too was just a symptom—a rash—a sudden disturbance that broke the skin of an already diseased body.

I think this work has garnered attention because the rage I was attempting to channel is not only my own. It was born out of my own experience, but that experience as shaped by our collective inheritance. It just so happens that in this moment, people are more attuned to listen.

Likewise, the marvelous proliferation of hybrid work by so many others in this moment has created space for my own work to be received.

But also, and I want to mention this for others who have a secret project they are shepherding, there is a way in which I may have talked this book into existence. I began it the summer of 2016 and was soon attached to it. I had it most anytime I left the house. If opportunity arose to talk about what I was making with a kindred spirit, I would. Sometimes I took the object out of my bag and showed them. It travelled with me to the Sewanee Writers Conference and Vermont Studio Center. Because it did not (then) seem to fit the molds, I was on a mission to discover who might be open to publishing the book—or excerpts—and how to package it. I let people know I was making a thing and listened to how they responded. These engagements deeply impacted not only the process of publication, but also the crafting of the work—techniques I used, arguments that played out. I also posted images of the work in progress on social media—Instagram and Facebook. It was all a way of breaking my own silences and, although I didn’t realize it at the time, it was a way of fueling the conversation that is this book.

AN: When you talk about our collective inheritance as women, and of “secret project[s],” I can’t help thinking about Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s The Madwoman in the Attic—their study of nineteenth century women writers and how feminine creativity so often correlates with madness and isolation. I think of how Bertha Mason Rochester’s rage literally burns the house down in Jane Eyre. I think of Dickinson alone in her room and lowering baskets of goodies to the children outside. I think of the very real importance of having a room of one’s own and also of the dangers of not having that “room.”

I’m not sure what my question is here—maybe it’s really a kind of three-dimensional one about space: about having the physical space—the room as in real, physical space, but also space on the page, and of course psychological space. You have talked before about the experience of being a ballerina, which requires a particular awareness of the body in space, and how the body inhabits space. How would you describe your relationship between space and creativity as you worked on Her Read?

JSS: This is such a rich question—you’ve sent my brain off to twelve different rooms to locate answers. And I love the context you give—the womxn you’ve brought into the conversation.

I immediately want to invite Judy Chicago into the space—one of the first womxn visual artists that I recall being both moored and unmoored by. Of course The Dinner Party asks us to consider what it means to have a PLACE—or a seat at the table. And I think of Louise Bourgeois who I discovered only recently—and who was not recognized for her prolific and profound work until she was around 70. Thankfully for us she went on producing art for nearly 30 more years.

So right away I am linking the question of space/place/room to the notion of recognition—the space womxn are given in the minds of others—regardless of gender. For a room of one’s own is absolutely essential but it’s not enough—one must not be confined to that room. I think it’s fair to say that womxn today have more room to create than ever before. Still, many womxn are denied access and even when they have it, claiming those spaces means sacrifice for womxn in ways it may not for men.

But even after a womxn has physical, mental, temporal space to create–after she has made sacrifices to do that work—has proclaimed her practice worthy of the support of friends, of family—there is still space in the minds of others to think of. As Audre Lorde explains it, there is the fact that, in breaking silence, in speaking for herself, a womxn (especially a Black, lesbian warrior poet, like Audre Lorde), may become the face of someone else’s fear.

I think of the size and shape of Dickinson’s poems versus Whitman’s. How many womxn get good at saying what they must with as few words as possible—not because they can’t go on—but because they know they have only a moment before the eyes glaze over.

I like that you ask about the body in space—which makes me think about the space inside the body. We need freedom within the body to negotiate spaces outside the body. But trauma is stored in the body and can cause it to lock—can make the body a prison.

The image of the madwoman in the attic absolutely resonates—gaslighting leads to madness. You also mention excavation as a metaphor for this work. I love this because I’m also a licensed builder and of course to begin you must first, literally, break ground. Drafting this book, I often had visions of womxn below ground—hands clawing through earth and stone—mouths filled with silt. There is a line midway through the book—But softly we hum feeling worser and worser slowly learning our mum’s genius is buried in the cellar. There is also a crudeness to the medium I used—the corrective fluid—which must be worked with quickly for it sets up fast. In fact, the liquid in the bottle thickens faster than it can be used, and when it thickens it creates a texture like mud. With this mud, I buried the source text in order to unearth the other.

And now I’m wondering what a psychologist would say about the difference between going mad in an attic and being buried alive? Certainly this work was helpful to my own mental health.

AN: And when you liken the corrective fluid to mud, it makes me think you are simultaneously excavating earth and creating earth/ground, so I’m just going to sit with that for a minute here—the idea of making earth to be able to unearth what is buried within it . . .

I’m fascinated with the fact that you’re a licensed builder. Can you talk a little bit about that and how it informs your poetry? As it happens, my parents ran a mechanical contracting company for years, so I was accustomed to growing up around tools and machines—and also what I would describe as an environment of hyper-masculinity and misogyny. I think a lot about the ways in which this informs my writing and subject matter, and I wonder if this is something you think about as well?

JSS: Ah, yes, I’ve been thinking about this a lot, actually! I was realizing that—though it’s true that there is a lot of misogyny in the construction world, in many ways it was much easier to negotiate than the misogyny I encountered in the literary/art world.

But then, unlike you, I married into a family construction business, so when I entered that world I was a grown-up, and a grown-up with a degree (in English—which was considered an asset—my art and communication skills filled a gap). My father-in-law welcomed my involvement. He didn’t always agree with my assessment of things, but I never felt dismissed because I was a woman. I sometimes had to prove myself with subcontractors, but honestly it wasn’t too hard—it was quickly evident I understood the principals at work. Plus, if they didn’t figure it out, they got fired (that happened once). Eventually, I became president of our company. I designed the buildings, managed contract negotiations and client correspondence and oversaw many aspects of construction particularly as it pertained to design. If potential clients had an issue working with a woman this way, they went a different route, but I never knew of a case where we lost a job because someone didn’t want to work with a woman. I’m not saying misogyny didn’t take a toll, but it was usually not too hard to identify and address. And it was clear our clients felt having a female professional integral to the team was an asset.

On the other hand, when I took a job at a prestigious art school, I began to experience more insidious misogyny. I’m still figuring out how to talk about this. In addition to misogyny, I’ve experienced disdain for the construction industry by folks in academia. I have experience in both construction and academia, but not many academics have experience in construction. Some of their ideas about construction are ridiculously romanticized—others are just oversimplified, and very few can imagine how the skills required to run a design-build construction firm may apply to the academy.

But time spent in design and construction has shaped my poetry in myriad ways. And time spent making things as a young girl! My mother was always making; she taught me to sew. I think a lot about structure, shape, pattern, proportion, relationship of parts. Relationship of parts is so critical—visually, intellectually. Hours and hours spent drafting house plans (ah, see! we DRAFT house plans, too!) has developed muscles that sense harmony of those elements almost intuitively. I think (hope!) that spills over into my writing. Even my first book—which was populated with both traditional and nontraditional forms, all created in Word doc—was very concerned with these architectural elements of structure and relationship.

AN: I’m curious about the mechanics of erasure as it relates to Her Read. How did you approach each page? I mean, you were working directly from an “original” document, so I imagine there was not much room for—I don’t want to say “error”—but it seems to me that once you start using the corrective fluid, you can’t exactly press “delete” the way you can when you’re drafting a more conventional poem, nor can you save different “versions.”

JSS: Oh yes, revision got tricky! But to be honest, the risk of irrevocably altering the book (the story!) appealed to me. I had to commit to my choices. Maybe forcing myself to take that risk (over and over) helped to free my then-constricted voice. One option for erasure artists is to photo-copy pages from the source (and experiment without consequence!) I resisted doing this as long as I could. Given the conceit, the female voice attempting to speak through the language of men talking about men—it felt appropriate that each choice I made would have consequences. On the other hand, in the beginning, I didn’t know what I was doing, where I was going and I didn’t want to back myself into a corner. I had to wade in and see what voice, what language emerged. So I moved very slow. I soon realized that I wasn’t “writing” a series of discrete poems, but one continuous poem. The syntactic line would frequently spill across multiple pages.

And right away I was struck by the high concentration of abstract, Latinate language. Not many concrete nouns. It was art criticism. Heady stuff. So when I entered a new page I’d scan for words that were promising and obscure the ones I could do without. I’d do this to several pages at a time, then circle back to eliminate more of the noise. This helped me to see the possibilities more clearly and ensure that what I was making would flow. But it took a while to lock down those first pages! And every time I made significant progress, I’d return to the beginning again—finesse the whole—stew on troublesome spots.

The first complete artifact took nearly four years—I finished shortly after we went into the 2020 lockdown. It wasn’t really a first draft—because it had passed through so many drafts along the way. And about half way through the book, as my images became more elaborate, I did start photocopying pages to plan things out. Sometimes those went through many drafts. I also used vellum over the illustrations to plan my alterations. And some of the vellum drawings I used to make stencils. The lamb in utero on page 147 was made this way.

Another revision strategy was excision. If pages weren’t working I could remove them or sew them shut. As with any writing, sometimes what wasn’t working was simply extraneous. This led to the use of needle, thread, scissors, scalpel—which then became drafting tools in their own right—especially in the last quarter of the book where the technique tends toward collage. In that section I surgically excise words from pages and rearrange them.

I should confess I did have a revisionist cheat. When conditions were just right, bits of dried Wite Out could be scratched off to recover the words beneath. It didn’t always work, and the potential mess was a risk, but I did make many small but significant revisions this way. Of course I didn’t remember what I had covered up, so I went online to find another copy of the book—a “key” to what was buried. Plus, I wanted a copy to read—I didn’t let myself read the original before I altered it. The first copies I purchased were the wrong edition. And then I might have become a bit obsessed hunting down copies. One I got for a few bucks (sight unseen) turned out to be a gorgeous leather bound edition! I think I ended up with fifteen copies of various editions

I remember thinking, in future years, I might want to make other versions of the book—as Tom Phillips had with A Humament. I didn’t expect to be back at it so soon. As I neared the end of the book—and the deadline to submit to my publisher—I realized too many pages felt messy. Like when you’re a kid writing in pencil, erasing every time you’ve made a mistake. I knew it would read better if I made the book again. So I did. It took about two months of around the clock work. Then, for reasons to tedious to go into, I ended up making a third copy—and that is the artifact which became the published book.

On my website, you can see how a few pages evolved across the three editions.

Incidentally, my friend Chad Pastotnik, a master bookbinder, letter press printer and artist, took the final book apart so I could properly photograph the pages. I planned to have it rebound, but it occurred to me that, as is, individual folios could be displayed in a gallery setting, alongside the earlier artifacts. Maybe folks might dig seeing the originals this way. In my dream world some fabulous curators say—hey!—YES—let’s make that happen!

AN: What are you working on now, and what are you reading?

Ah—this is a fun one—I’m finally reading again, so I’m excited to answer this question. And I’m returning to some back-burnered creative projects. There’s a swath of poems—not yet a manuscript—I can’t wait to return to. It’s something of a project book and I think it will have some visual elements as well. That is the hope! And there’s a series of lyric essays, I’ve been making notes toward for ages. Some explicitly address things I’ve already explored a bit in poetry—but use a marriage of personal experience and research to focus the investigation. Others meditate on craft. At this stage, I’m just making messes—researching, writing, stewing—early stages of several bits at once.

As to what I’m reading! I’m in the midst of Hunger: An Unnatural History by Sharman Apt Russell; The Body Keeps Score: Brain, Mind & Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel Van der Kolk; An Elegant Defense: The Extraordinary New Science of the Immune System by Matt Richtel; The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable by Amitav Ghosh. And I need to finish Sontag’s On Photography and Siri Hustvedt’s A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women. Oh! And I’m excited to dive into Thomas Lynch’s The Depositions: New & Selected Essays on Being and Ceasing to Be.

I’m also reading some gorgeous poetry including: Yona Harvey’s You Don’t Have To Go To Mars for Love; Sick by Jody Chan; Women in the Waiting Room by Kirun Kapur; The Body, An Essay, by Jenny Boully; Tortillera by Caridad Moro-Gronlier; Borderland Apocrypha by Anthony Cody and Alison Swan’s A Fine Canopy.

Jennifer Sperry Steinorth’s books include Her Read A Graphic Poem (2021) and A Wake with Nine Shades (2019), finalist for Foreword Reviews Best Poetry 2019, both from Texas Review Press. A poet, educator, interdisciplinary artist, and licensed builder, she has received grants from Vermont Studio Center, the Sewanee Writers Conference, Community of Writers, and the MFA for Writers at Warren Wilson College. Recent work has appeared in Black Warrior, Cincinnati Review, Michigan Quarterly, Missouri Review, Pleiades, Plume, Rhino, TriQuarterly and elsewhere. She teaches at Northwestern Michigan College and elsewhere. Connect at JenniferSperrySteinorth.com.