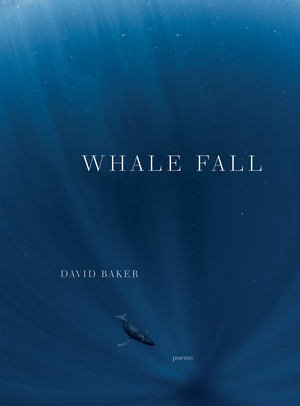

David Baker

Whale Fall.

2022. W.W. Norton & Company.

Hardcover, 99 pages. $26.95.

If in W.S. Merwin’s “For a Coming Extinction” the whales are on their way “to The End,” in David Baker’s “Whale Fall,” they’re already there. “One dies,” the seven-section, fifteen-page title poem begins, but the present tense demands that we watch the descent—watch, and count ourselves culpable. Merwin writes, “we who follow you invented forgiveness / We who forgive nothing,” and in Baker’s lines, we are truly unforgivable:

“March 31, 2016: 13 sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus)

beached themselves off the shallow coast at Tonning, Germany:

‘We may never know the exact cause,’ wrote Danny Groves.

Stomach contents: 43 feet of fishing net, 100 plastic bags,

golf balls, sweatpants, greenhouse glass sheeting, cigarette

butts, hypodermic needles, a plastic car engine cover, a bucket…”

The quoted lines come from articles on NationalGeographic.com, the Notes section of the book tells me, and it is a section sprawling and bibliographic in its account of the book’s dialogues with others. Baker’s poems cite newspaper articles, CERN Writing Guidelines on Nuclear Testing, field guides, and a host of other poets, including W.S. Merwin, Stanley Plumly, Jack Gilbert, and Charles Wright, to name just a few. Like the ecological interconnectedness described in the title poem and throughout, the book itself resembles the way one living thing persists and survives because of the work of other living beings: other poets, as they lived, wrote, and passed, sustain and nourish Baker’s work.

The title poem is its own section of the book, a poem in seven sections that at times feels like a hybrid genre, a lyric essay. Intensely lyrical moments invite us to see the phenomenon of a whale fall:

weight suspends;

a heavy thing in one world

floats like willow seed in a breeze

in this,

a moving vast through

that darkness, silent…

they don’t need

much else—oxygen, nor light—

the frilled shark

and fang-tooth, the spider crab,

the vampire squid, who strip the dead

down now

beyond bones…

Other moments in the poem communicate in the clinical language of “Wikipedia: marine snow is a variety of mostly organic matter, / including dead or dying animals, and plankton…also plant parts / and degrading plant material.” But as maximalist as the poem is in some ways, it maintains a tonal minimalism, and these kinds of Wikipedia moments assist. It is almost as if there can be no lyricizing the polluted contents of the bellies of dead whales, no metaphor to be made of that; we can only look directly at it, let language do its most basic function, which is to report what is.

Whale Fall fixates not just on death, but on the descent into death, from life into what it becomes—death as metamorphosis. As a book of ecopoetry, it could quickly slide into the merely catastrophic—because, these days, what else could it be?—but somehow, even as it elegizes, Baker’s Whale Fall also cultivates our attention to the marvelous. “Echolocation,” for instance, marvels at many creatures’—humans included—abilities to transgress distance in order to reach one another: “We are thin wires. FaceTime. Skype—” And of whales: “Researchers estimate the lowest frequency sounds of a whale— / Can travel / as far as 10,000 miles without losing their energy—” The poem weaves in references to Henryk Gorecki’s Third Symphony, also known as the Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, the speaker recalling, “When I heard it the first time, I had to pull my truck off the highway—” Music, in this poem, becomes the common ground, the middle distance between the locating sounds of animals like whales and hummingbirds and the language of humans. Like echolocation, music “Cuts through the black abyss,” is made of “Waves,” which, “in both directions along the string,” reinforce and cancel each other “to form a responding harmonic—” (the italics are always Baker’s to indicate quoted text).

One of the things I admire most about the collection is Baker’s way of bringing together many topics that feel unwritable in their enormity, too grand to permit entrance—and yet he finds entrance after entrance. What I mean is, this is a book of pandemic ecopoetry. “In our year of distances” these poems emerge. For many writers (myself included), Covid-19 may feel too near, too ever-present, to represent truthfully yet, but Baker imposes enough lyrical distance to see it with clarity. The earliest poems in the book place us in time. From “Nineteen Spikes”: “Then the storm came. It raked our world with terrible teeth / …Wash your doorknob. Your hands. Triage your mail. / I had a nightmare I was living my present life—” The poem superimposes the event of living with coronavirus upon another event from 2013, when an Ohio farmer died trapped in his grain bin. This line startles, echoing the image of a whale fall at the heart of the book: “It took his body hours to work down through the corn—” Juxtaposed, the two events, especially in the context of this book, allow us to think of the pandemic, perhaps, as the human version of a whale fall, which likewise can take years to be fully complete.

“What you call / a thing is seldom what it is,” Baker writes in “Mullein.” That may be true, but I think Baker is right more often than not in this gorgeous, mesmerizing eleventh collection.