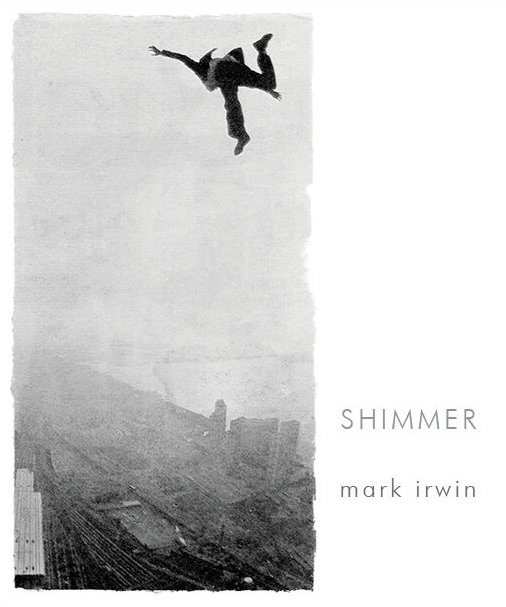

Mark Irwin’s Shimmer

Shimmer, the winner of the 2018 Phillip Levine Prize for Poetry, is Mark Irwin’s tenth volume of poetry, and follows 2017’s A Passion According to Green, and a selected volume from 2015, American Urn. Readers can comb through American Urn, and witness a fascinating evolution of a poet across half a dozen volumes. One of Irwin’s biggest stylistic leaps occurred between Tall If and Large White House Speaking—Irwin has always been a lyricist with an unfailing ear, yet often moved from lyric into fable effortlessly. Large White House Speaking, more than any other volume before it, often offered a fabulist mode, in which Irwin knocked the reader off-balance with a concept that was impossible, yet was nonetheless breathed to life by the poem. It was also a book in which the reader witnessed more of Irwin’s personal side, as in the poem “Rider,” in which the speaker carried his elderly mother across a hospital room, and when she sang, nonsensically, “Giddyup, / Giddyup,” the speaker “nodded my head, snorted, then put a pencil / in my mouth, as bit, and cantered about the room / till I was out of breath…” A Passion had a number of inventive and dreamy speculative poems, and in the book Irwin managed to bridge the personal and the fabulist, as in the moving and beautiful “Zoo,” in which the speaker and his mother, while at the zoo, begin to run toward youth, “and the skyline of a city, its fossil, while animals, shrieking, stampede past us, and mother calls out their names, / zebra, buffalo, gazelle, ever so clearly, then enters into shadow with them, that diorama we call memory.”

There are poems in Shimmer that seem in dialogue with poems in A Passion, or perhaps feel like continuations. For example, “Welcome” escorts the reader into a model home, where the “you” awakens sleeping people, “smiling like they’ve known you all / these years, and then they dress and leave while you / stay and become that couple…”, a poem that hearkens back to “Open House.” in A Passion, where a speaker encounters, within an open house, a model of that house, and though the poem veers to a different ending, the tone and conceptual strangeness of the poems make them feel like kin. “Toward Where We Are” is a brief, beautiful lyric poem, another that wouldn’t feel out of place in A Passion, which has a number of these little windows that open into radiance and wonder. And yet as much as I loved A Passion, I think Shimmer is another leap for Irwin, in both content and in style. First, though Irwin has given us ars poeticas before, the book is framed by poems that are almost letters from him to us. “What a great responsibility to think of things that no longer exist,” he writes in the first poem, and goes on to name and describe buildings, animals, and people. It’s a proem of sorts, a guide to the book, and functions in much the same way as the book’s three epigraphs. “What a Great Responsibility” and the final poem, “And Now,” provide a framework for the book, as the latter is a commentary on Irwin’s journey as an artist: “…traveling toward the page, I was learning / how to make light, to make things visible,” and then adds what I’ve begun calling—forgive me—Irwinian details, precise images delivered within phrases that often feature an amplified soundscape—assonance, consonance, internal rhyme, etc. “…hair bound by a tortoise shell clip, / a wedding band whose thousand scratches each comprise a lost orbit, / a fascicle of red leaves, still sun-struck, talking of the charcoal trees, light / leaping form a trout’s side…”

Second, alongside the fable and fabulist modes, this collection delves deeper into the present world. Way back in 2007—which sometimes feels like a lifetime ago!—Irwin included a poem in Tall If that declared “the panoply // of reality shows has begun to exorcise / the very notion of reality…”—which, perhaps, might partly explain the election of our first reality show president—but this collection has the poet witnessing melting glaciers, and extinct animals, and ISIS, has him exploring what technology can do to our minds and souls (“May kids from the concrete metropolis find those deer, / their gaze a tissue of fear fetched far from video camera / or computer chip till the laptop becomes sheer altar, / for blessed are those who can tap a letter’s key and know its curved weight…”), has him noting “dollars and smart phones,” and grieving over a YouTube video of a horse being dragged with a cable to be slaughtered. How does Irwin manage to write an inventive poem when contemporary American poetry is so cluttered with the present moment, with our technological reach, and with our ecological impact? The last poem, I quoted, “Emaciated white horse, still alive, dragged with a winch cable to be slaughtered,” is a fine example. From the literal moment of a speaker watching the video, the poem turns to the figurative: “Stop, I said, till the horse / becomes a house for us all. We live inside the hide / of that archival tent the wind still bellows / wild.” The speaker turns to a magic word to make it all disappear, then turns toward a surprising explication—almost a blessing inside an insight about language itself: “Sometimes / you need to forget the words // before you can know the feeling. —To push the shovel’s tang / polished from each shove / into blue soil. To bury // the horse in earth while the galloping white space between words never stops.”

Third: I mentioned that the poems feel more enmeshed with the present world in which we live—but not just in the ways they wrestle and sing the present landscape and technologies. I think this book, more than any of its predecessors, offers a speaker who is more vulnerable. This book is dedicated to the memory of Mary Lou Irwin, Mark’s mother, and it hit me on my second or third read—she also passes away in this book. In one of the book’s first poems, “Purple,” his mother is dying, and tells the speaker that she dreamed him being born again—what a haunting beginning to a poem!—and the speaker then confides to us how she smiled, “how happy she was to have this second time”—but after she died, the speaker dreamt this dream as well, one that leads to a dream-revelation shared by the speaker and his mother. “Two Panels” walks us through a variety of the speaker’s memories, across time, across the world, from his infancy to dancing with her to “Mack the Knife,” to sitting with his mother, who is in a wheelchair, in assisted living—until she could no longer speak, and they passed notes back and forth, until the notes meant nothing, and so they passed colors back and forth. “Here” meditates upon its title word, which takes the poem through the speaker’s grade school, as roll was called, to these lines: “What it meant then / seems so much less than now, here with Mom / at the nursing home, here with the surgeon cutting the melanoma / from my cheek…” She is not a presence in every poem, and the poems that do grapple with her dying are formally, structurally, and tonally distinct from each other. “Two Panels,” for example, is delivered in a series of sentence fragments, and jump-cuts from memory to memory, while the sentences that form “Human Lag” are tied to each other by anaphora. It is no small feat to grieve another’s life—especially that of one’s parent. And to overcome that grief, or just to work through those feelings, and to write a poem about that parent, that manages to surprise the reader, and to earn the sentiment that will inevitably douse the lines? It’s an almost impossible task. And yet, the poems that mourn her and celebrate her are as inventive as the others, and of course, just as poignant.

The range of some of Irwin’s poems is astonishing. “Eclipse” finds the speaker eating tomato sandwiches with his sister when an eclipse happens. Right after the speaker and his sister glimpse Venus, “along with two minutes of just-thrown stars,” they become, in their astonishment, bodiless. The poem skips a stone back into the speaker’s memory just then, and he recalls seeing his mother naked. How does the poem manage the transition? The memory is housed within the speaker’s body, of course, but this memory is both analogous to witnessing an eclipse—a singular event that elicits a strong reaction from the witness—but also a kind of antonym to being bodiless—the speaker charged with shame “for where I’d been but could never return,” much like the Voyager I, which is where the poem leaps next, hauling the precision machinery of which it’s made as well as a Golden Record, a kind of shorthand of what it means to be human. “Eclipse” then sets up an observation several lines later—“Sometimes it’s scary / what a word will summon, its black stripes chasing after…” by giving us Wile E. Coyote, who attempts to catch the Roadrunner with a tiger trap—but finds a tiger inside instead. The poem keeps us from knowing what a doctor told the speaker in the next line, but he confides that he longed for a new word, “something made / out of No, Please, and Yes.” Fifty years go by in a snap in “Domain”—the line breaks, in fact, after fifty. Yet it’s not only the range that moves me, but the depths, and that Irwin pairs this range with such precise imagery—and that the structure of his poems, and the way they unfold and pivot and move, are almost always unique. For every poem that stays in the arena it creates, like “Little Transfiguration Suite,” which charts a single transcendent moment outside of a pharmacy, or “Sarah,” in which the speaker’s friend, a surgeon, lost his daughter—he was one of the surgeons who operated on her!–there is a fabulist poem with an impossible idea, or a poem that moves in an associational fashion, that leaps valence to valence, like “Threshold” or “Life is a Red Car” or “Sunlight.”

Irwin’s poems love the light, and language itself. And though I’m fascinated—and delighted—by how he opens up and makes room for joy and wonder, as in the one-sentence “How Magic”—and what a sentence it is!—I’m also often moved into reflection by Irwin’s observations on language itself, which come through in so many poems. For example, “Herald” demonstrates how grief changes the words we speak—how it charges them, holds them up in a different light, and ridicules us for how words like now can alchemize, or transfigure. “How odd to speak / of you now, a name glittering off the tongue / into air. Better to speak orphaned words / not clothed in a suit of grammar than to keep foraging / for the dead while the memory fades and words / get stranger, like catkins blown gold…” (As a side note, look at those line breaks! The silence after “speak;” how the second break enacts that word traveling into the air; the juxtaposition of “orphaned words” and the empty space that follows) The after-effects can be like a second birth in fact: “…sometimes the wooden / door opens to deer, the deer toward woods, and the woods / toward lumber that becomes a house again where you stand…” “Herald” shows us this circularity in that quoted sentence, even as a speaker struggles with loss, and the guilt of still living, even feeling this guilt while putting on sunscreen. There are also a number of poems that begin with a single word–”Who,” “Maybe,” “And,” and “Here,” for example–and pivot from that word, sometimes interrogating our contemporary usage, sometimes investigating its etymology, sometimes unspooling a fable or brief lyric through the world, through dreams or memory. And then there are also concepts, sights, and sounds that are beyond language, like the mewling sounds that the speaker and his dying mother spoke to each other, described as “much older than language,” or the stars of the Milky Way, “a first language we can’t touch.” Perhaps this examination is at its most poignant in “What did you do today? How long will it last? Will you remember?” which begins “Time, trying to name what has no name. Your Mom’s / death. Where you were when it happened.” The poem charts the difficulty of affixing words to the present moment, the now, much as “Herald” did, but notes “The rope of language and all its fraying strings,” the few words an unnamed “you” said with the “entire force of your body,” and finally, a return to a childhood house “no longer home / and be haunted by that word”—an especially bittersweet return, following the death of the mother, and made more forceful by the juxtaposition of Rome and its monuments, in the second and third lines of the poem.

In other words, this is a book that charts and explores the language it uses, even as the poet pushpins what’s beyond the language, or shows us where it simply doesn’t suffice—even while grieving, toasting, and loving the people around him, alongside this world. I read through Shimmer a number of times, and the poems kept moving me—and surprising me. This isn’t just a book for readers who love language, it’s also for poets who wonder, though they may never have voiced it: “How to gather / it all up? Or where to go when it’s gone? There’s always the forest / at midnight, where we would have in the past. It waits there untended…”

For more on Mark Irwin, you can visit his Poetry Foundation page , among many others.

Shimmer

Mark Irwin

Anhinga Press

January 2020