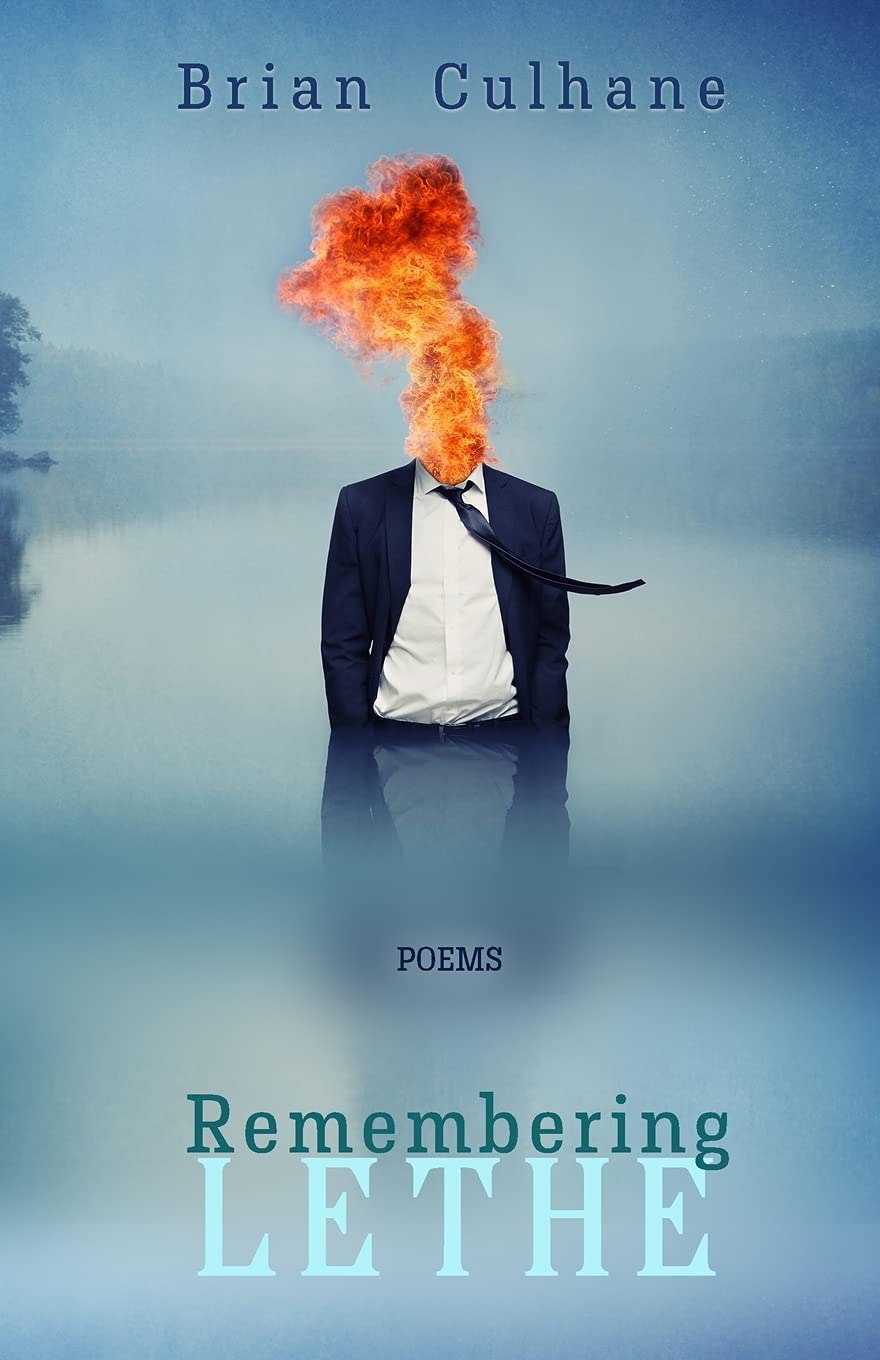

Brian Culhane

Remembering Lethe

2021. Able Muse Press.

Paperback, 66 pages.

Reviewed by Chelsea Wagenaar

Brian Culhane’s Remembering Lethe is remarkably, refreshingly cohesive. The assembly of poems speak back and forward throughout the collection, echoing and recalling each other in a way that enacts the cyclical nature of remembering and forgetting at issue in many of the poems. This collection rewards the thoughtful reader who wants to make connections; they’re there, and the poems yield to scrutiny. Remembering Lethe is elegiac, wise, and richly in dialogue with both its more immediate and classical ancestors.

“The Essay” is second in the book, acting as an invocation for the many poems to follow that also take up the subjects of teaching, writing, and learning. Throughout the collection, teaching and learning serve as antidotes to Lethean oblivion, a way of resisting it. Can knowledge save us from oblivion? Can it stave it off, or even open oblivion up to us before we must enter it? In “The Essay,” we don’t know what assignment the students have received, only that “theirs is such a dark and rich theme” that their pages may result in something akin to the chaos and crypt of Kafka’s diaries—“with self-portraits, / Wraiths, and ominous clocks.” I suspect that the implied theme of the students’ essays requires a great deal of self-searching, of interiority:

I want each to follow the footsteps of the psychopomp

And find the Gates of Horn where so many have stood before.

The task is not just difficult, as all essay-writing is; there’s something here particularly to be dreaded, a feeling of not wanting to round the corner or open the closet and see what lurks there, as the students’ scribbling is “an uneasy rowing” and “the dread of conclusions scrunches their shoulders.” In this latter phrase, “the dread of conclusions,” we hear one of the book’s primary tensions: the dread of making conclusions, of finding unwelcome or terrifying truth, and the dread of becoming concluded oneself, consigned to oblivion, the kind of forgetfulness that precludes the possibility of truth.

“Longhand” feels like a sibling to “The Essay,” written with an opening stanza of imperatives instructing the reader in writing longhand: “Here, try it right now. Put pen to unlined paper.” Unlined paper—the admonition is to leave all charted courses behind, to descend into the chaos of the mind, recalling Kafka’s diaries again. But in this poem it’s not Kafka’s diaries on the witness stand; it’s Thoreau’s journal under scrutiny. Culhane writes of an ant battle Thoreau observed on a windowsill and recorded in his journal, two red ants defeated by a larger black ant, which led him to pen a strangely prophetic statement that would seem to anticipate the Civil War, and his own death before its conclusion: “‘I never learned what party was victorious, nor / The cause of the war.’” So why longhand? This is not a mere quaint nostalgia at work; it’s life and death, as “the longhand of thought / Always must contend with the world at hand.” As the ants contended with each other, as Thoreau contended with the struggle to observe and make sense of what he saw, so Culhane urges the reader to leave behind the safety of charted territory and cross into “the abyss / Between words.”

The abyss between words calls to mind “Standing by a Coppice Gate, Reading ‘The Darkling Thrush.’” In this dialogue with Thomas Hardy’s poem, Culhane admits the distance between the impression Hardy’s poem originally left him with—imprecise as it turned out to be—and the correction of the dictionary.

Much later I learned

Coppice was not another word for copper,

Nor bine evergreen exactly. A fire burned

Through mists: meanings shape-shifted

Until the dictionary won out and the gate

Led to a thicket, bine to a twining plant.

Culhane’s concluding stanzas remind me of one of Richard Hugo’s aphorisms in “The Triggering Town,” which I’ll paraphrase here. Hugo says that in a poem, inevitably, either truth will bend to music, or music will bend to truth. The latter, if music bends to truth, may result in poems of foregone conclusion, dead language, tired revelations. In such an instance, the poet has strong-armed an idea into being rather than taken pen to unlined paper. Culhane’s “Standing by a Coppice Gate” celebrates the freedom of doing the opposite: prizing music over truth, for the sake of joy, for the sake of another truth. Though he was inexact in his understanding of coppice, bine, even thrush, and though “Nothing can wholly unlearn past ignorance,”

I read on,

Half right, half wrong. Again, I feel a boy’s joy

That is two parts darkness, one part song.

It’s a stanza, and a poem, to be envied, no less because of the musicality it both celebrates and emulates.

Is oblivion itself a kind of knowledge? It’s unanswerable, of course, because to know oblivion would be a contradiction in terms. “Etiology,” toward the end of Remembering Lethe, takes up this question. The poem opens in a doctor’s office. “I showed him my shaking shaking hand / And the doctor, a specialist in shaking, / Shook his head, No, which I believed / Meant perhaps…” and the rest of the poem proceeds from that “perhaps.” The doctor never speaks, except in the speaker’s imagination, and we never return to the doctor, moving instead away from the etiology of the shaking hand and toward the etiology of the speaker’s ignorance of his own condition, his imagination of those grander causes. Here read the final lines of the poem:

…you may one day

Live in a house in a village and raise a garden,

The flowers of which will rise and fall with

The seasons, and you may find peace there,

When knowledge comes calling at the last.

That “the” before “last,” coupled with its place as the poem’s last words suggest that we aren’t speaking of a general moment of revelation in life; we imagine death as synonymous with knowledge, an oblivion not to be dreaded, perhaps, but hoped for, the ultimate mending.