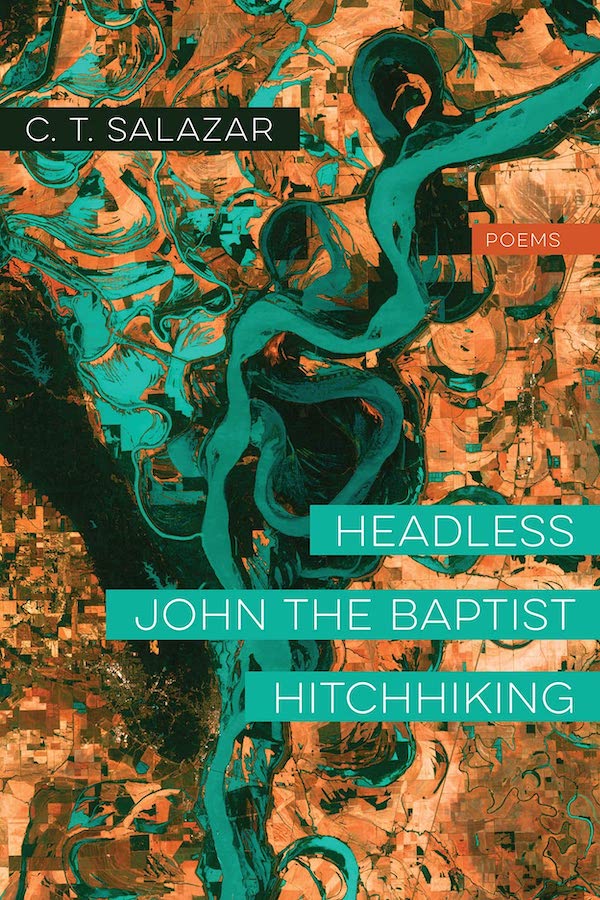

review of Headless John the Baptist Hitchhiking by C.T. Salazar. Acre Books.

One of the great, disorienting pleasures of C.T. Salazar’s first full-length collection of poems is how little level ground it contains. Take “Self-Portrait as Headless John the Baptist Hitchhiking” (the poem that lends the book its title). In fewer than 20 lines, Salazar spirits us to at least three locations, the most elaborate an apartment containing a bed and an irregular polygon of hardwood on which two strangers dance. Of course, there must be more: a kitchen, a bath, a floor that runs from wall to wall. Everything inessential, though, falls away. Elsewhere in the poem, Salazar lays down just enough tar to change a tire on or to hitchhike from. Likewise, he outlines just enough yard for beetles to scuttle around, “pieces of a star trying to reassemble itself.” And such small landing spots–sparse, partial settings–are the norm in this book.

Perhaps it is because their settings are so wonderfully patchy that these poems move as acrobatically as they do. Or perhaps it is his knack for leaping that motivates Salazar’s tendency to define no more than the islands (pop-up places or spots of time) that his verses need, deliberately putting space between them so that he has the room to exercise his talent. Whatever the trajectory of cause and effect at work, in Headless John the Baptist Hitchhiking form (the leaping between locations in time and space) and theme (a belonging that builds under your feet and then drops off) conspire.

Indeed, this book includes many strongholds even as its sure places are not contiguous. Between them floods and rivers run. Above them loom outsized skies. On that water and ether, admittedly, float little bits of terra firma: an ark, a “star-filled star- / field.” Even so, Salazar’s book does not provide its readers with a map of its setting. And what it delivers by way of narrative and image does not resolve into a forthright photo essay. Instead, this book arranges–by the dictates of art rather than the dictates of order–undated Polaroids and spare, sometimes cryptic, postcards mailed from places you wouldn’t expect.

Don’t mistake me: Salazar’s imagery isn’t a hodgepodge. Between mementoes and souvenirs and details snipped from lost maps, motifs do emerge: telltale wounds and barns, scents and tongues. For example, in the collection’s second poem, Salazar writes,

[…] All the bones at the

bottom of the Rio Grande I’ve inherited the way my mother inherited

my grandmother’s teapots. I’ve seen two shatter.

Those teapots return many pages later. So does the grandmother. In “Sonnet River,” the speaker first promises to

[…] shake all the dust

from the hymnals to name each floating god

-speck after our grandmothers.”

Then, on the heels of that promise, Salazar asks, “What’s the heart if not / a teapot of blood carried in the chest?” I love the teapots’ reappearance; I love how they remain breakable and affiliated with a matrilineal gift (or encumbrance). But I also love the teapots’ transfiguration: how they are no longer the kin of bones because these vessels have turned into hearts. And that a ceramic object might shatter and then come back, sanguine, an engine–the heart–is another of the truths Salazar insists upon.

While, then, this volume of poems argues that the spots where we feel sure (of who we are, of where we came from, of what destination we’re hitchhiking toward) are widely scattered and mostly small, it also argues for bizarre and holy resusitations. A diamond “lost at the edge / of the woods while chopping firewood” comes back after many years. “[L]ittle lost diamond son,” the poet writes, “there you’ll be.” And even as “Noah’s Nameless Wife Takes Inventory,” the columns of her list steady in form but her focus sliding away from the task of listing, she also defies history, turning up in a poem titled “Noah’s Nameless Wife Sees a Golden Bust of Joan of Arc.” It begins:

Sometimes we lose a woman to water

+

sometimes to fire.

But the poem’s unspoken premise is that those we lose to water and fire (or whatever other element) we do not lose–not really.

Such slightly skew recurrences, then–whether of object or place or person–embody the belief that the lost are more mislaid than irrecoverable, more dormant than extinct. Salazar, however, goes beyond voicing this belief. Headless John the Baptist Hitchhiking also makes the reader an accessory to its reclamations. Consequently, reading this book means re-reading. It means following the thread, by way of a homophone, that connects “Noah’s Nameless Wife,” the mistress of an ark, to Joan of Arc, the French saint with an Anglicized name. It means meeting Salazar’s father in an ICU and hearing him described as “a bear / they cannot handle,” as “a handful,” as “an arkful,” and then looking for him in the inventory of Noah’s boat, fifty pages later.

Simply put, this book trains its reader to do what its writer does: it teaches us to leap. The poet gives us practice at hopscotching between sturdy landings, from the small outposts of home and belonging to the patches of certain ground where those who suffered and strived before us found their footing and dropped a pin.

Salazar cannot, of course, hand us a map of the strongholds we are looking for. He cannot tell us where these places of knowing and being known, of feeling sure, will be for us, let alone give us directions to them. Nor can he tell us the names of those places and moments. Instead, he does something more generous. He gives us a vulnerable, venerable example. No wonder his collection ends with a diptych titled “Poem with Three Names of God + A Promise to Myself.” After all, the whole of Headless John the Baptist Hitchhiking sings with sidelong, reluctant prayers and with the covenants of naming and renaming.

For instance, in a verse that begins with a speaker who wants to christen himself “Hallelujah,” Salazar announces,

[…] Tonight, I want to rename

mountains not after the people who climbed them

but their reasons why. I could say, I wanted to quit

but I was halfway up Mount I Could Never Forgive Myself

If I Gave Up Now. Monarch butterflies in their migration

still curve around a mountain flattened hundreds

of centuries ago. If I could name them anything,

I’d call them the ideal shape of faith.

Of course, this mountain, from which climbers will whoop the speaker’s chosen name, Hallelujah, “to clouds they’d finally seen the top of,” might be the same heap of granite that was “flattened hundreds / of centuries ago.” Even so, Salazar turns “Mount I Could Never Forgive Myself / If I Gave Up Now” into a stronghold. Flattened or soaring, after all, it is solid enough for butterflies to plot their routes around. And, flattened or soaring, its halfway point is still a fastness, the home of the moment that one resolves not to give up, the spot where one chooses to be the self they can forgive. Maybe it is tempting to wish for the poet to send us the coordinates to this climb, but Salazar doesn’t. He doesn’t presume to rename the mountains or molehills we readers scale, either. He stops at “want[ing] to rename them.” He sticks to the conditional: “if I could name.” For me, his wish is enough. And his example–of leaping between surenesses, of reviving the lost, of changing names, and constructing “churches / […] to praise little things that deserve / more than their few seconds of existence”–is more than I could ask.